‘Fitbits’ for fish

A look into the effects of temperature and exploitation on fish activity

A recent technical leap in the watch industry has led to the popularity of “Fitbits” allowing us humans to constantly track our day-to-day activities through metrics such as steps. It may come as a surprise to many, but this technology is also available for our underwater friends in the form of acoustic accelerometers. These are miniature transmitters (weighing a mere 12.2 grams) that are implanted into fish and record the average number of tail movements every 50 – 70 seconds, returning this data as acceleration (m / s2) values to close-by underwater receivers via sound waves. With this equipment, scientists can now assess the effects of factors like water temperature and habitat type on the activity of marine vertebrates.

A caught red roman on its way to get a “Fitbit”. Photo by Mike Skeeles | © Acoustic Tracking Array Platform.

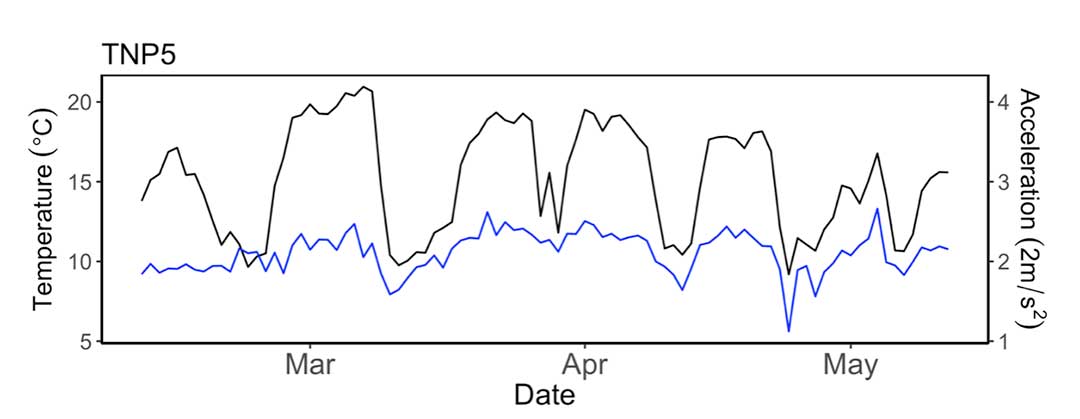

Average daily water temperature (black line) and acceleration (blue line) of an individual fish over the three-month experimental period. Note how temperature appears to drive activity.

A recent collaborative effort between the South African Fisheries Ecology Research Laboratory (SAFER lab) of Rhodes University, African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme (ACEP), Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP) of the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB) and the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) saw the successful use of this technology for an MSc research project by Mike Skeeles. The project looked at using acoustic accelerometers to assess the wild activity of exploited and protected populations of a highly resident South African sparid, the red roman (Chrysoblephus laticeps), in response to periods of temperature variability off the south-east coastline of South Africa. The ultimate goal was to explore whether over-fishing influences the activity and behaviour of this important line-fish species at different temperatures.

Infographic of this study that assessed whether over-fishing influences the activity and behaviour of this important line-fish species across different temperatures using acoustic accelerometry. Artwork by Mike Skeeles | © Acoustic Tracking Array Platform

Thirteen receivers, the underwater ears that listen and store the acceleration data from the tagged fish nearby, were deployed in the exploited Port Elizabeth (PE) and pristine Tsitsikamma National Park (TNP; South Africa’s oldest marine protected area) areas. The receivers formed a square-shaped array providing a coverage area of 400 x 400 meters, a relatively small space in comparison to the vast ocean. Ten red roman from each site were then caught within the respective array and implanted with their very own accelerometer tag or “Fitbit”. Fish were released back into the array where their activity was recorded (we hoped) for three summer months when temperature variability is highest. The temperature within each array was also recorded so that we could link this environmental factor with each fish’s activity.

Mike Skeeles with a red roman in Tsitsikamma National Park.

Waiting three months hoping each fish stayed within such a small area of the open ocean was painstakingly stressful. Nonetheless, after time was up our team SCUBA-dived the receivers out, a task that can be time-consuming along this coast as conditions are very rarely favourable. The long wait was well worth the life-reducing, wrinkle-baring stress, as we managed to capture close to 500000 acceleration estimates in PE and 400000 in TNP. Further, temperature variability at both sites was immense, with temperatures often fluctuating between 9 and 20 °C within a day. This detailed data allowed us to really assess and compare the natural-state activity of both populations across different temperatures.

Mike Skeeles with a receiver in Port Elizabeth.

Our results indicated that, firstly, the activity of these fish is highly driven by temperature. After comparing both population’s response, the exploited fish appear to have a significantly reduced level of activity towards sub-optimal temperatures. Individual fish from the protected population also showed greater diversity in their activity response with 40 % expressing higher levels of activity towards temperature extremes. These results could be related to the effects of passive-fishing removing the most active and bold fish from the exploited population. If so, in light of temperature variability predicted to increase with climate change, it is a concern that the exploited fish appear to be more sensitive and express less diversity at temperature extremes as this could lead to a reduction in their resilience against future change.

Detailed results and information about this study will be available shortly in the future. But for now, the take-home message of this post is the importance of collaborative efforts. In a developing nation such as South Africa, a study like this would never be possible without a widespread team. Thus, I am incredibly grateful for all the help and support given by the SAFER lab, ACEP, ATAP and OTN and look forward to sharing these results which (*hint alert*) provide major evidence for the importance of protective management.