Finding, sampling, and tagging scalloped hammerheads offshore, easy…right?

Imagine yourself in the middle of the ocean scanning out towards the horizon. There is nothing all around you – just the deep orange and golden hues of the setting sun, the rich azure water, and you. If we decided to put on a mask and snorkel and jump into the water, we would see a one of the most beautiful and healthy coral reef systems in the North Atlantic just 120 km off the southeastern coast of Texas!

View of the water’s surface at the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. A remote and isolated reef system approximately 120 km offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo © Brett Sweezey

The Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary is a complex network of deep-water coral reefs that attract many commercially and recreationally important fish which spawn or forage at these banks despite being relatively isolated from other reefs in the region. One of my target species that utilises the unique habitat at the Flower Garden Banks, which is believed to be associated with foraging and mating behaviours, is the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini). For my research, I plan to link the movement behaviours of these species with their trophic ecology to estimate their foraging behaviours at the sanctuary.

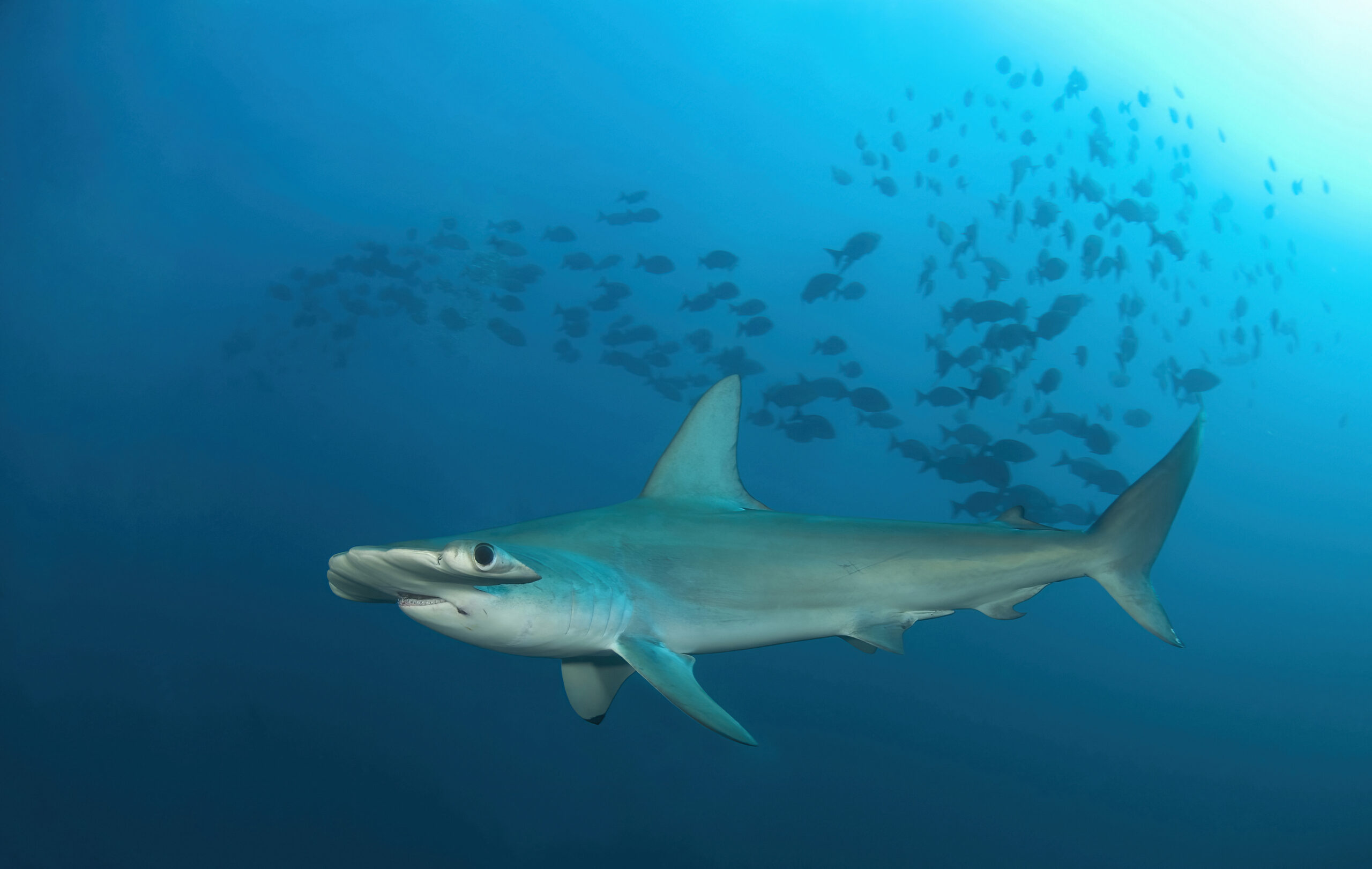

A scalloped hammerhead shark swimming by a photographer at the Flower Garden Banks. Solitary individuals can be found throughout the sanctuary year-round which are rare but exciting events! Photo © Jesse Cancelmo

Now only if I could find any scalloped hammerheads! Over the last year, this project has had to overcome many unforeseen hurdles (foul weather, equipment malfunctions, and the lack of finding hammerheads!). However, as I start to wrap up my second field season, I have YET to personally capture and tag a scalloped hammerhead. I thought my luck was starting to change a few months ago when I finally saw one appear at the surface, but it disappeared before we could catch it! I knew that it would be difficult to find these individuals, but I did not know there was a possibility I could go almost two years without seeing a single individual. This was upsetting because not only did it feel like my project was failing, but I thought I was doing something wrong as a researcher. However, fieldwork almost never goes according to plan, and I had to come up with an alternative strategy for collecting samples from this species.

Collecting a muscle biopsy sample from a sandbar shark, a frequently encountered target species within the sanctuary. The shark is secured to the side of the boat during the tagging and sampling process. Photo © Carly Weldon

Collecting a blood sample from the caudal vein of a silky shark, another frequently encountered target species within the sanctuary. This smaller individual is brought onto the vessel during the tagging and sample collection process. Photo © Natalie Windels

So, what was my backup plan? Thankfully, I have been able to ask for help from some of my colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who were able to capture and tag a few scalloped hammerheads during their annual bottom-longline survey, but most individuals had to be let go before muscle and blood biopsies could be collected. Scalloped hammerheads are very susceptible to stress, so if an individual started to become lethargic during the capture-and-handling process the crew released it early. This allowed us to return the animal back to the water with the best chance of survival; however, that also meant that I was not able to collect the samples necessary for my trophic ecology analysis. What would be the point of developing a sampling method to reduce the mortality of an individual during the capture-and-handling process if they were released in a poor condition?

A researcher attempts to remove an aerator from a scalloped hammerhead captured on a NOAA longline survey prior to release back into the water. A satellite tag has been placed on the dorsal fin to track the spatial movements of this individual throughout the sanctuary. Photo © Kristin Hannan

A scalloped hammerhead returning to the water after a full workup. The hammerhead is resting in a shark cradle used to workup individuals captured during the annual NOAA bottom-longline survey. Photo © Kristin Hannan

Almost one year later, I am currently packing my bags and preparing for Plan C. During the month of September, I will join my colleagues at NOAA during the bottom-longline survey through the Gulf of Mexico to tag and collect the final biopsy samples I need from those elusive scalloped hammerheads. The NOAA research team is planning to use the capture-and-handling experiences from the previous year and are better equipped to efficiently tag and collect samples from any scalloped hammerhead that may be captured. I’m crossing my fingers because I’m feeling hopeful this time!