Exploring the conservation of sharks and rays at Watamu, Kenya

The conservation of natural resources, especially in poor regions where there is a strong dependence on these resources, is still an uphill task, with a multitude of factors in play. Numerous efforts have been made to address biodiversity loss, with varying levels of success. It has recently been brought to light that communities have a socio-economic, cultural and spiritual role to play in protecting species, and encouraging their participation in the process is now being recognised as a strong pillar of conservation. This emanates from the acknowledgement that whether a resource is exploited or protected is very closely linked to people’s spiritual and cultural perceptions of that resource – and that if these perceptions are carefully explored, they could provide a more meaningful reason for conserving nature.

Map showing Watamu Marine Protected Area in Kenya. Image © Google Maps

It is against this background that we have developed a project on a quite ‘unusual’ group of species and are integrating science with spiritual and cultural perceptions to promote their conservation. The group is elasmobranchs and it comprises sharks, skates and rays. Sharks are often feared as ‘monsters’ of the oceans, thanks to the misleading movies we have watched. In fact, elasmobranchs play important ecological and economic roles, but have been greatly exploited due to the increasing demand for their meat, fins and oil. Even worse, little research has been done on them; it is reported that the population status of nearly half of these species is poorly known.

School children drawing images of sharks. Photo © Peter Musembi

One of the main threats currently faced by sharks is the trade in their fins. Sharks are caught, their fins are hacked off and the animals are then abandoned to a slow and painful death at the bottom of the ocean. Although shark finning is not widely recorded in Kenya, evidence points to a growing trade in fins. For example, data indicate a high volume of trade in shark fins. Compared to the amount of shark meat traded in the same period, this suggests that shark finning could be taking place in the country. Overexploitation of other species for which there is high demand in Asia, such as sea cucumbers, is an indication of the direction in which the fin trade could be heading. The fins are used to make a ‘delicacy’, shark fin soup, especially in Asia. As a potential cultural or status symbol in that region, the soup has promoted the overexploitation of sharks all over the world. Another example is the spiritual practice of ‘shark calling’ in Papua New Guinea, which enhances shark conservation since only a few people ‘call’ sharks and bring in a single individual to be shared by everyone. In this case, a cultural practice promotes conservation. These are two examples of how important culture can be in helping or hindering conservation.

School children explaining the difference between sharks and rays. Photo © Peter Musembi

Our research has recorded as many as 10 elasmobranch species around Watamu Marine National Park and Reserve, some of which are listed as Endangered or Vulnerable on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. We have also observed some of these species in fishers’ catches. Our project aims to examine the diversity and the spiritual and cultural perceptions of sharks and rays in Watamu through research and education. In an area that supports a number of different religions and cultures, we want to understand how people perceive sharks and how their perceptions promote the overexploitation or protection of these species.

Setting up BRUV's for underwater surveys. Photo © Benjamin Cowburn

The project has been going for about a year now and already interesting patterns are emerging from both the communities and the ocean. For example, in our environmental education sessions we have observed that students are more aware of rays than of sharks and have seen more of them. In the field, we have also recorded more rays than sharks. Our talks with recreational divers have revealed that shark sightings are becoming increasingly rare. Also, it appears that most fishermen nowadays place no cultural value on sharks and rays, and the fact that few old or former fishermen seem to have much knowledge of them could indicate that cultural practices existed in the past but have been degraded over generations.

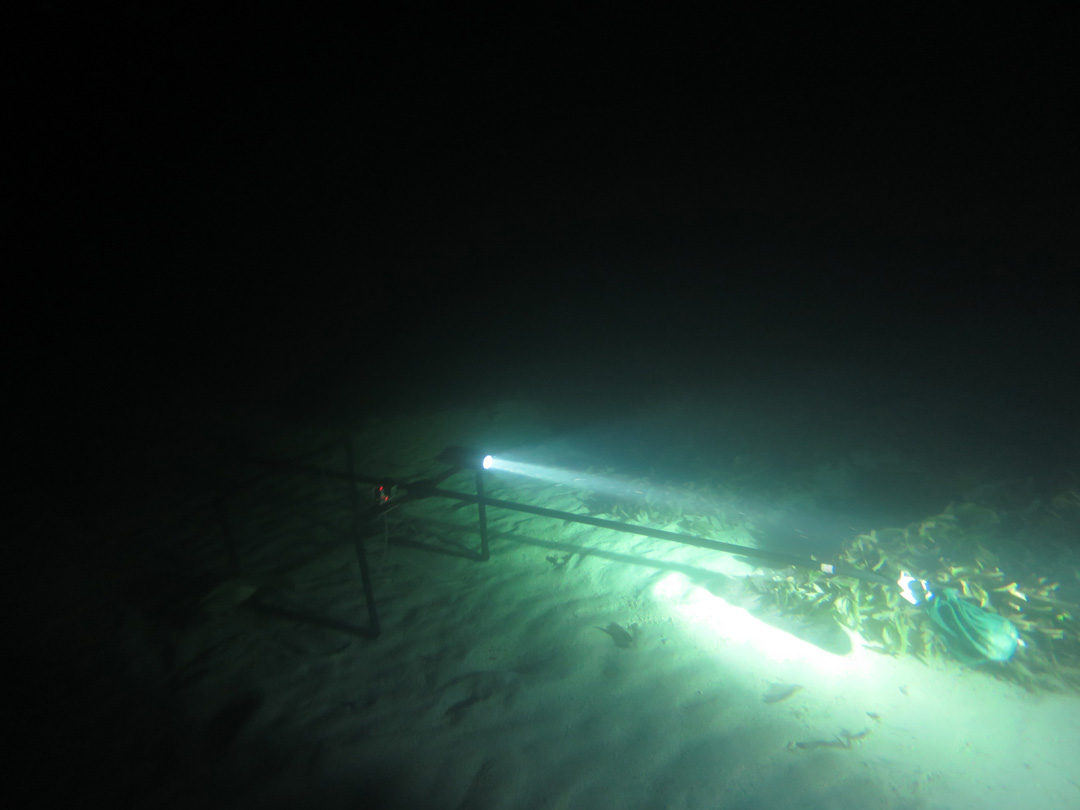

A set up BRUV for a night survey. Photo © Peter Musembi

This is a baby step in trying to tackle the conservation of sharks and rays in this part of Kenya, but I believe it is critical to understand what’s in play here. We hope to drive the conservation of elasmobranchs forward by integrating past cultural and spiritual practices into it.