Developing manta “Fitbits”: being part of cutting-edge research

Reef manta rays are charismatic animals, no doubt. Anyone who has ever swum with them would be inclined to agree. They are truly the gentle giants of the ocean, feeding on tiny plankton and often found getting cleaned at cleaning stations throughout their tropical and sub-tropical distribution. Their planktivorous diet, however, means they suffer a unique challenge: they must consume huge amounts of their tiny prey to meet the energy needs of their large bodies. This becomes even more challenging when we consider that plankton is a scarce and patchily distributed resource, and so manta rays must cope with ‘boom and bust’ feeding whereby they have periods of high food density followed by periods of starvation. As a result, manta rays must balance a tight relationship between energy gain, through feeding, and energy expenditure, through activity. An understanding of manta ray activity regimes and their relative energetic consequences is a pivotal next step in understanding manta ray functional ecology and their response to various threats. Despite this, it is difficult to study energy demands and activity regimes when we cannot directly observe them. Luckily, the development of animal-attached tags allows us to study many different facets of an animals’ ecology when we otherwise would not be able to.

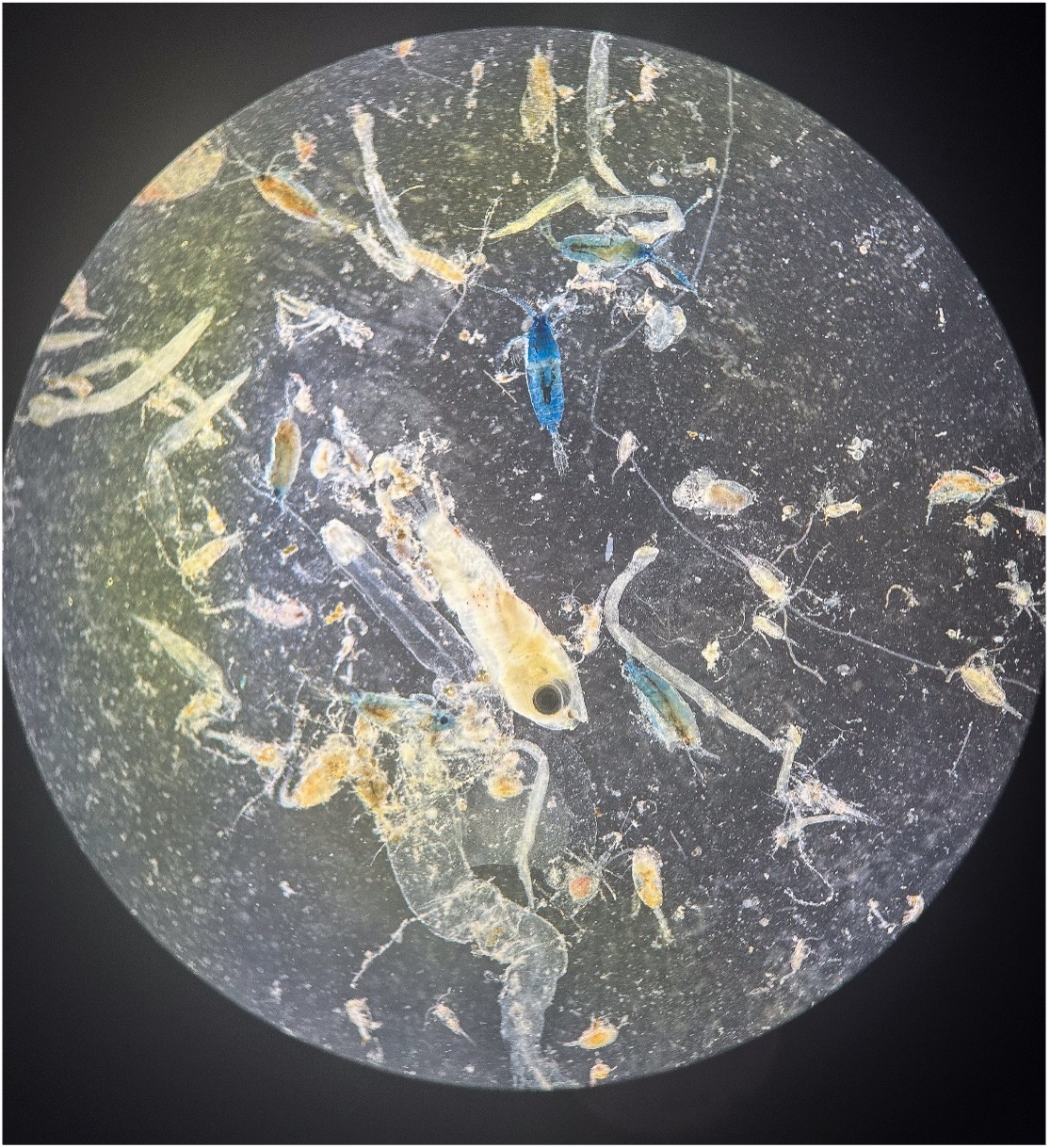

Plankton sample under the microscope. Photo by Dillys Pouponeau | © Save Our Seas Foundation

One particularly exciting avenue of animal-attached tags is the use of multi-sensor biologging devices. These devices are typically minimally invasive, collecting data for a pre-set period of time before self-releasing to be collected and re-used again. These cutting-edge technologies have a plethora of sensors onboard with electronics that are similar to what is available in our mobile phones. Depending what sensors are chosen for a specific tag, researchers can target questions regarding an animals’ movement, behaviour and even physiology (think: heart rate). To collect motion-sensitive data (e.g., tri-axial accelerometers) that can be used to study activity patterns in an animal, the tag needs to be secured to the animal and not wobble around. To date, we have been unable to put these tags on manta rays as their unique morphology (body shape) means the techniques used on sharks, turtles and cetaceans cannot be transferred across to these species.

My PhD as a Keystone Project Leader of the Save Our Seas Foundation studying at Murdoch University, Australia and with input from experts at the Manta Trust and Customised Animal Tracking Solutions (CATS) aims to overcome these challenges and develop a new attachment that will form the foundation for collecting such data on reef manta rays for the first time. The particular tag we have developed works like a manta rays’ personal “Fitbit”, allowing us to measure activity through ‘wingbeat frequency’; how often the individual moves its large wings up and down. Tagging manta rays with a tag that needs to be stationary comes with many challenges. The speed and manoeuvrability and cautious behaviour of manta rays makes approaching even the friendliest individuals quite challenging.

Fieldwork involves swimming as hard as you can against currents in an attempt to get close enough to deploy the tag, making it exhausting work. Already, so early on in my PhD and during my first fieldtrip here at the D’Arros Research Centre, I have learnt so much about how to develop and design a tag attachment that works for these gentle giants, and how to interact with them in a way that allows me to approach close enough to deploy devices.

Rachel following a manta with her tag while her buddy gets the ID shot from below. Photo by Henriette Grimmel | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Being at the forefront of such ground-breaking research is an incredible experience and such an honour. It is hard work, if it was easy it would have been done before, but it is incredible rewarding and exciting to be contributing to mobulid research in this way. Once a tag attachment has been developed and the baseline data collected for manta ray activity regimes and kinematics, the opportunities for what ecological questions we can ask about mobulid rays is expanded. I look forward to delving deeper into the activity regimes, relative energetics and kinematics of reef manta ray movement throughout this project.