Celebrating False Bay’s Marine Protected Areas: our marine playground!

Undeniable is the beauty of South Africa’s oceans, but beyond that marvel is their diversity. Our oceans are, in their own right, a host to their own rainbow nation.

Rocky shore of False Bay. Photo by Jamila Janna | © Shark Spotters.

For as long as we have been documenting our natural history in journals, marine resource conservation has sat high on the research priority list. Globally, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are one of the most promoted and supported conservation tools, with many in the developed world strongly rooting for 30% ocean protection by 2030. As described by the IUCN,

Two years ago on the 1st of August 2019, we witnessed 20 new MPAs taking effect a few months after being gazetted. This was after the 2011 National Biodiversity Assessment indicated that our offshore ecosystems were poorly protected. Prior to 2019, there were 25 formally declared MPAs which covered only 0.5% of South Africa’s oceans.

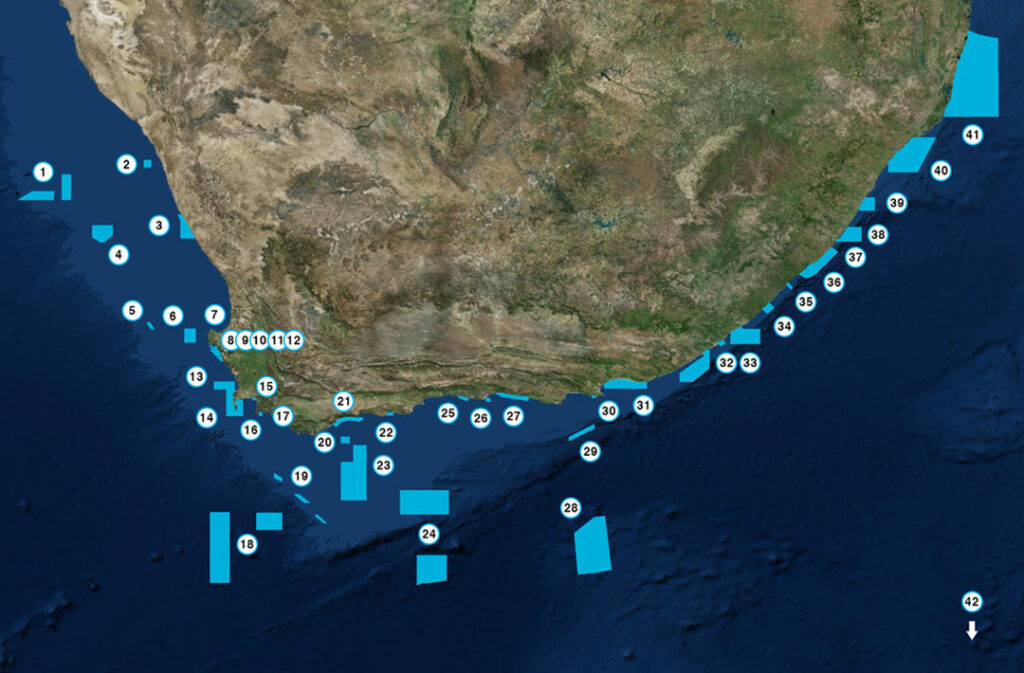

South Africa now has 42 Marine Protected Areas covering a total of 5% of our oceans, which includes the Prince Edward Islands, so has a long way to go to achieve the targeted 30% by 2030. On the 1st of August 2021, Mzansi celebrated the first-ever “MPA day” – a National Day of Significance that highlighted the value and diversity of these important conservation tools.

42 Marine Protected Areas of South Africa. Photo © SANBI.

Our MPAs act as sanctuaries for threatened and vulnerable species, giving them the time and space to recover from fishing pressure and other human-induced impacts. They are banks essentially, and the investment is our invaluable marine resources.

False Bay, where Shark Spotters operations are based, is home to two of South Africa’s MPAs; the Helderberg Marine Protected Area, on the north-eastern shores of the bay, and a portion of the Table Mountain National Park (TMNP) Marine Protected Area, on the western side of the bay.

False Bay is a marine biodiversity hotspot, designated as an EBSA (Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Area), due to the influence of both the Benguela and Agulhas ocean currents. It is also located on the doorstep of a major metropolitan centre and is therefore subject to numerous pressures and threats ranging from habitat degradation, pollution, fishing pressure and more. This makes the establishment and maintenance of these MPAs within False Bay critically important for the conservation of many endemic and threatened species, including sharks and other chondrichthyans.

So, what makes these two MPAs so important for False Bay’s diversity? And what is being done by local NGO’s such as Sharks Spotters for the bay’s sharks?

The Helderberg MPA is a no-take MPA and is situated on the northeastern side of False Bay. With a 4km sandy beach, a few low-lying sandstone reefs, kelp beds and pelagic environments make up the area. The beach itself has experienced little disturbance on the northern shores of False Bay and it is a sanctuary to the last relic population of the giant isopod Tylos granulatus.

However, true to human behaviour, part of the ecosystem has deteriorated due to the estuaries being subjected to water extraction, pollution and development outside the MPA. The good news and where hope lies is through the collaborative effort between City of Cape Town and the Shark Spotters in undertaking ecological monitoring programmes in the MPA.

Shark with a tag. Photo by Jamila Janna | © Shark Spotters.

On the other hand, the Table Mountain National Park (TMNP) MPA’s has two protection levels: 1) no-take areas and 2) controlled areas. The MPA lies in both transition zones between the Agulhas Ecoregion and the Cape region, which is an area teeming with marine species. The MPA is known to protect culturally significant areas which contain fish traps, numerous wrecks and traditional fishing.

TMNP MPA also holds great economic value due to the high levels of tourism, recreation, research and education taking place within the MPA. For example, the Shark Spotters Education Programme does rocky shore explorations with primary school learners, exposing our future generation to the marine environment early in their lives while promoting eco-consciousness. Furthermore, Boulders Beach is a favourite location for international tourists as it is host to the African penguin colony that settled there in 1982. African penguins are on the verge of extinction, so the protection afforded by the TMNP MPA is invaluable. The MPA is home to many such threatened and endangered species including white sharks (integral in Shark Spotters research), abalone, African penguins and several over-exploited line fish species, such as poenskop and red steenbras.

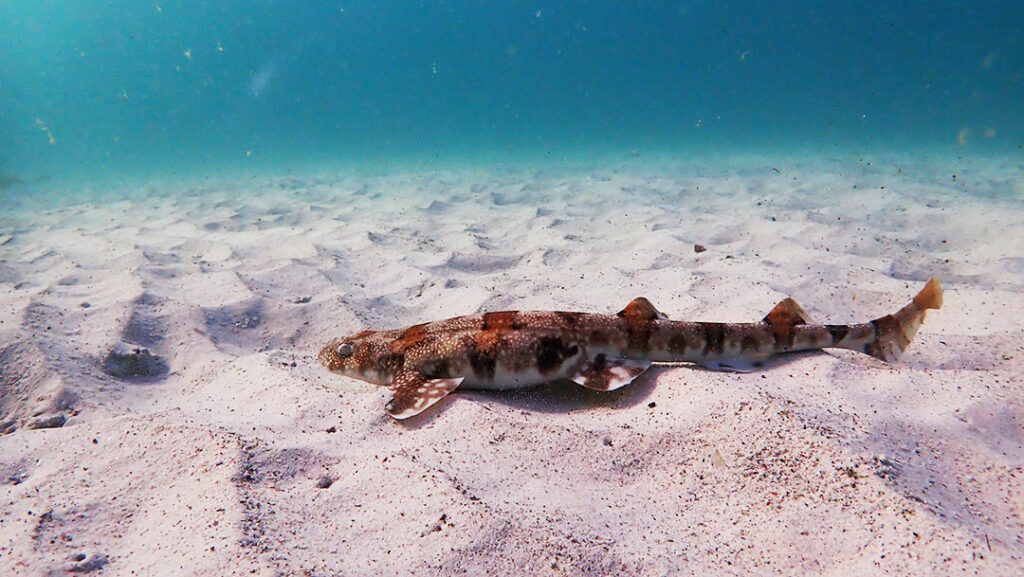

From a shark perspective, False Bay is an incredibly special place, and it’s MPAs provide valuable refuge for both sharks and their prey. The bay has historically hosted one of the largest seasonal aggregations of white sharks in the world, a spectacular phenomenon that is met with both awe and conflict from local water users. Aside from these iconic apex predators, a number of other shark aggregations are found in or near False Bay’s MPAs including spotted gulley sharks at Buffels Bay, Sevengill sharks at Millers Point, and in March 2021 the Shark Spotter’s team witnessed an incredible and unusual aggregation of bronze whaler sharks at Kogel Bay. The Bay’s kelp forests are teaming with smaller shark species including the endemic shy sharks and pyjama sharks, and it also plays host to a diverse range of rays.

Puffadder shy shark. Photo © Shamier Magmoet.

It is this abundance and diversity of sharks in False Bay that make its MPAs a playground for our Shark Spotters research team!

With projects focused on expanding knowledge on shark occurrence, behaviour and ecology, and managing shark-human interactions, the Shark Spotters research team and its collaborators have studied a number of shark species in False Bay including white sharks, broadnose sevengill sharks and bronze whaler sharks, using methods such as direct observations, satellite and acoustic telemetry.

False Bay’s MPAs have not just been a playground for Shark Spotters, whose research is crucial in maintaining shark biodiversity, but for the many endangered and threatened marine species who would otherwise be under threat outside the MPA.

With the management and expansion of our Marine Protected Areas, through government stakeholders, marine NGOs and passionate local heroes, the future looks good for our magical underwater kaleidoscope.