Cast a wide net…work; collaboration strengthens the accuracy and relevancy of conservation science

When undertaking a study that aims to obtain shark genetic samples across the extent of a species’ range, you’ll need a little help from your friends. That’s because collecting an adequate number of samples from enough geographic locations for a study to be representative is not only cost-prohibitive but time-prohibitive. There are simply not enough hours in the day, or days in the year for one research team to do so. To effectively and efficiently investigate the connectivity and potential persistence of an endangered shark species, it’s necessary to “zoom out” and gather information across their distribution to create accurate data that is truly relevant to the species’ conservation.

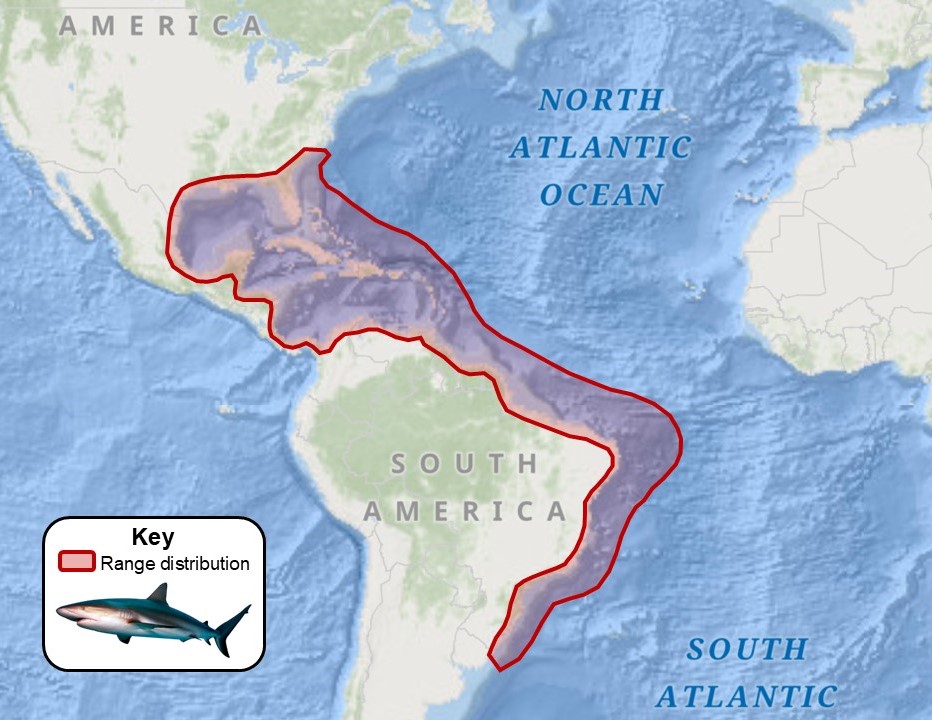

So, what does that geographic range look like for our focus species, the endangered Caribbean reef shark? This species occurs in the Western Atlantic Ocean, as far north as South Carolina, USA and as far south as Brazil/Uruguay (see Figure 1).

Range extent of the endangered Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi). Image © Steve Kessel | Shedd Aquarium Society

To date, we have obtained representative samples from a wide geographic distribution across this range. Caribbean reef sharks are more widely documented in the Caribbean region than in much of South America, which is also reflected in the distribution of our study samples (see Figure 2). In hand, we have ~425 samples, from multiple locations in eight countries, provided by collaborators from 15 different research groups representing universities, government institutions, and non-profits. The countries represented by these samples are The Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, The Cayman Islands, Colombia, Guadeloupe, Turks and Caicos, and the USA. We are confident that this distribution will provide an accurate representation of the genetic variability and connectivity for this species across different potential barriers to movement (e.g. very deep water or highly fragmented habitats).

Geographic locations of samples obtained that have been contributed to this study by collaborators to date. Image © Steve Kessel | Shedd Aquarium Society

Obtaining these samples took a lot of collaboration and coordination. We were able to activate our extensive shark research networks, which have been established over the years through past collaborative research projects and active mingling within the field at conferences. Our fantastic colleagues stepped up to help us make this study a success, first by agreeing to collaborate then by following through and sending their samples – samples that were collected through years of dedicated and gruelling field research. Typically, these collaborators are more than happy to provide samples as it gives greater productivity and worth to their past research efforts. For us, in addition to the obvious benefits for the study, it’s always a joy to walk into the office and find yet another package of samples sitting on our desks, not to mention the chance to catch up with long-time colleagues and friends. So, for any early-career scientists reading this, this is your call to action: proactively build a strong network of fellow professionals in your field.