Building a genetic roadmap for the conservation of the blackchin guitarfish

I still remember the first time I saw a blackchin guitarfish (Glaucostegus cemiculus). With their flat, spade-shaped heads and large, shark-like bodies, they are truly unique amongst sharks and ray alike. They have golden, sentinel eye, large dorsal fins, and tough skin. You get the real sense you are in the presence of a living dinosaur, of sorts, when lucky enough to encounter one. However, despite their charisma, these incredible animals are in trouble. They are among the most threatened marine fish on the planet, having completely vanished from many places they were once known to inhabit, likely a result of heavy targeted and non-targeted fishing, along with habitat destruction, combined with life history attributes that make them slow to recover (old age, late-to-mature, having few young).

Releasing the first ever blackchin guitarfish I saw during an initial exploratory mission to scientifically validate the presence of this species in Cabo Verde, West Africa. Photo © Dr. Manuel Dureuil | Sharks of the Atlantic Research and Conservation Centre (SHARCC)

To conserve a species, you first have to understand it. But when I started my Master’s research, we were missing a critical piece of the puzzle for the giant guitarfishes: a genetic “instruction manual” you could say. As such, during my master’s research at the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT), I set out to change that by assembling the first high-quality reference genome for this species, and for any member of the giant guitarfish family more generally.

Building a genetic map

Assembling a genome is a bit like putting together a massive billion-piece puzzle. Using a blood sample collected from a male blackchin guitarfish at the Nausicaá Centre National de la Mer in France, I used a cutting-edge “HiFi” sequencing technology that reads long, highly accurate strands of DNA to do so.

The result? A genome that is among most complete and contiguous shark and ray assemblies to-date. This is more than just a data point; it’s a permanent resource that researchers worldwide will be able to use to study the evolutionary history and genetic traits of these critically endangered fish.

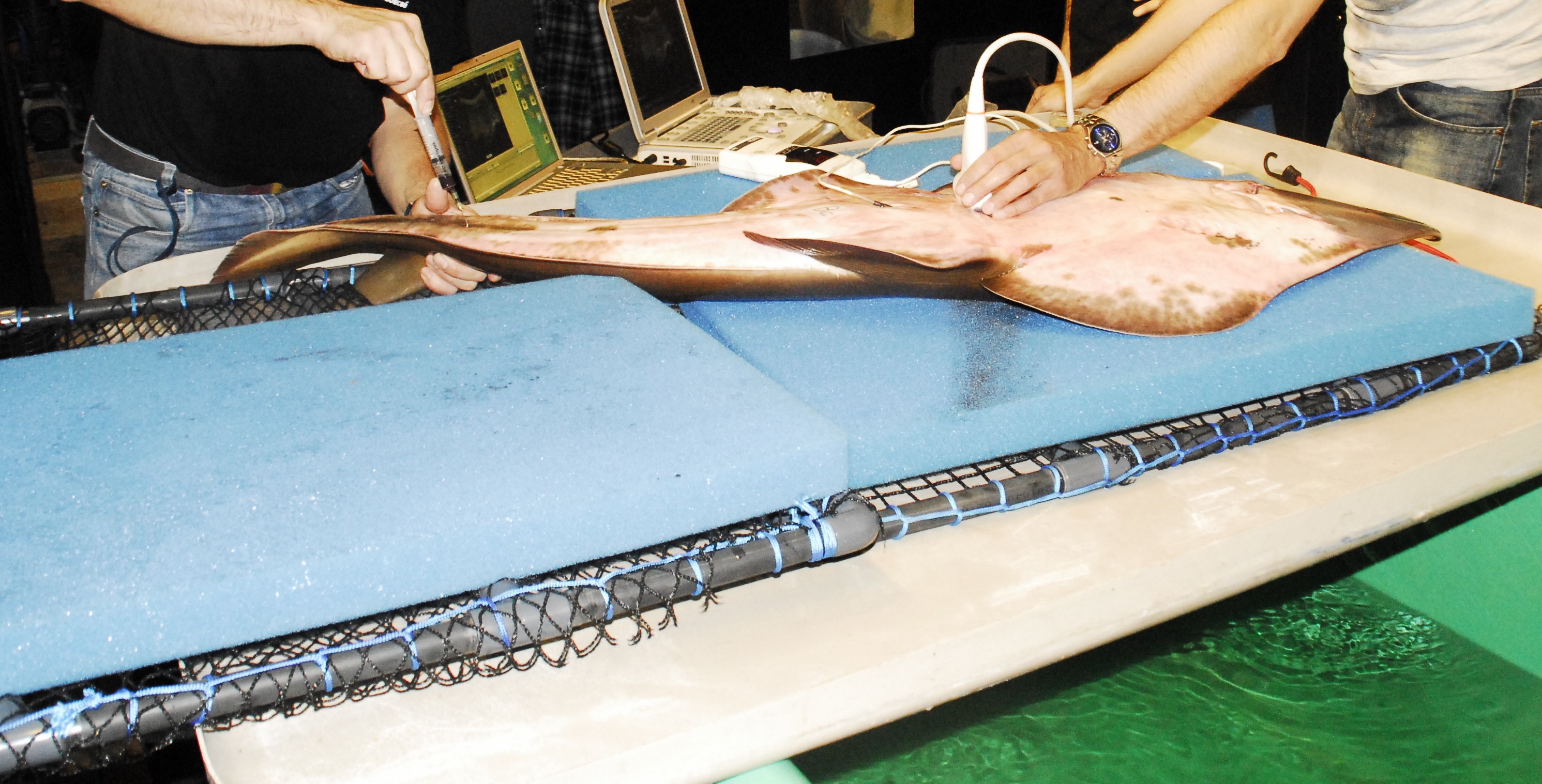

Research staff at the Nausicaá Centre National de la Mer in France perform a precise blood collection from a blackchin guitarfish. A sample such as this provided the high-quality DNA necessary to assemble the first reference genome for this species. Photo © Nausicaá Centre National de la Mer

From the lab to the wild: Cabo Verde

Now, the most exciting part of this work is seeing it in action. Currently, the Fish Ecology and Evolution Working Group at ZMT is using this new genetic map to analyse data from 47 individual guitarfish sampled on the islands of Sao Vicente and Santa Luzia, in Cabo Verde, as part of my involvement with the Cabo Verde Elasmobranch Research and Conservation Project, in collaboration with local NGO Biosfera. These two islands, separated from mainland Africa by a distance of ~750 kilometers with water depths often exceeding 1500m in between, seems to be a critical, yet geographically isolated area where these fish are still reliably found. It begs the question how genetically healthy the population there is, given their isolation between mainland populations, and the increasing fishing pressures they experience.

To do this, the lab at ZMT has identified nine special genetic “tags” (called microsatellite markers) from my assembled genome, that act like a biological “barcode”. By detecting variations in short, repeated sequences of DNA, these tags can reveal just how closely individuals are related through the patterns of alleles they share. Ultimately, this will help us map out the population structure and genetic diversity in Cabo Verde, giving a clearer picture on the genetic ‘health’ of this geographically isolated population. If the breeding population is too small, the species risks “inbreeding depression,” which can make them less resilient to climate change or overfishing.

By determining this population’s “genetic health”, we can give conservationists and policy-makers the information they need to aid management and conservation strategies for this critically endangered species.