Blue shark tags producing interesting results

This project was originally conceived to investigate the habitat utilization and fisheries vulnerability of thresher sharks in Australian waters. Following two years of fieldwork, consisting of 15 field trips and over 220 hours of active fishing for thresher sharks, we had only managed to deploy one satellite tag on a thresher shark in December 2012. The scope of our study has now been broadened to include blue sharks Prionace glauca due to their conservation status and difficulties in deploying satellite tags on thresher sharks.

The blue shark is one of the main by-catch species in open-ocean fisheries and accounts for around 50% of the total worldwide shark bycatch, and are considered to be the shark species with the highest total catch globally. This species has relatively high growth and fecundity compared to other chondrichthyans, and was previously thought to be relatively resilient to current fishing pressure. However, with the expansion of the Asian fin market in the 1980s, there was a large increase in the demand for blue shark fins. For example, in the Hawaiian longline fishery where no sharks were reported being harvested solely for fins prior to 1990, up to 61,000 individual blue sharks were caught and finned in 1998 alone. This increase in dedicated harvest caused population declines from the 1980s onward. Several papers have also documented evidence of declines (Aires-da-Silva et al., 2008; Baum et al., 2003; Simpfendorfer et al., 2002). Based on fishery-independent data from 1977 to 1994, Simpfendorfer et al. (2002) found evidence for an 80% decrease in the abundance of male, but not female, blue sharks, whereas an analysis of the US North Atlantic catch logbook data concluded an overall 60% decline in catches (Baum et al., 2003). The strength of evidence at present shows that some blue shark populations have declined and harvest rates require careful management and monitoring, particularly when there is the possibility of sexual segregation of populations and a likelihood of destabilising population structures (Mucientes et al., 2009).

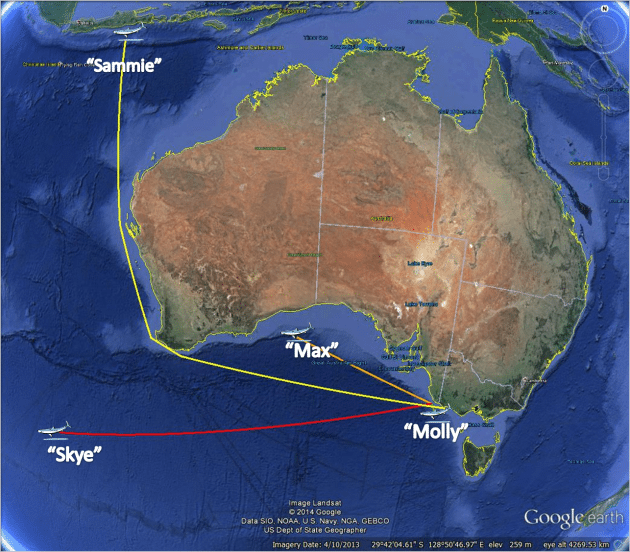

Deployment and pop-up locations for blue sharks tagged off southern Australia

Large Japanese longliner are operating off the Australian EEZ zone including off South Australia, that catches many blue sharks. We aim to tag blue sharks to estimate how much time they spend outside the Australian EEZ (providing an estimate of vulnerability/encounterability between blue sharks and that fishery). We will also tag males and females and determine the extend of movements of both sexes and assess if sexual segregation occurs. The information obtained will help improving the models used to assess blue shark sustainability and provide scientific evidence of their conservation status in Southern Australia which can then be used by managers/politicians to implement the necessary management regulations.

Five Microwave Telemetry Mini-PSATs were deployed on blue sharks ranging in size from 159 cm to 306 cm total length off Port MacDonnell in South Australia, and near Portland in Victoria. The tags were programmed to collect data for six months before detaching from the shark and transmitting the data using the ARGOS satellite network. The first four tags have all successfully released from the sharks with all deployments running their full course of six months with some very interesting data recorded, while the fifth tagged is still deployed and programmed to release in October 2014.

The Mini-PSATs do not provide real-time positions during deployments, but the minimum point to point distances that these sharks travelled are still staggering and very diverse between individual sharks. “Sammie”, a 215 cm female that we tagged near Portland, Victoria, travelled over 5,000 km up the west coast of Australia to the waters off Java, Indonesia. During the 180 days tag deployment, she travelled at the minimum speed of 30 km/day. At the other end of the scale, the tag that we deployed near Port MacDonnell on “Molly”, a 178 cm female, , popped up six months later only 62 km from where she was originally caught.

While the pop-up locations were very interesting, the depth and temperature data transmitted from these tags has already revealed some intriguing behavioural differences between the tagged sharks. The dive profile of “Max”, the 302 cm male, is quite different to the dive profiles of the smaller female blue sharks. While “Max” made some deep dives, one as deep as 560 meters, he remained shallower than 50 meters for the vast majority of the deployment. In contrast, the three small females made frequent and repeated dives deeper than 300 meters throughout the whole duration of the deployment. This suggests that the vertical distribution of large sharks might be different to that of small sharks, which could be driven by differences of feeding strategies and preys. The differences in depth utilisation are clearly shown in the percentage of time at depth graphs for these four sharks.

We eagerly await the pop-up date of the last tag that we deployed on another small female blue shark (158 cm), which we expect to release and transmit in early October 2014. In addition to this we aim to deploy a further four satellite tags on blue sharks in the next couple of months.

The next step for this project is to use the depth and temperature data collected by our tags to investigate in more detail the vertical habitat of blue and thresher sharks in Australian waters. We will also combine this data with light data recorded by our tags to provide better estimates on each sharks locations throughout the duration of these deployments. The results of this analysis will be used to compare the habitats of blue and thresher sharks with other pelagic shark species.

References

Aires-da-Silva, A. M., J. J. Hoey, et al. (2008). “A historical index of abundance for the blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the western North Atlantic.” Fisheries Research 92(1): 41-52.

Baum, J. K., R. A. Myers, et al. (2003). “Collapse and conservation of shark populations in the Northwest Atlantic.” Science 299(5605): 389-392.

Mucientes, G. R., N. Queiroz, et al. (2009). “Sexual segregation of pelagic sharks and the potential threat from fisheries.” Biology Letters 5(2): 156-159.

Simpfendorfer, C. A., R. E. Hueter, et al. (2002). “Results of a fishery-independent survey for pelagic sharks in the western North Atlantic, 1977-1994.” Fisheries Research 55(1-3): 175-192.