Acoustic telemetry diaries: two years in the life of Scout the pygmy devil ray

One of the key objectives of our research project is to understand where, when and why pygmy devil rays move in the Gulf of Mexico. Do they migrate across long distances? How fast? Is there a seasonal pattern? What are the main drivers of their movements? Correctly answering these questions using acoustic telemetry requires a large enough sample size (number of individuals tagged and number of detections) that can only be reached through years of tagging and monitoring efforts. Although we are still putting the pieces together, some of the first devil rays we tagged have now been detected for two years, providing the very first insights into the species’ movement ecology. Mh104, or “Scout”, is one of them, and as his name suggests, his journey so far has exceeded all our expectations!

Scout is a subadult male of 88.2 cm disc width (~3 feet across) that we encountered in Sarasota on October 12th 2021. At that time, Florida’s Gulf Coast was facing a harmful algal bloom (a.k.a. “red tide”) event with higher-than-normal concentration of the microscopic algae, Karenia brevis. This algae defends itself from predators by producing toxins that can affect the central nervous system of marine animals. An additional side effect is low oxygen concentrations in the water which can cause large fish kills. So imagine our surprise that day when after hours on the water searching for but not seeing any wildlife with the exception of dead floating fish, we found this devil ray swimming along the shore! We kept him under observation for a few days in a separate tank at Mote Marine Laboratory, before acoustically tagging and releasing him into the Gulf. This is how Scout’s journey under our watch began…

Project leader Atlantine Boggio-Pasqua and Scout the pygmy devil ray upon release in the Gulf of Mexico off Sarasota, Florida. Photo © Kim Bassos-Hull | Mote Marine Laboratory

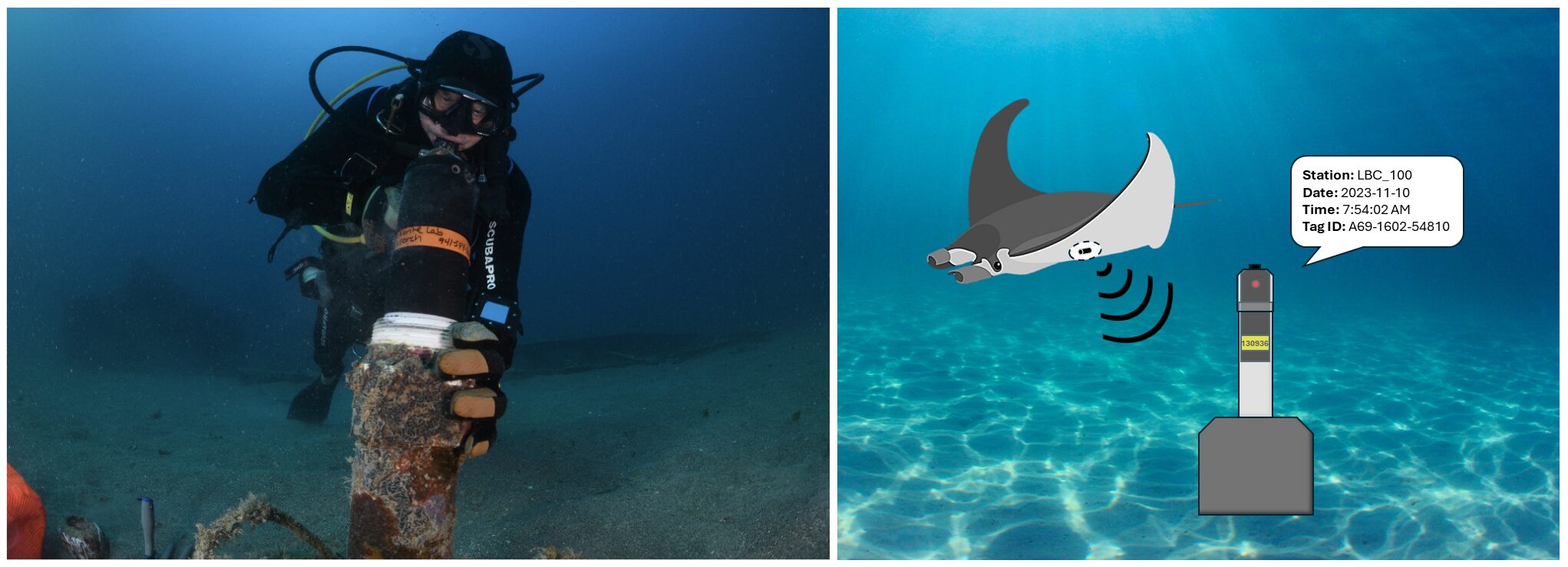

How did we keep track of Scout’s whereabouts? Acoustic telemetry is a handy tool used by many researchers across the globe to study animals’ movements. The principle is simple: an individual is internally or externally equipped with a transmitter/acoustic tag that emits a unique ping at regular time intervals until its battery dies. The more frequent the ping, the shorter the battery life. Researchers design arrays of receivers in strategic areas in order to monitor their target species’ movements. When a tagged individual comes near a receiver, the unique ping is detected and recorded along with a timestamp. Individual movements can then be inferred from successive detections at multiple receivers. However, there is no real-time transmission of the data, receivers have to be physically recovered and downloaded at the surface, which is typically done once a year and combined with a battery swap. In the northern Gulf of Mexico, there are currently over a thousand receivers deployed along the coast, which is an ideal set-up to identify migratory behaviours.

Using acoustic telemetry to study marine animals’ movements: (left) Mote Marine Operations Greg Byrd deploys a receiver within the SCAN (Sarasota Coastal Acoustic Network); (right) each tag/transmitter produces a unique ping that can be detected when the animal swims by a receiver. Photo © Andy Deitsch

Since October 2021, Scout has been detected 1602 times on 86 different receivers. He traveled a minimum of 3350 km in 2 years! He is the first of our tagged devil rays to have completed two return migrations between his tagging location, Sarasota, and the Florida Panhandle. His quickest move northward was in December 2022: he swam 486 km in just 12 days. Below is a 30-second animation illustrating his successive known locations.

Scout’s (Mh104) known locations between October 2021 and October 2023 based on acoustic detections at receivers in the Gulf of Mexico. The still red dots are locations of detections while the moving red dot reflects a fictive linear movement at constant speed between successive detection locations.

Going north in the late fall/winter and going south in the spring/summer – we are observing this seasonal migratory behaviour in other subadult devil rays, both males and females, but do juveniles and adults follow the same pattern? What drives them to either region: temperature? Probably not, since they are moving north in the coldest months, and south in the warmest months… food? Probably! We discovered that they feed on dense patches of mysid shrimp along the Panhandle beaches in the fall and winter (see our previous blog article). Their regular food sources in the Tampa Bay-Sarasota area have not been clearly identified yet but we are starting monthly sampling tows to look at zooplankton seasonal abundance and diversity.

One downside of acoustic telemetry with migratory species is that there are considerable gaps or “blind spots”: we only know about the animals’ locations when they are near receivers. Some parts of the coast have more receivers than others, or no receivers at all, so we have likely not yet captured the full extent of pygmy devil rays’ migrations in the Gulf of Mexico. Additionally, receivers are mostly deployed in coastal, shallow waters for ease of deployment, fixation on the seafloor and servicing, which leaves most of the Gulf unmonitored. This is why we are starting to deploy satellite tags as a complementary approach to determine if and how pygmy devil rays use deeper waters.

Last but not least: acoustic telemetry studies take a village! Collaboration is a key component of this technique, with researchers sharing the orphan detections on their receivers to the tag owners through matching platforms such as iTAG (Gulf of Mexico) and FACT (Atlantic Ocean). Many thanks to Robert Ellis (FWC), Susan LowerreOn a mission for missing information about ‘mini mantas’ in the Gulf of Mexico-Barbieri (FWC) and Dewayne Fox (Delaware State University) for sending us their detections of Scout over the past two years!

Life of pygmy devil rays in the Gulf of Mexico is still full of mysteries, but it’s incredibly exciting to see the first pieces of the puzzle come together to help better understand and preserve this endangered species. Stay tuned for more project updates in the coming months!