A thank you to the south Florida shark diving community.

After two years of gathering preliminary data on silky sharks in south Florida, we’re starting to recognize some individuals.

This means that at least some of the silky sharks visiting east Florida in summer exhibit philopatry (i.e., they return to this area, possibly annually). We don’t yet know why they do this, but two things often motivate sharks to return to the same place: reproduction (including mating and giving birth) and feeding. Hopefully, future research can help us understand why these silky sharks are here, and our tagging data will tell us where they go between South Florida vacations.

A pop-up archival satellite tag attached via bridle attachment at the time of deployment. Two other common tag types are visible as well. A dorsal tag for visual ID (yellow top) and a dart tag for ID upon recapture (yellow bottom). Photo © Brendan Talwar

I use the word ‘vacations’ intentionally – these sharks are big adults that probably spend most of their time off the shelf in very deep water and travel through international waters and multiple jurisdictions (e.g., Bahamas, USA, Cuba). Off of Florida’s east coast, silky sharks are relatively protected from exploitation – pelagic (i.e., open-ocean) longline gear is banned in parts of the region and silky shark retention is largely prohibited in U.S. federal waters and state waters. But, in much of the western Atlantic Ocean, silky sharks are exposed to commercial longline fishing and suffer mortality from accidental and targeted capture. These interactions pose a risk to silky shark populations and motivate fisheries management organizations to minimize their impacts on silky sharks (and other bycatch species). To achieve that goal, they need to know where silky sharks spend their time, both across ocean basins and up and down in the water column. We’re collecting that information with satellite tags.

One of the sharks that recently returned to South Florida was easily identified – its pop-up archival satellite tag, or PSAT, never popped-up. Our team received photos of it swimming off Jupiter in early July 2022, almost one year after we tagged it in the same area (see last year’s blog post). Unfortunately, the tag didn’t detach when it should have after a four-month deployment, and was instead still attached after one year, making its deployment 3 times longer than intended. Although this does happen on occasion, the opposite happens more often: tags regularly detach early due to malfunctions or deployment errors, which makes us scratch our heads for days, playing the blame game. Did we crimp it poorly? Did we program the tag incorrectly? Maybe another shark bit the bridle and the tag floated to the surface? Maybe the shark cut it off on a sharp piece of an oil rig? The possibilities are endless and make this aspect of our work frustrating. Given the cost of a satellite tag ($4,000 each), plus the cost and effort associated with deploying a tag on the right shark in the right geographic location, we cannot overstate the importance of tags staying attached for the full intended duration.

Most likely locations of the silky shark from the time of tagging off Jupiter until the tag's battery died months later. Figure © Brendan Talwar

Primarily, for this reason, we prefer to tag sharks with a bridle attached to the first dorsal fin. Bridles are made of monofilament or wire that we wrap in anti-chafe tubing or surgical tubing. This gets threaded through a small hole that we make in the leading edge of the dorsal fin. The dorsal fin is made of cartilaginous rays, so creating this hole is akin to a person getting their ear pierced – there is no bleeding at the attachment site and the shark rarely flinches. The tag is then crimped to the loop threaded through this hole and sits behind the dorsal fin of the tagged shark until its predetermined pop-off date. The tag’s positive buoyancy keeps it off the shark’s back, and the tag’s position makes it difficult for the shark to pull it off. It is a sturdy and dependable attachment method. When the tag’s deployment is over, a corrodible pin inside the tag’s nose is supposed to burn off, and the tag should float to the surface. The only remaining evidence of the PSAT will be the loop of wire or monofilament running through the dorsal fin that can be easily cut off or will shed on its own when the crimps rust away. Sharks can also pass all manner of objects through their tissue, some of which are far more impressive than this. For example, one lemon shark was observed over the course of 2 years while it slowly forced a metal object from inside its stomach through the side of its body cavity entirely.

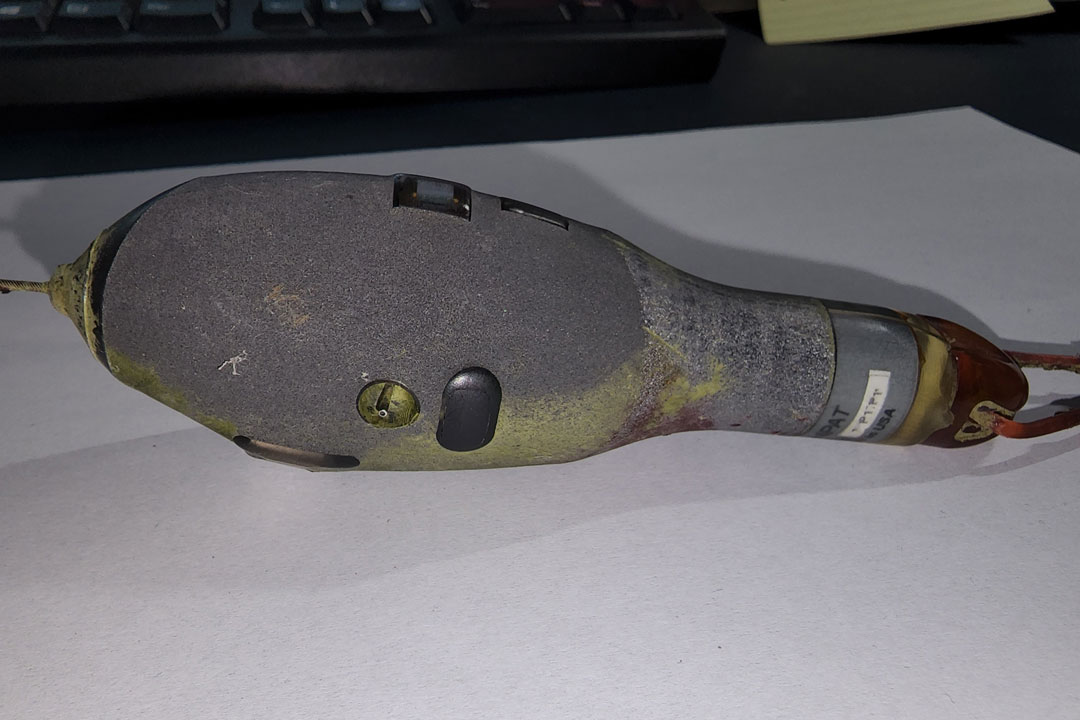

The recovered pop up archival satellite tag after being removed from the silky shark. Photo © Brendan Talwar

We are very thankful to Florida’s shark diving community for sharing photos of this shark with our research team before cutting the tag off despite ample opportunity to do so. We greatly appreciate your restraint and open communication and take your observations to heart. We will use your observations to inform our tagging protocols, including decisions about tag type, attachment method, and necessary sample sizes. We have tagged other animals this year in similar fashion, and removing those tags early would be very detrimental to our research. But this particular tag was never going to release on its own, and we would have probably never heard from it again. Thankfully, Diana, a local dive professional, cut the tag’s bridle, and we were able to send it to the tag manufacturer. When a tag releases the way it should, it often transmits less than 80% of the data it collected via satellites, but we received 100% of this tag’s data via direct download at very high resolution (a depth and temperature record every 3 seconds!). Importantly, this shark is also free of research equipment and will heal fully.

Even if you don’t know whose tag you’re seeing, please send us a photo! We can figure out who it belongs to and whether it failed to detach; the research community is quite small. And if you’re able to safely lend a hand after getting in touch, we’ll be incredibly thankful.