A Return to the Sea

As South Africans, we’ve inherited a phenomenal wilderness heritage. However, the majority of citizens in our beautiful country will never experience this, or grow to understand its value and love its unique diversity. Barred from our remaining wild spaces by prohibitive entrance fees, long distances across a variable country and gaps in communication, it’s unlikely that the average South African will ever know the thrill that an encounter with a lion brings (aside from when it is raiding livestock or considered an unwanted intruder outside its reserve fencing) or feel that deep sense of reverence for a sunset over an untamed land.

If a visit to the Kruger National Park or the Kgalagadi is a far-off dream or luxury, even more unlikely is the idea that most South Africans will ever dip their bodies below that blue expanse to experience our last great wilderness, the ocean. By this I don’t mean a quick frolic in the waves on public holidays, when South Africans crowd the beaches along our coastline in search of revelry and the joyous feeling of salt spray on their faces. I mean rather that for those who cannot hold their breath long enough to meet the ocean’s otherworldly creatures and who will never inhale from a SCUBA tank to prolong an encounter with a nudibranch, our oceans remain an intangible realm and their inhabitants, incorporeal creatures of an alien world.

So how can we, as marine conservationists, ever hope to achieve support for impalpable concepts like “marine protected areas”, closed seasons, bag limits and permits?

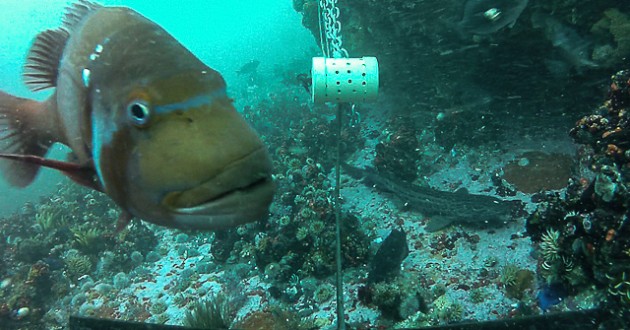

My thinking has, of late, been directed around how it is that we achieve conservation messaging. You see, the False Bay BRUV project has opened up, aside from its scientific pertinence and management implications, a role for scientific videos in education and marine awareness that I’d previously had trouble convincing people would necessarily work! The charm of False Bay’s fishy locals has endeared a wider audience than I thought possible to the bay and its diverse marine inhabitants.

Musing on the idea of where exactly BRUVs slot into the realm of awareness, I’ve considered certain ideas. Firstly, BRUVs, rather than showing what is missing from or wrong with an ecosystem, tend to make tangible what is left in an area. Of course, we use the data from BRUVs to extrapolate what species we have not picked up (whether that be the result of the technique itself, or the conservation status of the species in question) but from a public awareness point of view, the videos communicate interesting species and behaviours in the wild that people might not otherwise see for themselves.

Sometimes, in an age where the dissemination of news via media channels is astoundingly rapid and the quantity of news we receive on a daily basis mind-boggling, differentiating your message is key to reaching an otherwise desensitized audience. Of course, the horrifying truths of environmental challenges need to be communicated – shark finning, for instance, is a complex problem that should not be trivialised in its communication to a public audience.

My point however is that, in marine conservation, our first step is to establish a connection. Support for something that is intangible is an almost impossible goal to achieve (note, I said almost). A few weeks ago, I gave a talk on sharks to group of children who had never seen a fish underwater before and who thought that the university we were lecturing at was a hospital. If I had started this particular talk about shark conservation with shark-finning and other complex issues, my entire hour would have been a waste. Instead, I had to introduce these children to the sea in its entirety, as something that was an entirely new concept to many of them. In a way, this is the most wonderful way to go about awareness, remembering the sense of wonderment that first endeared me to the ocean, and communicating that to a new generation.

Sometimes, to do this, it’s nice to be able to come from a place of inspiration, rather than desperation.

The following is a little video that a friend of mine, Otto Whitehead, and I put together on this very topic. I’m happy to say that since it was made, the oceans’ protective cover has increased to just over 2% after the promulgation of the Cook Islands’ reserves.

Put on a good set of headphones and enjoy.