A change of scenery

The months of June and July saw a complete change in my working routine. Instead of going to work in a small kayak equipped with shark work-up equipment and huge water bottles to keep us hydrated, I drove a small red Toyota through the busy traffic of South Florida. Early every morning I would leave my Fort Lauderdale home and drive south on US 1 to the beautiful John U. Lloyd Beach State Park at Dania Beach. At the end of this park, right next to where many cargo and cruise ships offload at the huge Port Everglades terminal, I would come to the Oceanographic Center. This is home to the Save Our Seas Shark Research Center (SOSSRC) laboratory, a modern and renowned shark genetics lab led by Professor Mahmood Shivji. I’d heard a lot about this place, read its publications and even personally met Professor Shivji when I was a Master’s student at the Bimini Biological Field Station in 2011. Therefore the opportunity to analyse my first batch of the stomach contents of juvenile sharks at this lab was a great honour for me.

Different ways of commuting to work: my kayak at the St Joseph Atoll versus my car in South Florida. © Photo by Ornella Weideli | Save Our Seas Foundation

Inside the building, the working conditions couldn’t be more different from what I’m used to at St Joseph Atoll. I left my shark work-up kit on the island and swapped sunglasses, buffs and a hat for a laptop, proper clothes and shoes. Instead of being surrounded and assisted by my field team 24/7, I had to adjust to working regular hours and mainly by myself. My days at the lab were dominated by pipettes, gloves, tubes, centrifuges and protocols, which I used to analyse the stomach samples step by step. At first two microlitres seemed to be unbelievably small, but I quickly adjusted to the tiny volumes and the minuscule 0.5-millilitre tubes. After the first few days had passed and I had asked the lab’s Master’s students Cassie and Cristín all kinds of questions, I gained more confidence, improved my knowledge of the protocols and soon started to get my first results.

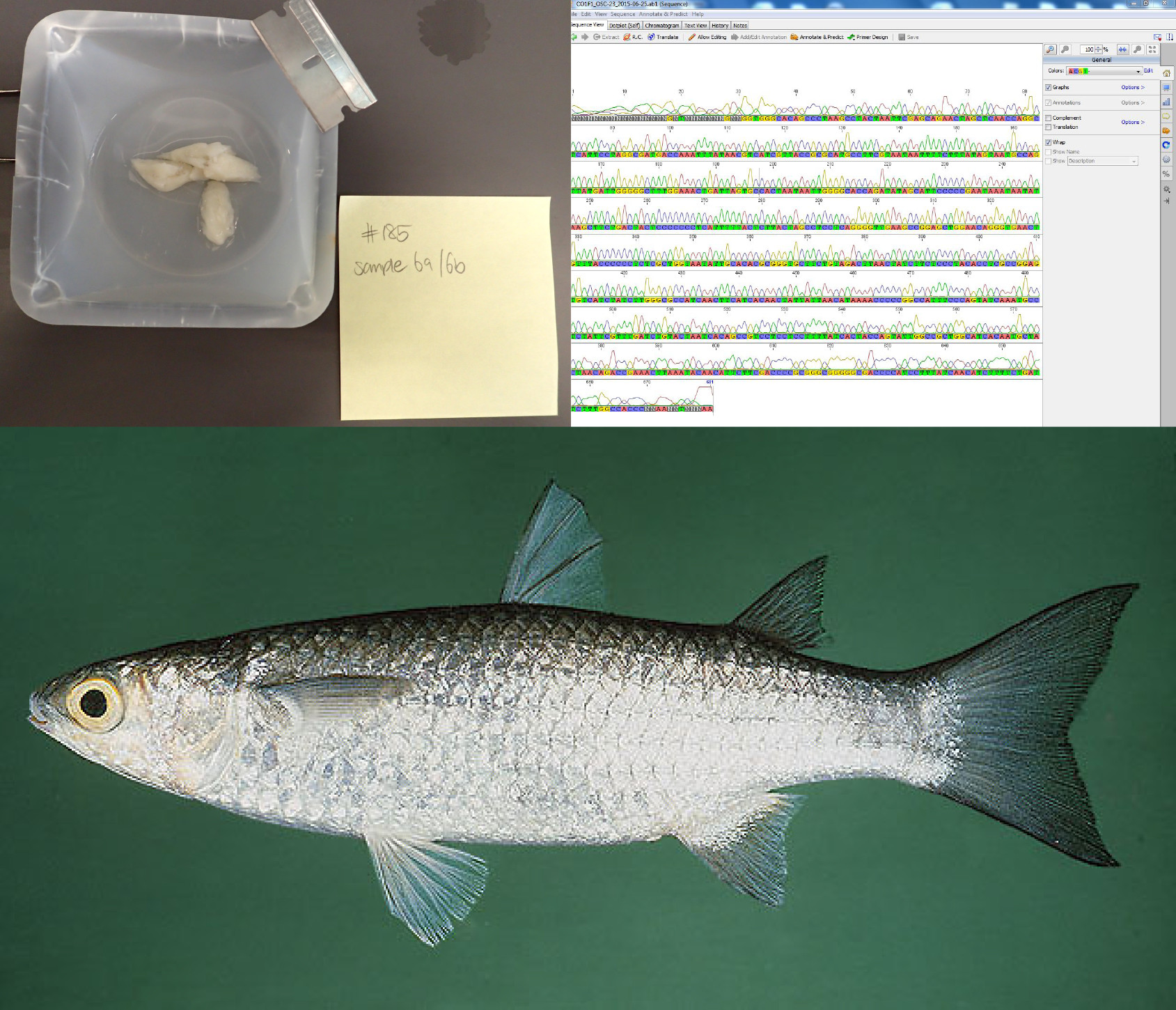

In a genetics lab, final results can be composed of a sequence of only four letters: ATGC. What may seem like an unsatisfying result after long and exhausting days of lab work is actually quite the opposite! The sequence and length of these four letters constitute the genetic code of all living species and serve as a unique genetic fingerprint. By ‘reading’ a specific part of this sequence and comparing it with a database, I could identify the species of the consumed prey. St Joseph Atoll is home to a dense population of mullets that we see regularly when working in the atoll. Therefore I was not surprised to find, besides other atoll teleosts and crustaceans, largescale mullet Chelon macrolepis in the stomachs of the juvenile sharks.

Wonders of today’s lab methods: from small, unidentifiable and half-digested chunks of stomach contents, I was able to extract DNA that told me the origin of the sharks’ food – in this case, a largescale mullet. © Photo by Ornella Weideli | Save Our Seas Foundation

In summary, my few weeks at the SOSSRC were a total success. Not only was I able to determine what juvenile lemon and blacktip reef sharks are eating, but I also realised once more what a privilege it is to execute a project from A to Z. I’m still fascinated that we found and caught these juvenile sharks, sampled their stomach contents non-invasively, prepared and shipped the samples to the USA, and then identified the origin of the sharks’ meals. My curiosity about biology never ends, and this trip to Florida was a perfect combination of learning new methods, working in a new team and adjusting to a different lifestyle.

Once again, thank you Mahmood for giving me the opportunity to analyse my samples at your lab. I had a wonderful time and learned various new skills. Thank you also Cassie, Cristín and Andrea for your incredible help and support during my stay at the lab; Igbal for your friendship and your motivating words; and my dear Florida families (Doc and Marie Gruber, Jeff Trotta and Missy Belsito) for your hospitality and immense kindness.