50 ways to start your PhD

Blame it on my musical family, but there’s been a catchy percussive beat knocking around inside my head for several months now. As each day brings some new challenges, the marching band-style drums kick into a more upbeat riff and the lyrics launch into a string of advisory phrases:

‘Just slip out the back, Jack.’

‘Make a new plan, Stan.’

‘You don’t need to be coy, Roy – just get yourself free!’

As engineers delayed construction, equipment broke (and was fixed, and broke again) and it seemed that the number of surveys we needed to get our vessel through changed daily, Paul Simon’s advice became increasingly tempting to follow. Launching a PhD, it would seem, is time-consuming, challenging and a probable explanation for any rise in yoga subscriptions at the university’s gym…

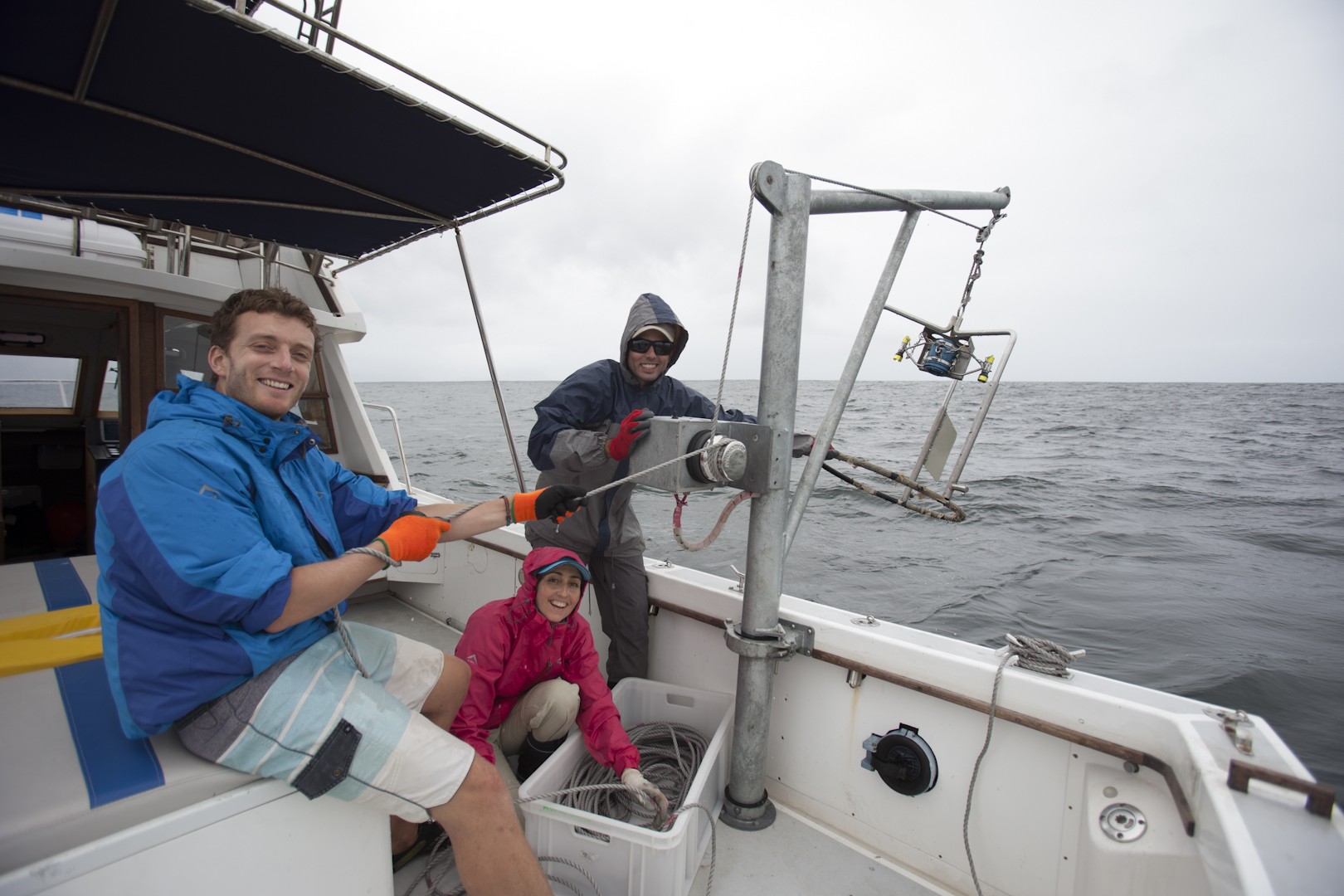

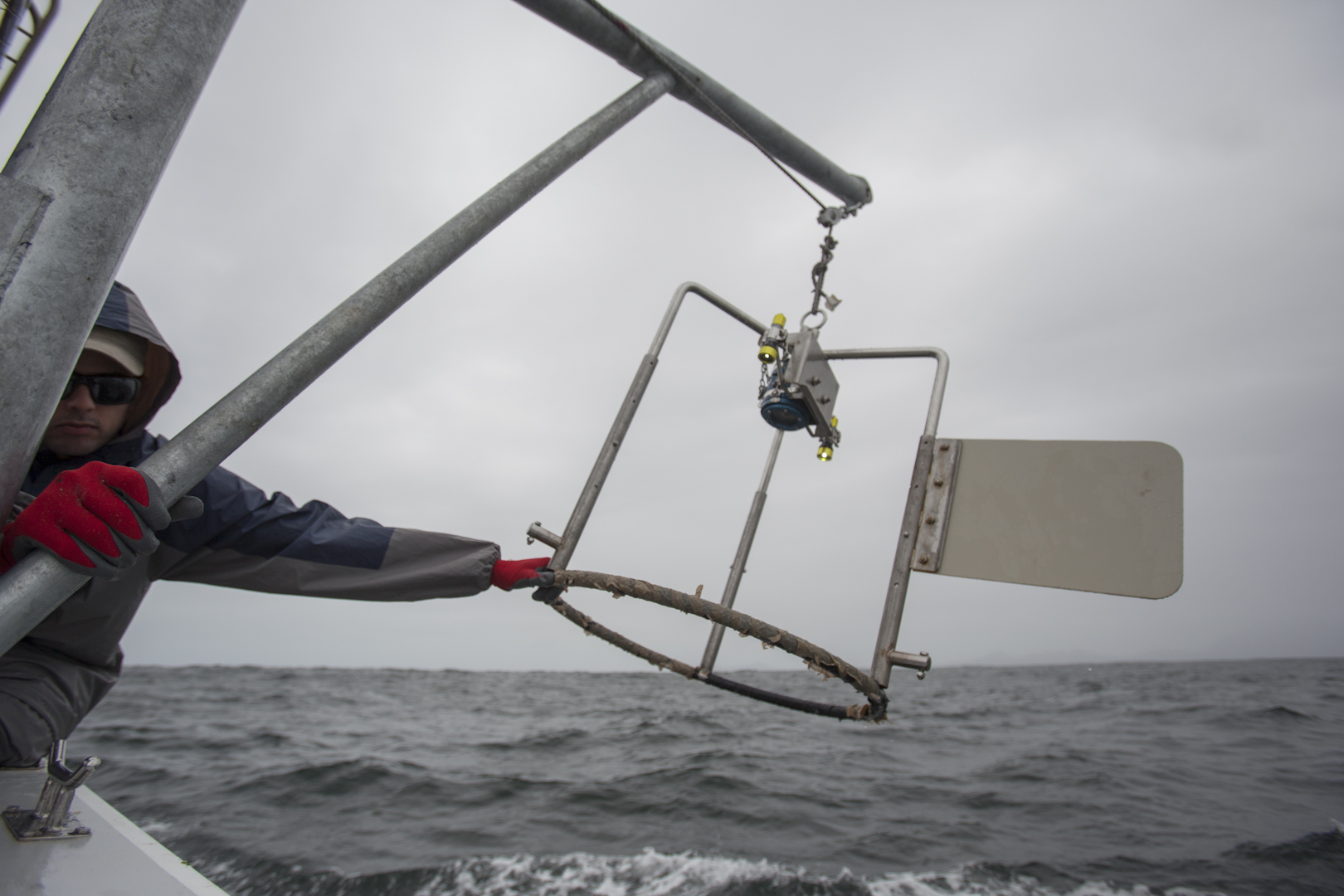

Lauren’s brother Marc and Rhodes University PhD student Denham Parker operate the capstan winch to haul the jump-camera rig to the surface. For one or two sites in shallow water, the 30-kg rig can be hand-pulled. But in a survey to a depth of 80 m, the winch becomes a valued necessity! Photo: Mike Kendrick.

With apologies to Simon’s songwriting, I’ve already betrayed the end of this blog in its title –because it’s not ‘50 ways to leave your PhD’! Instead, I have been spending many hours at the False Bay Yacht Club preparing our research vessel Sargasso for the very first biodiversity survey of False Bay that uses only remote-camera technology to map the distribution and abundance of invertebrate and fish life in the bay. This, it turns out, is no small task and requires getting to grips with far more engineering know-how than a biologist ever anticipated (but my knot-tying has improved magnificently!)

Finally Sargasso was seaworthy and my colleagues at SAIAB (South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity) and the Elwandle Node of SAEON (South African Environmental Observation Network) had delivered our equipment to the Shark Education Centre. Now all we had to do was watch False Bay’s mercurial moods vacillate wildly before choosing the right conditions in which to go into the field. As any local will tell you, the nickname ‘Cabo Tormentoso’ (Cape of Storms) bestowed on this region by the Portuguese mariners of yesteryear is apt. Strong summer winds and the resulting poor visibility that divers expect of False Bay at this time of year have been matched by large, unseasonal swells more typical of winter. As we spent many frustrating shore-bound days watching the white horses race across the bay, a jaunty little refrain snuck back into my mind: ‘Just hop on the bus, Gus – you don’t need to discuss much!’

Luckily, my musical background ensured that my repertoire of song references was broad enough to find some other inspiration. Not even one month after we first launched, I have collected nearly 300 photographs of the sea floor that I will analyse to understand the distribution of key invertebrate groups. They have been taken by our jump camera, a locally built construction with a downward-facing GoPro camera in a customised housing that can go down to 250 m. I set the camera to take still photos at five-second intervals and we lower the rig to the sea floor using our capstan winch setup. After it’s been on the bottom for 30 seconds, we haul it to the surface and move a few hundred metres to the next site. We work like this along the length of a transect that I’ve designed to go against the depth gradient in the bay (we work from shallow to deep sites on a daily basis).

A photo from the jump camera at 52 m. Rock lobsters Jasus lalandii are listed as orange on WWF’s SASSI (sustainable seafood) index and are a source of much current contention in South African fisheries management. Getting a handle on the relative numbers and distribution of invertebrate species like these is what my jump-camera survey is all about. Photo: Lauren De Vos (UCT and SAEON).

I am hoping that the information we collect in this way can add to the original invertebrate surveys done using soil dredges and grabs, and by scuba divers in the 1960s. Not only will it update the records, but it will offer a non-extractive means of identifying large invertebrates that inhabit the sea floor. The data I analyse will form the first research chapter of my PhD and will give us a better understanding of patterns in invertebrate diversity across the region.

And the broader purpose of these data? Sound conservation planning relies on up-to-date information on biodiversity and I hope to start compiling a holistic picture of what False Bay looks like, and then determine how we can plan for its future. Creatures like rock lobsters, anemones and corals are my starting point – and, together with Sargasso, Jolene, my trusty field assistants and perhaps a little less Paul Simon, it seems I can start piecing together this rather complex ecological jigsaw puzzle.

A photo from the jump camera at 40 m. Learning to identify the species that are visible on these photographs is the next challenge and we will rely on some serious consultation with both South Africa’s invertebrate experts and many experienced divers in False Bay. Photo: Lauren De Vos (UCT and SAEON).