Travelling Trevallies

Giant trevallies (Caranx ignobilis) are no strangers to making headlines. These fish burst out of the waters in Seychelles, and into public fascination, on a sequence in BBC Earth’s Blue Planet II, sniping fledgeling terns from the sea’s surface. But their TV debut with David Attenborough came before that, swimming up the Mtentu River in South Africa to circle, and circle, and circle, in a mysterious aggregation captured on camera as “The Journey of the King Fish”. Now, the latest results from the Acoustic Tracking Array Project (ATAP) have confirmed that one of the largest aggregations of giant trevally in the world gathers in a marine protected area (MPA) off the Mozambican coast. This gathering is a predictable phenomenon, happening at the same place, and during the same season, every year. Before they aggregate each summer, these fish swim extraordinary distances of up to 633 km across an international border with South Africa. This, say the authors of the new study published this month in Marine Ecology Progress Series, makes it vital for Mozambique and South Africa to work together to manage an important fish population that cares little for our political borders.

Dr JD Filmalter prepares to release a giant trevally after fitting it with an acoustic tag. Photo by Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

How did the study happen?

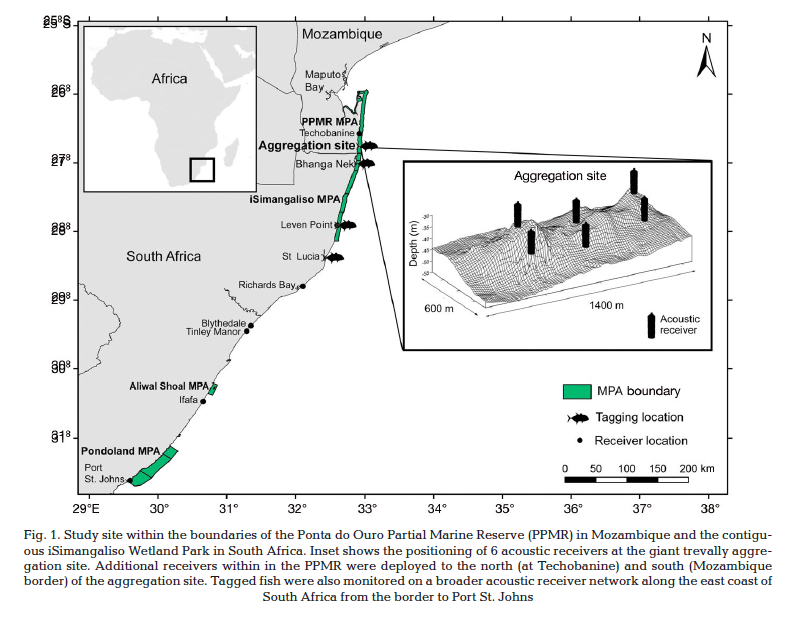

Ryan Daly, Clare Keating Daly and Paul Cowley, together with their co-authors from SAIAB and ORI in South Africa, and Centro Terra Viva in Mozambique, looked at the world’s largest known gathering of giant trevally in the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve (PPMR) in the Western Indian Ocean. They tagged 30 fish with acoustic tags and monitored their movement patterns over three years. Acoustic tags transmit a unique code, which is detected by a network of receivers when the tagged fish swims in the vicinity. The receivers log the fish’s unique code, the time and the date. All this information is downloaded later by researchers and used to map out the movement tracks of fish across this wide monitoring array.

“Acoustic telemetry research has gained immense popularity over the past two decades and the benefits of researchers working together, mainly by sharing data, has been witnessed all around the world”

explains Paul Cowley, who leads the ATAP project based out of Mkhanda, South Africa. “The philosophy of ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ has led to the establishment of collaborative research networks (like ATAP) in many places. Since its inception in 2011, the ATAP continues to show growth in terms of the number of animals (and species) being tagged, as well as the number of members”.

ATAP receiver and acoustic release at the water surface. Photo © Ryan Daly

This particular study relied on a network of six receivers distributed in the PPMR, a subtropical MPA that protects 98.5 km of coastline length from Maputo Bay in the north, to South Africa’s iSimangaliso Wetland Park in the south. Lead author Ryan attests to the PPMR’s current efficacy for fish populations, noting that: “It has some of the best-protected area governance in the region, with some of the best evidence for protecting its fish populations that I’ve witnessed in Mozambique”. Three receivers in Ponta Techobanine, and three receivers at the border with South Africa logged fish travelling both north and south of the identified aggregation site in the MPA. Collecting these data, and maintaining this network of receivers, relied on cross-border cooperation. “Currently, more than 30 scientists and their students from at least 14 organisations benefit from the ATAP’s network of receivers”, Paul continues. “This achievement would not be possible without support from the Canadian-based global Ocean Tracking Network and the National Research Foundation for equipment, and the Save Our Seas Foundation for funding to service and maintain the network of acoustic receivers spanning approximately 1400 km of coastline from False Bay to southern Mozambique”.

What did the researchers find?

Giant trevally showed what scientists term “site fidelity”: that is, they return to the same area each season, across multiple years. Often, this behaviour is linked to spawning, and it seems that this is what the trevally come to the relative sanctity of the PPMR to do each year. Paul and the team’s new insights into these huge predators highlight an important point: these fish swim the gauntlet across ocean areas managed by different countries, and management authorities, to do the most important thing for their population – reproduce.

“Besides the highly predictable aggregation of thousands of giant trevally at the same site and same time (season) each year, the remarkable distances covered by some fish was surprising because similar telemetry studies done on the same species in Australia and Hawaii never recorded such large long-shore movements, which in our study ranged over 600 km. This range covers the core distribution of this species in South Africa, which possibly means that all (or most) local (South African) adult giant trevally move to Mozambique each year to spawn”.

To try to understand a little more of what might help predict when, where and why the trevally choose to arrive in this region of Mozambique each year, the scientists measured other factors in the environment. They showed that the giant trevally aggregation was associated with rising sea temperatures and the full moon period, and that the fish seemed to aggregate more during the day.

What does this mean?

“The acoustic tracking of giant trevallies has yielded far greater insights into their movement patterns compared to the information obtained from conventional external dart tagging”, says Paul. “The highly predictable spawning aggregation makes them extremely vulnerable to fisheries. Hence, effective management measures are required to conserve this species”.

This study suggests that, given the numbers of fish that come to aggregate each year, most of the giant trevally population in the southwest Indian Ocean rely on the PPMR in Mozambique to breed. They, quite literally, put all their eggs into one MPA basket. If they’re returning each year to the same place, at the same time, that makes the trevally all too easy for fishers to find – a gathering that’s easy to deplete if fishing at that time is unregulated. The MPA is an important tool that could safeguard this population in the future, and there are few additional management steps that could strengthen controls for catching trevally. Currently, the giant trevally aggregate in what is called a “multiple-use zone” of the MPA, with the result that recreational fishing is allowed, as is some small-scale local community fishing (although this fishery doesn’t currently target the giant trevally aggregation). Paul summarises some of the recommendations outlined in the paper, noting that these few changes could further secure the future of this important fish population: “Reduce the recreational daily bag limit to 1 giant trevally per person per day, and propose a closed season over the aggregation period”.

Lead author Ryan Daly expands on these insights, noting the complexity required to achieve them: “The PPMR management has been doing an excellent job protecting the MPA’s marine resources, but this is a vast area that remains vulnerable to exploitation. Simply banning any remaining commercial fishing by the few licensed handline boats will further strain MPA management, requiring even more enforcement in the region with few resources. Going forward, we hope that the PPMR first receives more support to continue to monitor the MPA, before stricter controls are necessary. Improved regulations, such as a closed season for giant trevallies in the PPMR when they are most vulnerable (during aggregation season), will improve the effectiveness of the MPA for these fish”.

Researchers (from left to right) JD Filmalter, Paul Cowley and Ryan Daly. Photo by Clare Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Where to from here?

The study highlights why we need to navigate effective transboundary management better – but might the results (and recommendations) for giant trevally be a blueprint for principles that can be applied to other large, mobile or transboundary marine populations on this same section of coast? On this point, Paul raises the need for continued monitoring and the expansion of the ATAP network: “Many South African marine species, including bony fishes, sharks, whales, dolphins and turtles, undertake transboundary movements. More information on the extent of these movements and the timing of migrations for each species is required for species-specific management recommendations. The giant trevally example may be unique in that they form a predictable seasonal aggregation that allows for site-specific recommendations to be made. There are plans to deploy more receivers and tag more mobile species along this section of the coast”.

As for where the trevally travel when they’re not spawning in Mozambique – well, that’s a question for the near-future for Paul and the team. “The monitoring and tagging of giant trevallies are ongoing, and our research team has tagged more individuals at another aggregation site (the Mtentu Estuary in Transkei). We are also tagging more individuals in Mozambique (at Bazaruto Island and Vamizi). The vision is to gain a better understanding of the behaviour of several spatially discrete populations and examine the level of connectivity between populations in SA and Mozambique.” For those trevallies that traverse the coast and cross the border each summer, Paul’s hopes remain high:

“Our research team has a good working relationship with the Ponta do Oura Partial Marine Reserve, and we are confident that the recommendations from this research will be taken seriously”.

You can follow ATAP on Twitter: @ATAP_ZA

You can read the paper here.

**Reference: Daly, R., Filmalter, J.D., Daly, C.A., Bennett, R.H., Pereira, M.A., Mann, B.Q., Dunlop, S.W. and Cowley, P.D., 2019. Acoustic telemetry reveals multi-seasonal spatiotemporal dynamics of a giant trevally Caranx ignobilis aggregation. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 621, pp.185-197.