The road to CITES

CITES COP19 was a landmark moment for shark and ray conservation. But bringing 90% of the fin trade under regulation was never going to be easy. Behind these historic CITES listings is a story of perseverance, collaboration and hope.

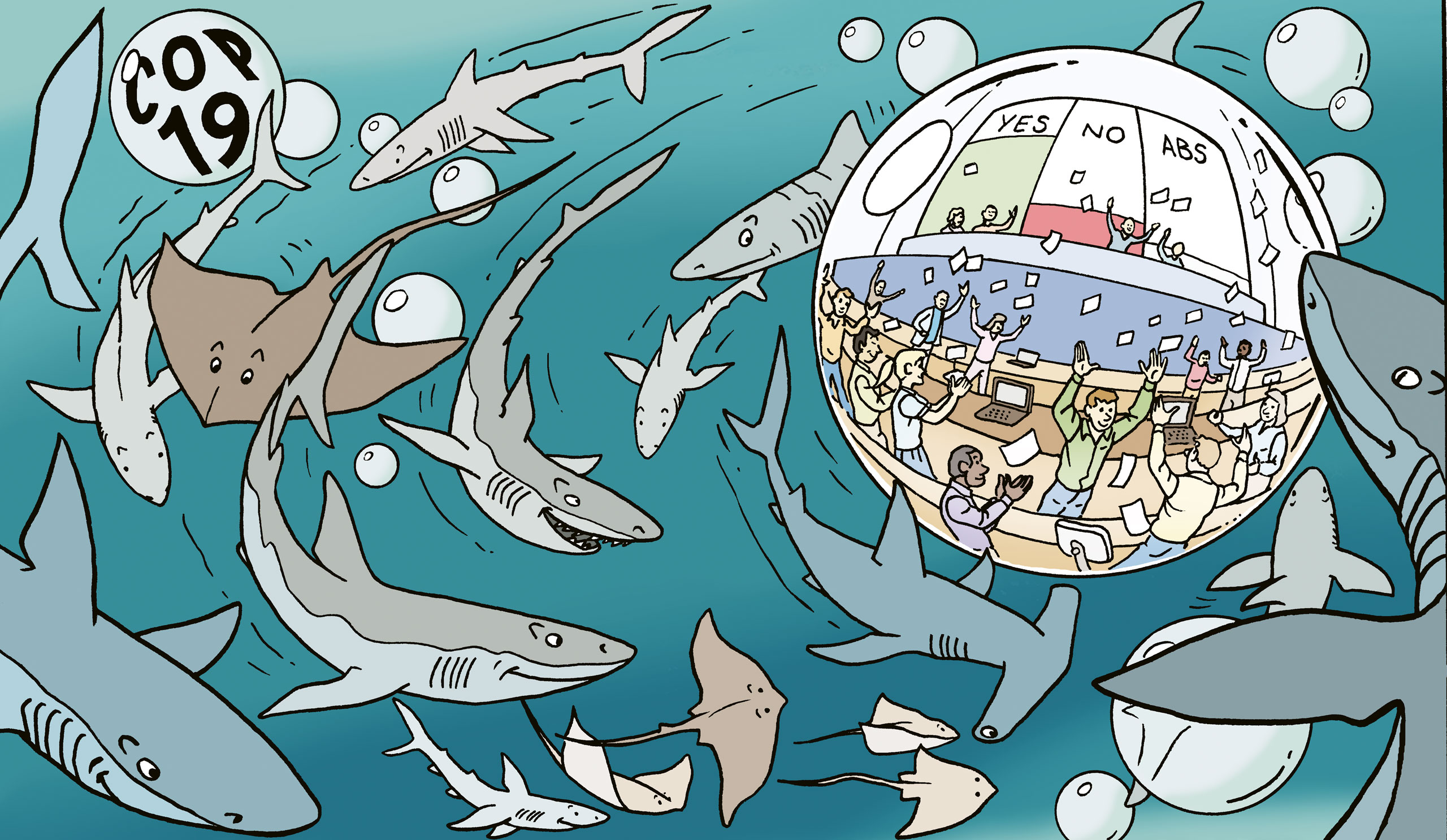

It was a moment of unity. Scientists, conservationists, policy-makers, NGOs, practitioners and activists, scattered across time zones and continents, all watching a large conference room in Panama City. There, parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) were deciding by anonymous vote on one of the most ambitious proposals for sharks and rays to date – one that, if passed, would regulate almost all of the shark-fin trade. Some, like me, had stayed up late to watch the livestream, bent over phone and laptop screens. Others were in the room itself, shrouded in a heavy silence. One attendee sent round a picture of their smartwatch displaying an impressive heart rate of 146 beats per minute.

To say this was a significant moment for shark conservation would be an understatement. For years, numerous individuals, organisations and governments had worked tirelessly to overcome opposition, scepticism, and many political, cultural and economic barriers to protect some of the most traded shark species in the world. More than a decade of hard work, condensed into a nail-biting few minutes.

Suddenly the blank screen we had all been watching glitched and, collectively, the entire shark conservation community held its breath. Then, the result: 88 yes, 29 no, 17 abstain. An overwhelming majority in favour of bringing the fin trade under regulation – the half-billion-dollar industry that has been instrumental in bringing many species to the brink of extinction. Instantly the room erupted in a not-so-successful attempt at silent celebration, cuddly toy sharks proudly held aloft. And messages of joy and pride rippled across social media as the news reached those of us at home.

‘It was a huge relief!’ says Luke Warwick, director of the Sharks and Rays Program for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an organisation that had been a driving force behind the ambitious proposals.

The journey to this moment started a long time before the 2,500 delegates gathered in Panama for the 19th ‘World Wildlife Conference’. CITES – an international agreement between governments to regulate trade in endangered species – had officially come into force in July of 1975, but it wasn’t until 40 years later that sharks and rays began to trickle into the Appendices. At that time, scientists lacked the data to sufficiently support proposals to include many commercially traded species. The political environment was also unfavourable. International trade in shark products was, and still is, highly lucrative. Many parties to CITES had a vested interest in seeing trade continue without oversight and did not yet face the public pressure to protect sharks that we see today. ‘The general consensus 10 to 15 years ago was that few, if any, sharks and rays could be CITES-listed,’ Luke recalls. ‘Full regulation of the around 100 species that comprise the shark-fin trade seemed all but impossible.’ Securing such protections for sharks would require significant resources, dedication and, above all, the enduring belief that one day the tide would turn.

Illustration © Rêgric

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

A glimmer of hope came in 2013, when the first commercially traded shark species were listed on Appendix II. This included the oceanic whitetip shark, formerly one of the world’s most abundant species before demand for their fins drove populations into freefall. This, Luke feels, set the wheels into motion. ‘Following those first listings, a wide range of governments, groups and individuals worked together to ensure they were effectively implemented, while pushing to build on them.’ Momentum continued to grow, and at CITES COP18 in Geneva, Switzerland in 2019, the addition of shortfin and longfin mako sharks, wedgefishes and giant guitarfishes, brought almost a quarter of the fin trade under regulation. It was significant progress, at least from a political standpoint. But, with new science indicating global shark and ray populations were still plummeting, there was little time for pause. Even stronger and more comprehensive regulations were needed.

Looking three years ahead to CITES COP19, several ocean-minded governments, working together with the WCS, Shark Conservation Fund (SCF) and leading shark scientists, began to circulate a bold plan to regulate the remainder of the shark-fin trade. They were met with considerable scepticism. It was ambitious: a proposal to list the entire family of 56 requiem shark species, one of the largest and most traded families of sharks in the world. Additionally, all six small hammerhead species and the remainder of the guitarfish family would be included. This would require substantial work and resources. Each proposal would need to demonstrate, using robust scientific evidence, that trade sufficiently threatened the very survival of the species in question.

Luckily, science had advanced rapidly since the first shark listings. ‘The proposals that moved us from 25% to more than 90% of the shark-fin trade being regulated were made possible by focused scientific research,’ says Luke. ‘The wealth of information provided by the updates to all shark and ray IUCN Red List assessments was crucial, along with innovative studies that used underwater cameras to survey reef shark populations, and genetic techniques used to uncover the composition of the shark-fin trade at its hub in Hong Kong.’ But collating all the scientific evidence was only part of the battle. This was a political arena. Those who made the final decisions were not shark scientists and conservationists; they were world leaders, representing countries and regions with vastly different interests and socio-economic backgrounds. Getting the proposals over the line would also require a sophisticated global campaign to persuade those in power that protecting sharks was not only in their best interests, but essential for our future.

Blue sharks are the most heavily fished shark species in the world but will now be listed along with the rest of the requiem shark family. Photo © Simon Hillbourne

A TEAM EFFORT

Despite the initial push-back, SCF and WCS forged ahead, and along with the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, Oceans 5 and the Flotilla Foundation, worked to provide resources for a global campaign to drum up political and logistical support for more comprehensive global trade regulations for sharks and rays. A significant part of this involved developing tools to demonstrate how these listings could be implemented.

Equal effort went into public communications. Although the public do not vote for species to be CITES-listed, their voice matters for those that do. Governments will inevitably want to stay on the right side of their constituents, and so getting the public behind protections for sharks could influence political support for the proposal. As part of the SCF, the Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF), along with the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), Blue Resources Trust, Humane Society International and WCS, worked hard on an ambitious communications strategy for the lead-up to COP19. This included infographics that broke down the four biggest research papers of the last decade, showing how international trade had impacted sharks worldwide and why this mattered. They also explained the case for adding the entire family of requiem sharks, linking them to the shark-fin trade.

As COP19 drew closer, there was cause for cautious optimism. Conference hosts – the Government of Panama – championed the proposal for requiem sharks, which was then co-sponsored by 40 other countries. They also co-sponsored the proposal for small hammerheads, which was championed by the European Union. On the day itself several desks proudly sported plush sharks and some delegates had even arrived in shark attire. All promising signs – but they still had to get past the other governments in attendance, some of whom directly opposed the proposals. But against the odds, parties voted in favour of adopting both proposals and at a plenary session the following week, they were formally adopted. It was a big win for those who had fought determinedly, against all the odds, to achieve the impossible.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

It was a long road to CITES COP19 – but the work doesn’t stop there. ‘The listings represent the end of the first phase of shark conservation, which was to establish strong drivers for domestic shark conservation,’ Luke explains, ‘but without follow-up, they won’t help save species from extinction. Work will now focus on implementation.’ Customs and border officials will now require training in the use of genetic and visual tools to identify illegally traded products, and in the preparation of new procedures and documentation to ensure that catch and trade is sustainable. In respect of the challenges ahead, CITES has already amended its allotted time for countries to get everything in order. All countries must be ready to implement the new trade regulations in 12 months – 2023 will be a very busy year for some!

But for now, Luke – and the many others who worked so hard to bring this to fruition – can pause to reflect, and celebrate. ‘The fact that transformative action was possible within a decade is incredible,’ smiles Luke. ‘And that is the level of ambition we need to take into the next phase of shark conservation if we are to save these ancient predators from extinction.’