The IUCN’s report on the global status of sharks, rays and chimaeras: a crisis, but there are solutions

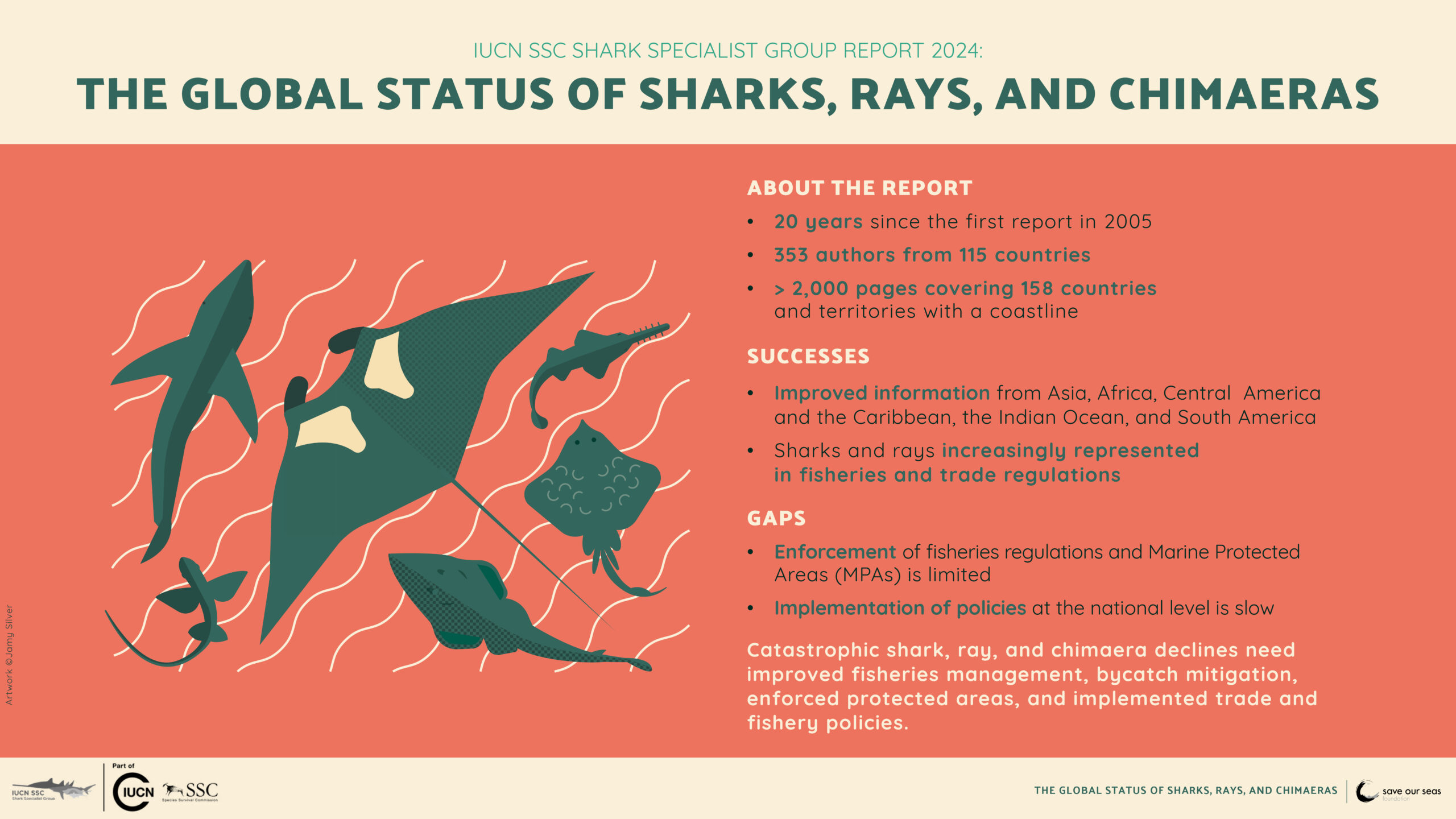

Sharks, rays and chimaeras are overfished and heading for extinction. More than 300 scientists have published 20 years of data in a landmark global report that details the biology, fisheries, trade, conservation efforts and policy reforms for these marine animals across 158 countries and jurisdictions. It’s a global wake-up call: we need to address overfishing and bycatch – and urgently. But there is also hope. We have the information to hand, and the dedication of so many has brought us to a historic moment when we can steer towards sustainability.

Twenty years ago, the small number of people who then comprised the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (SSC) Shark Specialist Group (SSG), sounded the alarm: sharks and rays were in increasing demand for the growing fin trade, and they needed to be on the conservation map. Today, the SSG has published its update in the form of a 2,000-page report that reflects the scale of change in two decades of marine science and conservation – and in the status of sharks, rays and chimaeras.

‘In nearly 20 years since the first status report on sharks, rays and chimaeras there have been drastic changes, with this species group becoming one of the most threatened vertebrate groups on the planet,’ says Alexandra Morata, her concern palpable. Her efforts as an IUCN programme officer have focused on helping to coordinate the report, together with a strong cohort of scientific editors. ‘This report showcases in great detail the past, present and future conservation efforts dedicated to sharks, rays and chimaeras at the regional and, especially, the national level. It covers more than 150 countries and overseas territories and has over 350 contributors from around the world. Beyond the “doom and gloom”, there have been Herculean efforts that have led to today’s success stories.’

The report on the global status of sharks, rays and chimaeras represents lifetimes of work by a dedicated cohort of scientists and conservationists. They have pushed shark research, policy and conservation efforts from relative obscurity historically to where we stand today – equipped with information at a country-by-country level of detail for 158 countries and jurisdictions.

Blue sharks near Azores, Portugal. Photo © Simon Hilbourne

‘This report provides evidence of how overexploitation is impacting shark, ray and chimaera populations around the world. It showcases how our actions as humans are jeopardising the future of these species,’ says Dr Rima Jabado, the IUCN SSC deputy chair and SSG chair who led the 2024 report. As the driving force behind this historic publication, she has witnessed at first hand the wealth of knowledge, passion and dedication that exists in the shark conservation field. ‘It also reflects the tremendous dedication of scientists, researchers and conservationists who are working as a community to contribute to conservation and make a lasting change. But the message is clear: with the precarious state of many of these species, we can’t afford to wait. The report is a call to action so we can work together and make each of the country recommendations a reality, especially those that relate to responsible fisheries management. It is the only way these species will survive and continue to thrive in aquatic ecosystems.’

Infographic by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

What has changed in 20 years?

The publication of the SSG’s first report, Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: the status of the chondrichthyan fishes, in 2005 heralded a sea change for these species, whose obscurity in policy, conservation and fisheries management at the time was a serious concern; the pace of their declines threatened to outstrip our information about – and attention to – them.

Sarah Fowler, a scientific adviser to the Save Our Seas Foundation (SOSF), led the publication of the 2005 report and contributed to the latest version. ‘At that time’, she explains, ‘the conservation of sharks and their relatives had a very low profile in international bodies.

‘We wrote two pages on CITES (the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species) because it had recently begun to discuss sharks and quite a lot was happening. We also wrote a page on the FAO’s relatively new International Plan of Action for Sharks; otherwise, there was not much to report. Even so, I recollect having to update the text before publication, as the impetus for international shark conservation and management policy grew, including the first listings of sharks in the CITES Appendices and the CMS (Convention on Migratory Species).’

Whale sharks and basking sharks made it as the first species to be regulated by CITES on Appendix II, a move that recognised, for some large and charismatic species at least, that there were very real biological and ecological limits to our harvest of their populations; a harvest that had previously been relatively unrestrained. Rays – and certainly chimaeras – however, remained off the radar for some years yet, and the effort to recognise commercially important shark species, at the very least, would have to remain high in the ensuing two decades.

‘Moving on to the new status report, you might expect me to say that the updated chapter on international conservation and management initiatives has grown hugely,’ resumes Sarah. ‘But that’s not true at all. The chapter is much shorter. The main reason for this is the internet. We now have huge resources at our fingertips and there’s far broader awareness of the importance of international and regional treaties. Such a lot has now been written on the subject that there’s very little point in repeating it, particularly when policy develops so rapidly.

A bowmouth guitarfish, listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. Photo © Byron Dilkes

‘The challenge for me, this time around, was changing the structure. I wasn’t happy with the way in which, more than 20 years ago, I had accepted how conservation and management policy for sharks as fisheries resources, as opposed to sharks as wildlife, were discussed in completely different, and indeed sometimes combative, sectors. Our chapter had reflected this, describing fisheries and biodiversity agreements in separate sections. That was a mistake!’

Explaining further, Sarah says, ‘The conservation and management of sharks is difficult for many reasons, including their slow life-history characteristics and their capture in multi-species fisheries, which is why it’s important for managers to use every policy tool available and make the most of cross-sector cooperation and the synergies between them. For example, high-seas shark fisheries are managed under fisheries instruments that may prohibit landings of threatened species or may set quotas, but CITES provides the framework for ensuring that these high-seas species are certified as legal and sustainable and can be traced from fishery to consumer country. CMS, which was developed to encourage the collaborative conservation and management of migratory birds and mammals and their habitats as they move between range states, is equally appropriate for the collaborative management of shared fish stocks.

‘These “fish” and “wildlife” silos still exist, but many governments are working on breaking them down to improve the conservation and management of fisheries,’ she concludes. ‘Although there’s still a lot to do, I like to think that sharks have, in some respects, led the way.’

Most apparent in the 2024 report is the increase in the range of research topics. We are investigating a greater diversity of species, and attention is being trained on emerging threats (habitat degradation and loss, pollution in a variety of forms from plastics to noise and oil, and deep-sea mining) and the accelerating global changes to aquatic ecosystems. The diversity of researchers who contribute to science and conservation within the SSG network and beyond has also grown, as readers can appreciate in the level of detail available for the 158 countries, which are grouped into 10 (arbitrary) geopolitical regions.

What do we know about sharks, rays and chimaeras?

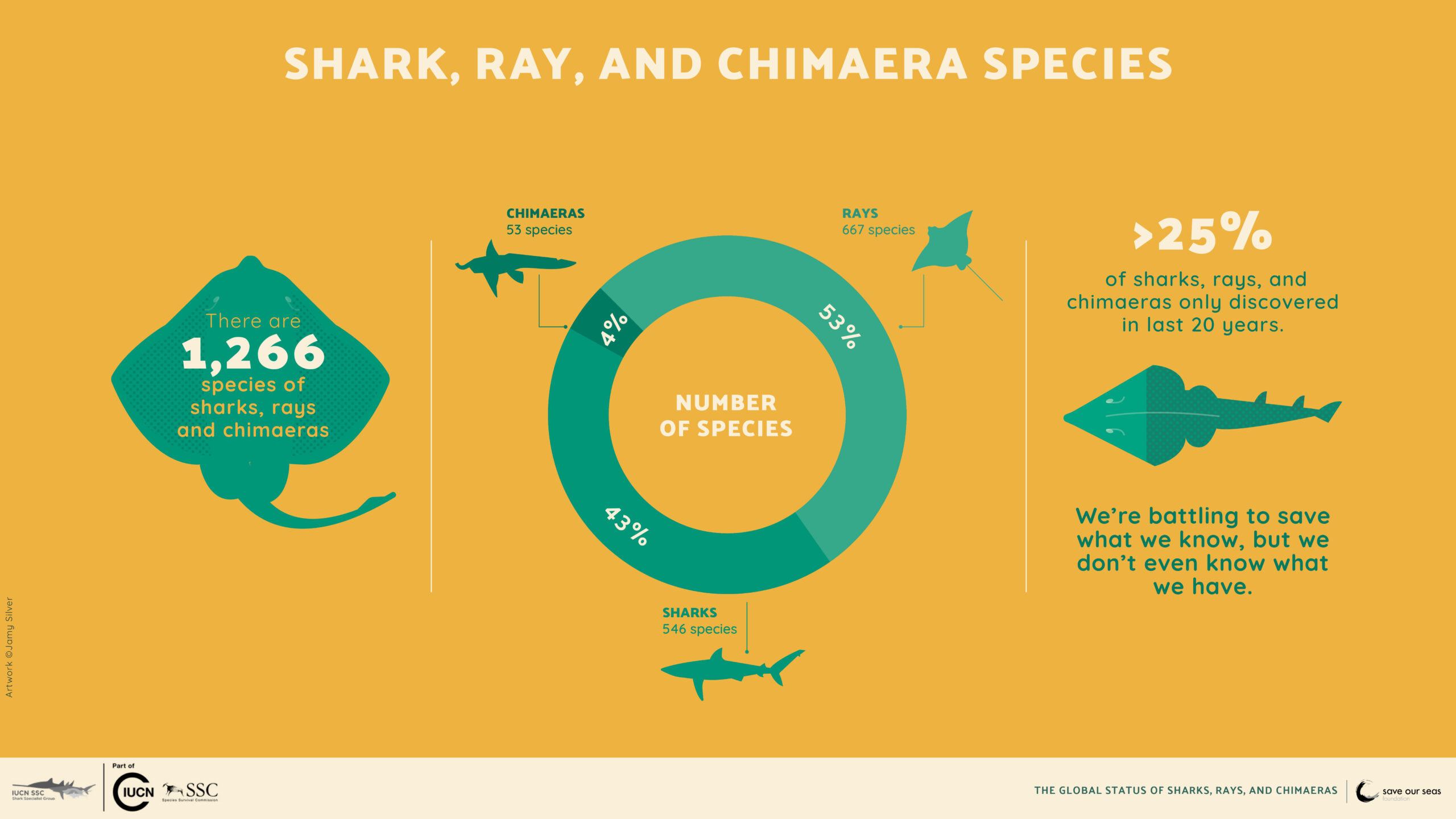

Our understanding of the diversity of sharks, rays and chimaeras has been revolutionised over the course of the past two decades. Of the 1,266 species that have been described to date, more than 340 have been described since 2001. Classifications are constantly being amended by taxonomists as new data become available, and advances in DNA-sequencing technology have changed the game. This information revolution is possible thanks to collections in new locations, habitats and depths; the implementation of new sampling gear; and global scientific collaborations. But taxonomy needs more support, with funding and skills development to secure its future.

Infographic by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

‘The availability of accurate and comprehensive information is key to informing the sustainable management of species, including chondrichthyans,’ says Dr Sally Sinclair from the University of Göttingen. ‘Sharks, rays and chimaeras face a range of threats that need to be addressed through concerted management and conservation actions to secure positive outcomes for these species and the communities relying on their ecological and economic roles. This report provides a comprehensive resource that amalgamates experts’ understanding with the most up-to-date information available on the study of this group across the globe. It is a go-to reference point of current knowledge that can be used by those in positions to improve conservation outcomes and by anyone who is simply interested in learning more about this group.’

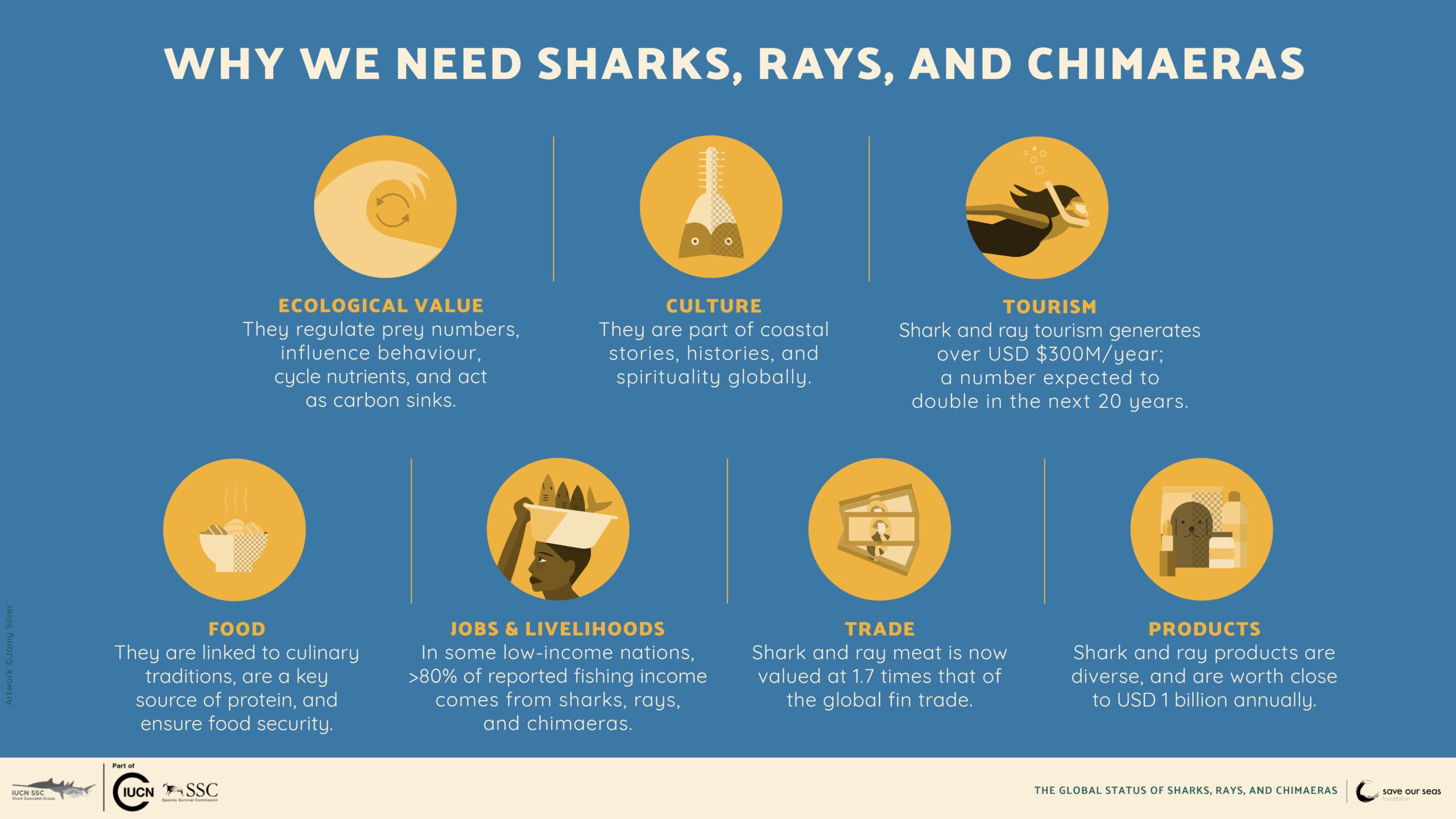

The report also reflects our shift in understanding of the ecological role that these species play in aquatic ecosystems. There is still very little known about the ecological role and life histories of sharks, and the information we do have comes from a small number of well-known species. Since the 2005 report, access to the oceans and the diversity of habitats and oceanographic conditions in which sharks, rays and chimaeras live has improved as the concurrent diversification in technological tools enables us to investigate them more critically in their diverse forms and ecological roles. For a long time, scientists assumed that sharks were essential to marine ecosystems because they are (generally) large predators that regulate populations of their prey; in ecological-speak this is known as ‘top-down’ forcing. But new reviews of the ecological importance of sharks point out that this greatly simplifies the contribution played by the diversity of sharks and rays that inhabit all manner of ocean niches and play varied roles in our oceans.

As predators, sharks regulate prey numbers. But they also influence prey behaviour: tiger sharks create a ‘landscape of fear’ that keeps their green turtle prey rotating their grazing areas in sea-grass meadows so that no single patch is overgrazed. And that’s crucial for us because sea grass is a carbon storage superstar, absorbing the excess atmospheric carbon that has a heating effect on our planet and therefore buffering us from the worst effects of our changing climate. Sharks cycle nutrients between different depths and habitats, feeding in habitats far away and returning to coral reefs, estuaries or mangroves. This may mean that they transport nutrients between habitats, potentially helping to fertilise coral reefs and ocean plants. Primary producers like phytoplankton, kelp, sea grasses and other ocean plants are the life-giving oxygen for the lungs of our planet; by providing them with fertiliser, nutrient-transporters like sharks help to maintain the very breaths we take.

Infographic by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Dr Ana Paula Barbosa Martins from the Ocean Frontier Institute at Dalhousie University in Canada reflects on how the 2024 report updates the breadth and scope of everything we know about sharks, rays and chimaeras. ‘Historically, scientific knowledge about sharks and rays has been limited to a few regions and species,’ she says. ‘This report’s greatest achievement is its comprehensive portrayal of the diverse ecological, socio-economic and cultural roles that sharks and rays play around the world. The report underscores the need for a multidisciplinary and global approach to shark and ray conservation, emphasising the importance of collaboration among governments, academia, industry and the public.’

The socio-economic, cultural and ecological importance of sharks, rays and chimaeras

Our lives our intertwined with the health of shark and ray populations. They have captured our imaginations throughout history; they also keep food on plates, create jobs and income and maintain functioning ocean ecosystems. They are protected, fished, traded, consumed or used as part of the culture of many nations, and are a key component of coastal livelihoods in many countries.

Feared and revered, sharks are part of coastal stories, histories and spirituality around the world. Shark teeth were used by the Mi’kmaq people of eastern Canada for burials and rituals. Indigenous Hawaiians have documented the ecological relationships between sharks and their environment through stories and chants, and many ethnic groups in West Africa also have spiritual connections to sawfish.

More than one million people have joined shark diving and snorkelling tours annually in over 40 countries, focusing on about 50 shark and ray species and generating in excess of US$300-million a year; these figures are expected to double in the next 20 years. Connecting people to sharks, through recreational angling, dive tourism or public aquariums, is a key part of conservation.

Sharks and rays come in all manner of shapes and sizes and inhabit almost every part of the ocean. Their diversity means they play a variety of important ecosystem roles. We need sharks, rays and chimaeras. We are only beginning to decipher the role they play in delivering the life-supporting resources that scientists call ecosystem goods and services: the provisions (like food and water), the regulating processes (like carbon storage and storm surge buffering), the cultural values (like recreation spaces and spiritual meaning) and the support (like phytoplankton blooms that underpin the world’s major fisheries) that allow us to survive and thrive on this planet.

Our reliance on sharks, rays and chimaeras for our survival as human beings is ancient and complex – and continuously evolving. What we do know is that we will need to end the declines of sharks, rays and chimaeras to help us to navigate the climate and biodiversity crises.

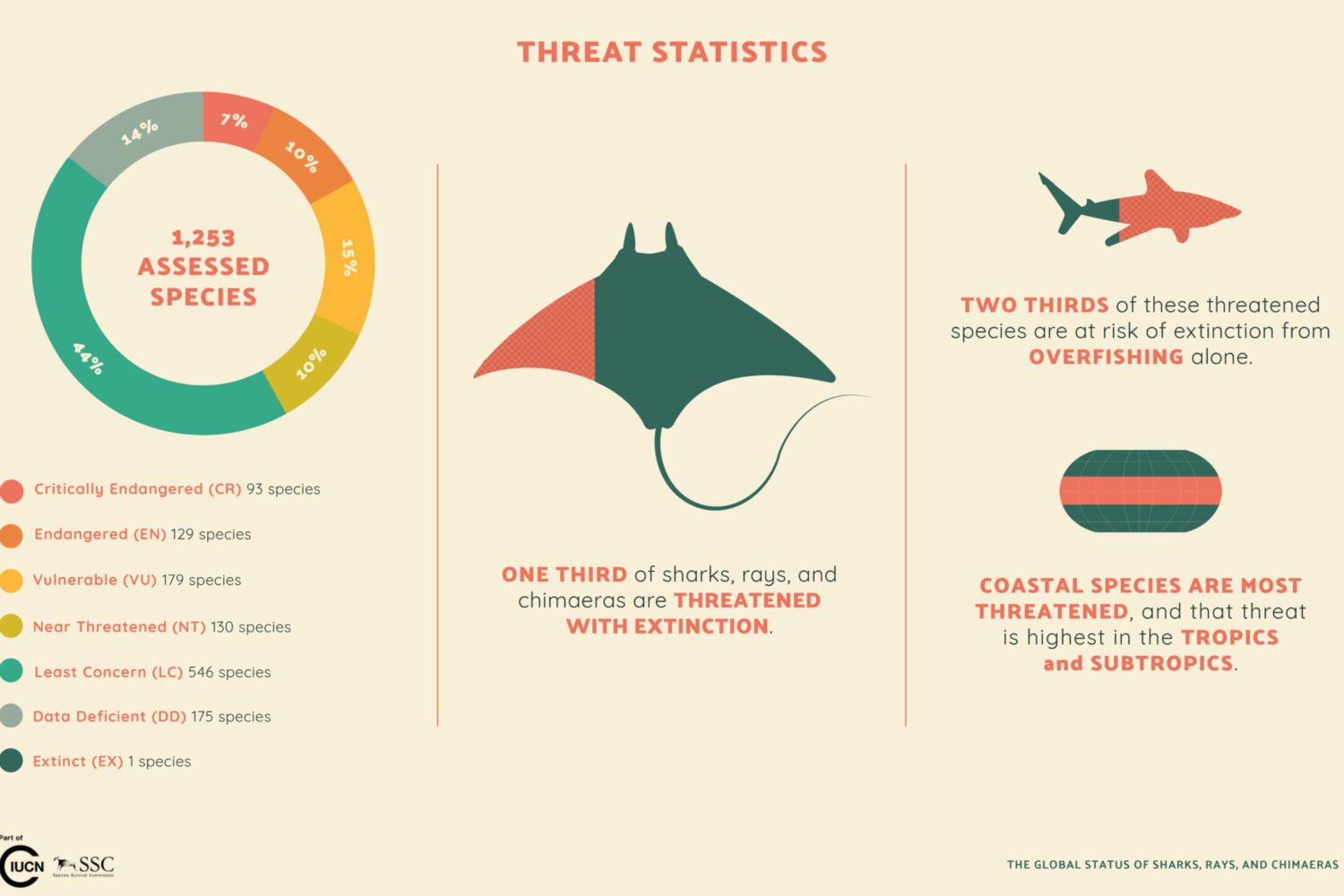

Sharks, rays and chimaeras are overfished and heading towards extinction

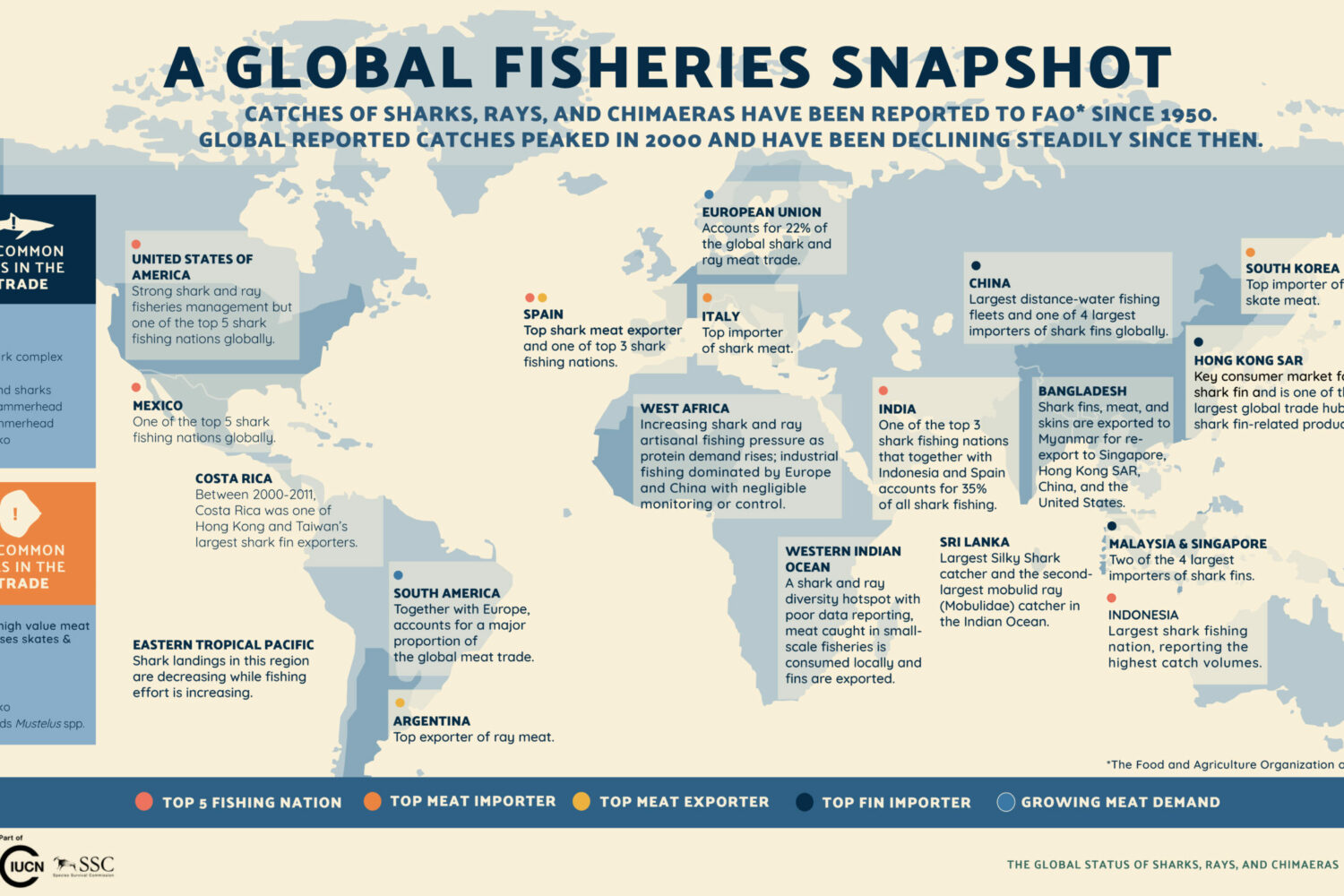

Overfishing is driving most species to extinction. Indonesia, Spain and India are the world’s largest shark-fishing nations, with Mexico and the USA making up the top five shark catchers. But only 26% of species globally are targeted; most are caught (and retained) as bycatch. Huge population declines have been seen in the rhino rays (such as wedgefish), whip rays, angel sharks and gulper sharks.

The global reported shark meat trade has increased from US$157-million in the early 2000s to US$283-million in 2016. Shark and ray meat is now valued at 1.7 times that of the global fin trade. Spain and Italy are the top importers and exporters of shark meat, with the EU accounting for 22% of global shark meat trade and South America sharing in the rising demand. Argentina and South Korea are the top global importers and exporters of ray meat respectively. And in many low-income countries, shark and ray meat of a diversity of species equals food security.

‘With sharks and rays under such threat globally from overfishing, there is a critical need for conservation action, policy reform and making fisheries sustainable. Yet all of these rely on good information,’ says Dr Rhett Bennett, who works for the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Western Indian Ocean shark and ray programme and is a regional member of SSG Africa.

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, half of all coastal species are at risk, and the threat is highest in the tropics and subtropics. This imperils the functioning of ecosystems on tropical coasts. The Java stingaree, the Red Sea torpedo ray and the lost shark are considered possibly extinct (each last seen in 1868, 1898 and 1934, respectively).

‘Developing countries, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, represent the intersection of particularly high fishing pressure, dependence on fisheries for livelihoods and limited access to scientific information, all of which make the publication of all types of available information that much more important in order to support conservation and management,’ says Rhett. ‘This report brings together scientific information and the collective knowledge of hundreds of experts from around the world about the biology, ecology, fisheries, trade, threats, policy and other aspects pertaining to sharks and rays. It is arguably one of the most comprehensive reports on a group of species to date. Governments, scientists, conservation practitioners, educators and other stakeholders are encouraged to use and draw from the report as a reference and guide in the important work they are doing to improve the conservation status of sharks and rays around the world.’

But is there hope, and what are the solutions?

Infographic by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

The IUCN report outlines clear steps at a country-by-country level to halt the decline of sharks, rays and chimaeras in 158 countries and jurisdictions. Sustainable fisheries management tops the list; in almost every case there is a need to improve stock assessments, to support and include local communities and to regulate fishing practices to minimise bycatch. More marine protected areas would also go a long way towards protecting essential habitats for sharks, rays and chimaeras, which they need to recover from overfishing and to rebuild population resilience to adapt to our changed climate. Stronger law enforcement within these protected areas is also required once they have been declared.

Policy is improving; more than 140 species are now regulated by CITES to curb unsustainable and illegal wildlife trade, but these regulations must be implemented effectively at national level to be truly effective. We need to call on our governments for immediate action and accountability. Funding bodies need to focus on allocating more resources to combating illegal and excessive fishing and to improving the quality of data being reported to fisheries in almost all countries on earth. And we can support efforts to build resilience in vulnerable communities that are hardest hit by biodiversity loss and climate change.

Each region faces unique challenges in protecting sharks, rays and chimaeras. Access to remote areas, especially across Africa, has increased scientific understanding of the scale of exploitation. Knowledge has improved significantly in Asia, Africa, Central America, the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean. There are also hopeful instances of sustainable fisheries in Canada, the USA and Australia. There have been incredible strides in research and policy, but this hard work will only save species from extinction if the report’s recommendations are implemented nationally.

‘This report provides the most in-depth overview of shark, ray and chimaera fisheries, trade and conservation management to date,’ says Dr Michael Grant, a Save Our Seas Foundation project leader based at James Cook University and a regional member of the IUCN SSC SSG’s Oceania Group. ‘It offers a resource for scientists, managers and policy-makers to easily access up-to-date information on shark, ray and chimaera management across a range of nations, and for comparisons to be made between fisheries, trade and management initiatives across these nations.’

A global fisheries snapshot

The global status of sharks, rays, and chimaeras

Read the full report here: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/52102

Read the full report here: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/52102

EDITOR(S):

Rima W. Jabado, Alexandra Z. A. Morata, Rhett H. Bennett, Brittany Finucci, Jim R. Ellis, Sarah L. Fowler, Michael I. Grant, Ana P. Barbosa Martins, and Sally L. Sinclair