The Depths Awaken

The Weird and Wonderful Sharks from Earth’s Own Inner ‘Space’.

The 4th is strong with this one! Today, we’re bringing you back to earth to celebrate the alien-looking creatures that roam the depths of our oceans.

Many believe that we know more about outer space than we do about our ‘inner space’ – our oceans. What we do know, is that there are some pretty radical creatures living down there.

So, in honour of a galaxy far, far away, we’d like to celebrate the weird and wonderful sharks from Earth’s own inner ‘space’.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Velvet Belly Lanternshark

These are not the sharks you’re looking for: the velvet belly lanternshark (Etmopterus spinax) is a master of the mind trick. Light-producing cells on the belly allow this species to pass undetected as it cruises the mesopelagic zone (200-1000m). Glowing in the dark might seem like an odd way to hide, but because some light reaches these waters from the surface above, a bright underbelly helps conceal the shark’s silhouette from any prey swimming beneath it.

The tactic, known as ‘counterillumination’, is common in many species that inhabit this slice of the water column. But in 2013, scientists discovered something peculiar: these sharks have glowing regions on their backs as well. A closer look revealed this second set of lights coincides with an array of defensive spines. The built-in laser swords glow and are most visible to would-be predators, suggesting they might serve as a warning beacon – a way to say, ‘you can eat me, but it’s going to hurt.’

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

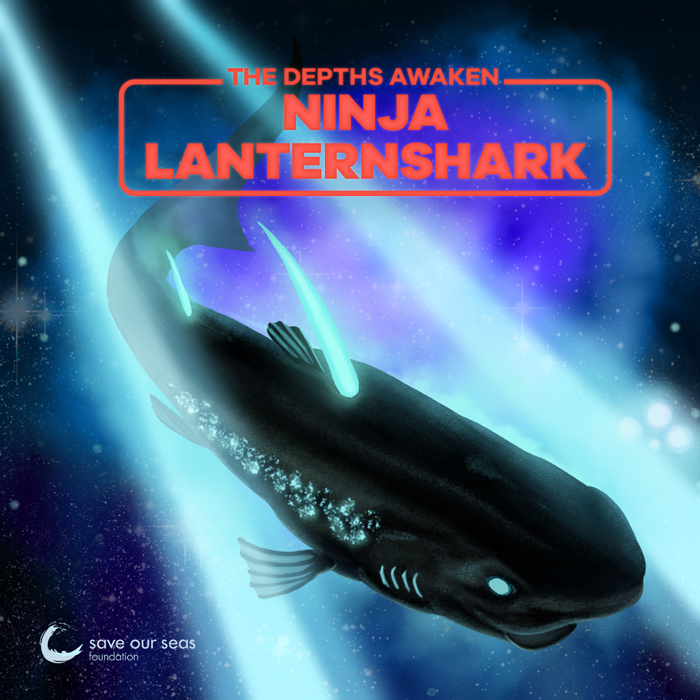

Ninja Lanternshark

The ninja lanternshark (Etmopterus benchleyi) might share a Dark Lord’s fashion choices, but don’t let that jet-black skin fool you. There’s nothing sinister about this pint-sized predator. First spotted in 2010 off the Pacific coast of Central America, the ninja lanternshark measures just 0.5 meters (1.5ft) in length. These sharks share the cloaking abilities of their close kin, but the species’ signature glow may be dimmer than that of other lanternsharks. Dawning a dark-side ensemble may help this master of stealth sneak up on its prey. The shark’s scientific name is a nod to Jaws author Peter Benchley.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

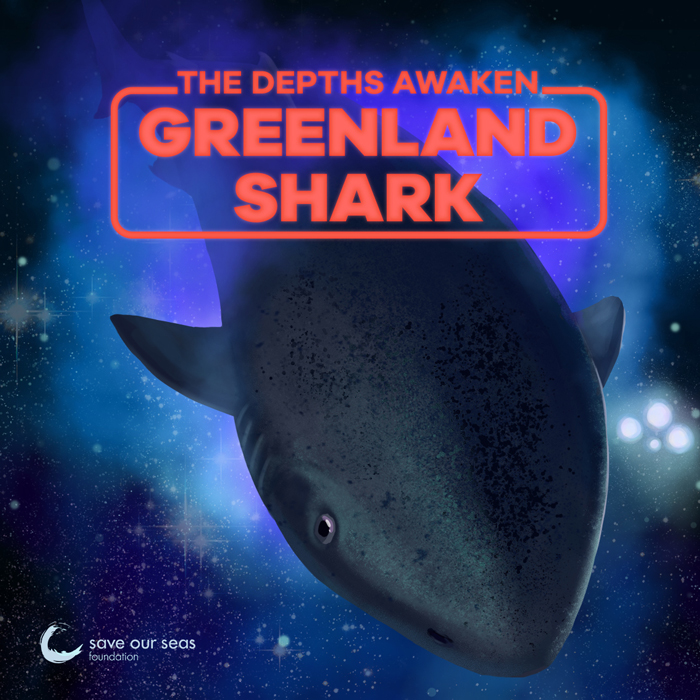

Greenland Shark

Reaching lengths over six metres, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is one of the largest living shark species. A knack for hanging out under seasonal sea ice, however, makes this giant particularly elusive. The animals prefer the chilly waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans, and while tauntauns might be off the menu, Greenland sharks do occasionally snack on polar bears. Most adult Greenland sharks are effectively blind, thanks to pesky copepod parasites that cling to their eyes. But successful sightless hunting isn’t this species’ only claim to fame: these cold-water creatures are among the longest-lived vertebrates on Earth. Growing just one centimetre per year, it’s estimated that the Greenland shark only reaches sexual maturity at 150-years-old.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Goblin Shark

Escaping the extendible maw of the goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) is about as easy as breaking out of a garbage compactor – if you happen to be a bony fish, squid, or crustacean. This deep dweller’s jaws protrude faster than those of any other shark species. In fact, at 3.1 meters-per-second, goblin sharks strike more quickly than most cobras. Flabby muscles and a mushy skeleton – which earned this ‘ghoulish’ shark its common name – mean goblin sharks are slow swimmers. In the deep sea, where calories are hard to come by, energy savings outweigh the need for speed. Goblin sharks won’t be running spice anytime soon, but the species’ signature slingshot likely makes up for its poor swimming ability.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

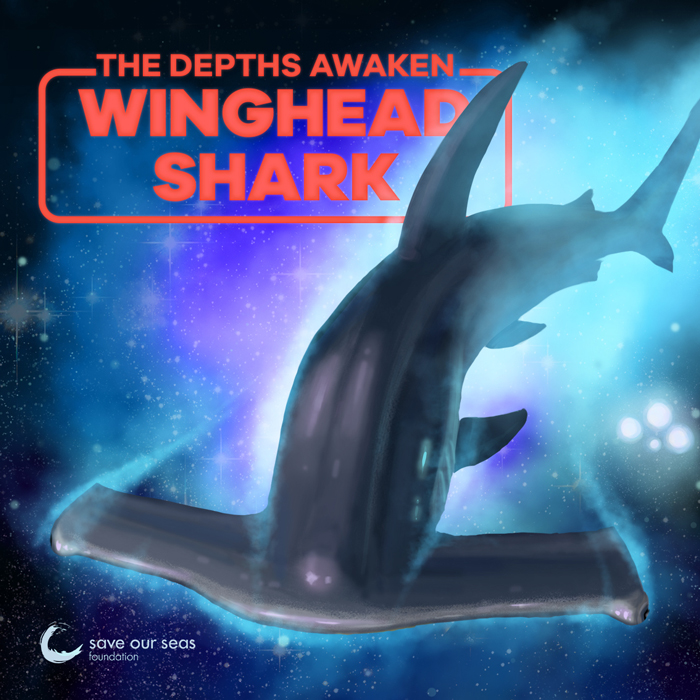

Winghead Shark

Shark five standing by! The winghead (Eusphyra blochii) isn’t a deep dweller, but this endangered, coastal species could outmanoeuvre the best starfighter pilot. With their high speeds and quick turns, Hammerheads are known as the ‘Ferraris of the sea’. Despite being one of the smallest members of the group, the winghead boasts a front end that’s nearly 50 per cent the length of its body. The reason behind this supersized cephalofoil remains somewhat unknown, but it may enhance the winghead’s turning radius during hunting. Another theory suggests that having expanded, separated nostrils gives the shark’s sensory system a power-up.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

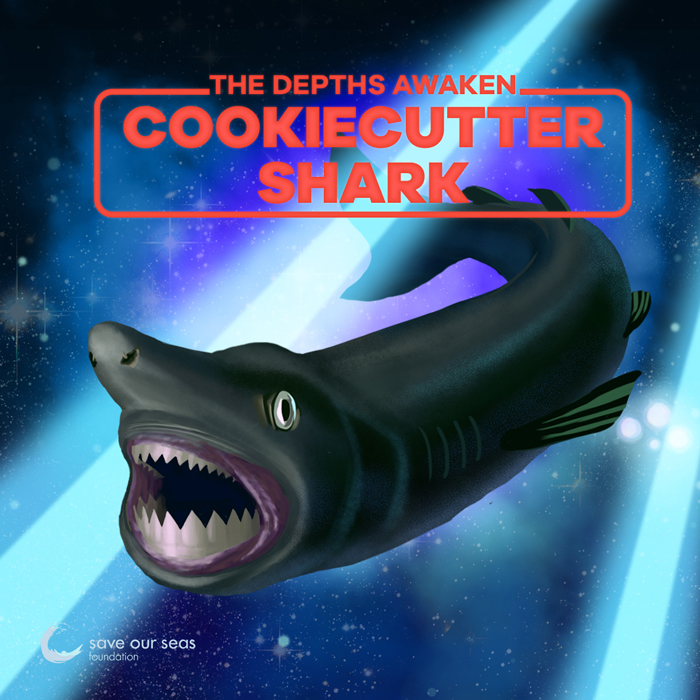

Cookiecutter Shark

The Sarlaac isn’t the only circle of teeth in town – and this one’s the deepest diver on our list!

Cookiecutter sharks (Isistius brasiliensis and Isistius plutodus) traverse the expanse of the water column, clocking extreme depths up to a whopping 3,500 meters (11,482 ft). Their trademark bites have been seen in a wide variety of prey species: from seals and whales to great white and goblin sharks. A knack for unfussy eating bolsters the cigar-shaped animal’s chance of finding food. And this species has the right tool for the job. Cookiecutters have the largest teeth-to-body ratio of any shark species!

Their jaws work like melon ballers. First, a pair of fleshy, suction-cup-like lips helps the animals latch onto prey. Once in place, the bottom teeth sink in, and with a twist of the body, a plug of flesh is removed. A set of hooked upper teeth secure the score as the shark swims away.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Megamouth shark

Despite its impressive bulk, the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios) eluded discovery until 1976. To this day, the species is known from just 102 specimens, and we’re only beginning to scratch the surface of their ecology. Where they spend the majority of their time, or just how many are out there remains a mystery. There are some clues, and one can be found inside that bulbous snout. These gentle giants are filter feeders who rely on 50 rows of sieve-like teeth to catch krill, jellies, and other plankton as they swim. Scientists believe megamouths follow that food to shallow water during nightly vertical migrations. As with apparitions of fallen mentors, sightings of megamouths are unpredictable, few, and fleeting. Each encounter reveals something new about these enigmatic creatures.

Artwork by Alexis Schofield | © Save Our Seas Foundation