Taking the Gap

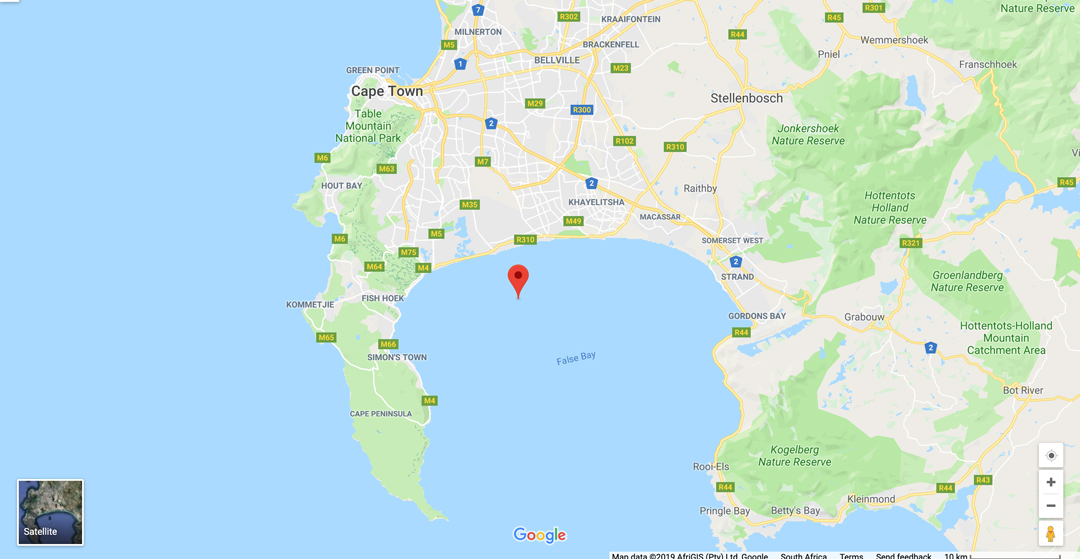

The location of Seal Island, notorious white shark hotspot. Image © Google Maps | Google

Satellite view of Seal Island. Image © Google Earth | Google

The disappearance of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) from their hot spot at Seal Island in False Bay, South Africa, coincides with increased sightings in sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus) in the same area. Typically, sevengill sharks are known from the kelp forests in the bay, but might their presence at this seal colony in the bay’s northern reaches be linked to the fall of white sharks as the region’s ruling apex predator? A new publication by Neil Hammerschlag, Lacey Williams, and Monique and Chris Fallows, investigates this possibility.

A white shark preying on Cape fur seal at Seal Island. Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

The paper, published in Nature Scientific Reports, explores a long-term dataset that has monitored white shark sightings and seal predations at Seal Island since 2000. Between 2000 and 2018, 6333 individual white sharks were tracked at the seal colony. Home to over 60 000 Cape fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus), the island is where white sharks typically concentrate their hunting activity during winter months (May – September) before moving into shallower waters inshore in the summer. While their concentrations at different locations in the bay change between seasons, some white sharks are still present at Seal Island in summer, scavenging the newborn seal pups that are washed off the island in stormy seas.

A white shark breaches for a seal-shaped decoy. Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

In 2014, something shifted … and the number of seal predation observations declined in the ensuing years. They reached an all-time low in 2018, and there were periods during 2017-2018 where white sharks weren’t sighted at all near the island. That’s including the colder months when their abundance typically peaked at the seal colony.

Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

When white sharks disappeared from the sightings records in 2017, sevengill sharks suddenly appeared for the first time in nearly two decades of monitoring at Seal Island. As white shark numbers declined from the island’s monitoring log into 2018, so the number of sevengills appearing on the monitoring radar increased. Interestingly, these two species didn’t seem to overlap in their time spent at the island: when white sharks disappeared totally, sevengills appeared, but when some white sharks returned (albeit in significantly reduced numbers), the sevengills fled the area. This, say the researchers, suggests that the arrival of sevengills at Seal Island is linked to the disappearance of white sharks from the same region. It makes sense that the two wouldn’t co-exist at Seal Island: Dave Ebert, a taxonomist who has worked extensively on sevengills, classes this species at the same level in the food chain as the white shark.

A broadnose sevengill shark at Seal Island. Photo © Alessandro De Maddalena | Shutterstock

So, why have white shark numbers decreased at Seal Island? Researchers aren’t yet sure, but some explanations include overfishing and habitat loss in the broader region that might have led to regional white shark declines. What the study does show is the value of long-term datasets, to give context to the kind of patterns we observe in the ocean today.

Photo © Tomas Kotouc | Shutterstock

You can read the paper here.

***Reference: Hammerschlag, N., Williams, L., Fallows, M. and Fallows, C., 2019. Disappearance of white sharks leads to the novel emergence of an allopatric apex predator, the sevengill shark. Scientific Reports, 9(1), p.1908.