Stories from the blue: Paul Cowley

Paul Cowley has travelled extensively throughout the Western Indian Ocean and has conducted research at numerous MPAs in the region.

Who I am

As a youngster I always knew that I wanted to study fish and become an ichthyologist. My love for fish stemmed from my passion for fishing and trying to understand more about the mysterious underwater lives of these biologically diverse creatures. Not knowing what fish were doing when I couldn’t catch them led me to take a particular interest in studying their behaviour and movement ecology.

As an undergraduate I never missed an opportunity to participate in research field trips and help postgraduate students with their projects. I always looked for vacation jobs that would keep me close to nature and, of course, the creatures that fascinate me. As a postgraduate student at Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, I made sure that my research projects involved lots of field work. During my MSc student days I joined the crews of research vessels on offshore cruises, and searching for samples I travelled widely around the South African coastline, often sleeping in my beach buggy. For my PhD I tackled a challenging project that found me sampling, counting and measuring fish for at least three days a week for three years.

My philosophy has always been to ‘follow my heart’ and today I consider myself to be an extremely fortunate person who has turned a passion for fishing and love for fish into a career.

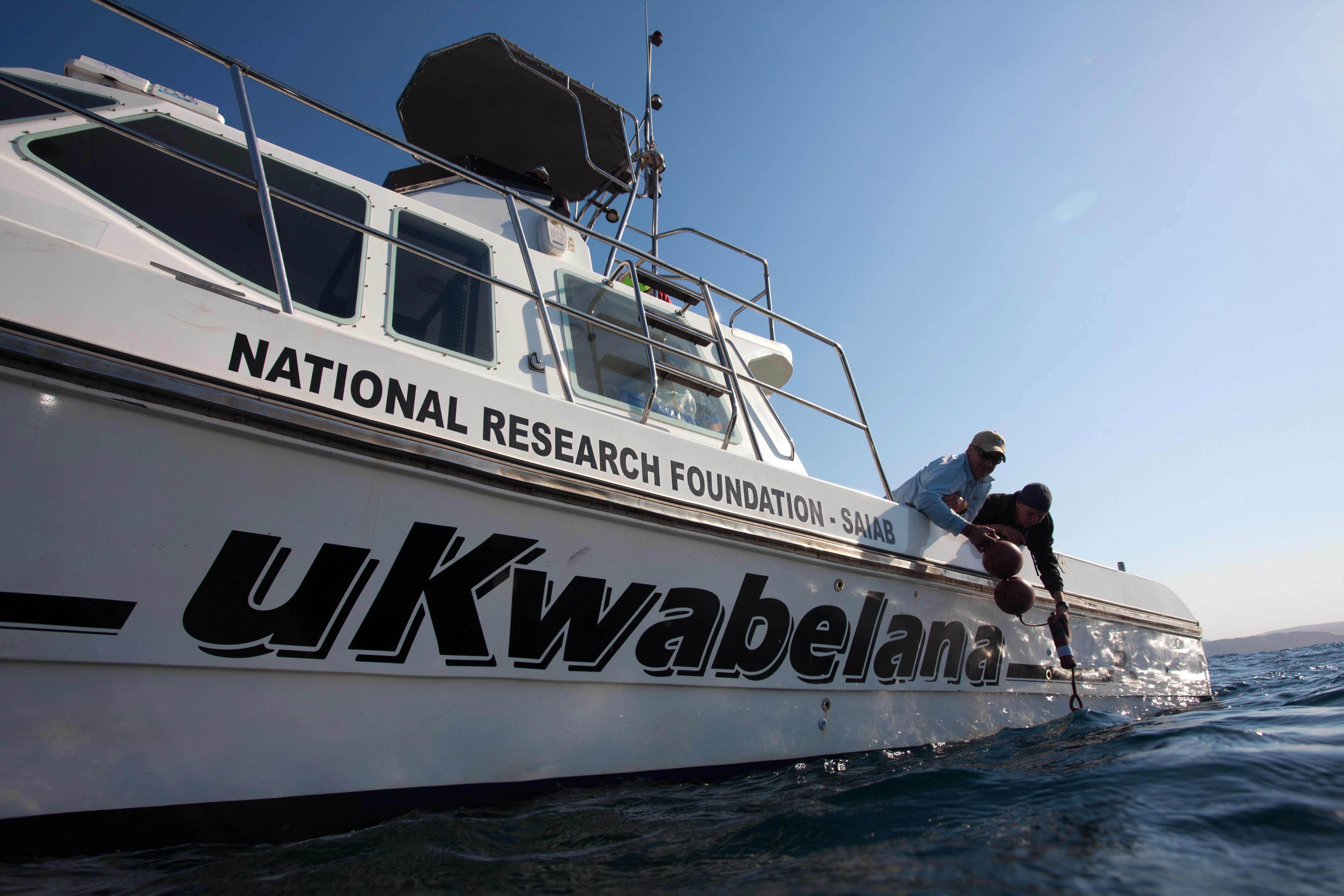

SAIAB research vessel deploying ATAP equipment in Algoa Bay. Photo by Ryan Daly

Where I work

In 2000 I accepted a position at the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), based in Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape, where I now hold the post of principal scientist. During my career I have been involved in the publication of more than 100 scientific papers and presented my research findings at conferences around the globe. Student training also forms an important part of my vocation and over the years I have been involved with the supervision of no fewer than 25 postgraduate students. I find nothing more rewarding than training and nurturing the next generation of fish biologists, not only through transferring skills and participating in field work, but also by sharing my passion for research and striving for new knowledge.

Much of my research is done in collaboration with other local and international scientists. Our studies deal primarily with the movement behaviour of fish, their patterns of habitat use and the ecology of fishery resources, with the aim of providing information for the management of these resources.

My research activities have taken me around the world and during my travels I have seen amazing things, met fascinating people and found myself catching and tagging fish at remote tropical atolls in the Indian Ocean and fishing for Atlantic salmon in northern Norway. I am also privileged to have worked in most of South Africa’s Marine Protected Areas. I am living my childhood dream!

Tagging a bull shark. Photo by Barry Skinstad

What I do

The Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP) is a collaborative research programme that provides a service to the greater marine science community in order to monitor the movements and migrations of inshore marine animals. The platform comprises a network of moored data-logging acoustic receivers around the South African coastline, from Hout Bay in the south-western Cape to the Mozambique border. Much of the acoustic telemetry hardware was provided by the Canadian-based global Ocean Tracking Network project and capital equipment grants from the National Research Foundation.

The data uploaded from the receiver network are stored on a national database and distributed on request by the scientists concerned (the data owners). Currently much of the research focuses on large predatory sharks and important coastal fishery species. There are several dedicated research projects that benefit significantly from ATAP. For example, the OCEARCH South African Shark Project has surgically equipped a number of sharks, including 39 white sharks, with acoustic transmitters that have a battery life of 10 years. Additionally, multi-institutional collaborative projects on bull sharks and estuarine fishery species will benefit from this marine science platform.

It is envisaged that this project will witness substantial growth in biotelemetry research locally. It should also foster broader national and international collaboration to ensure a sustained future for the study of migration biology and the behavioural ecology of marine animals in coastal waters around Africa.

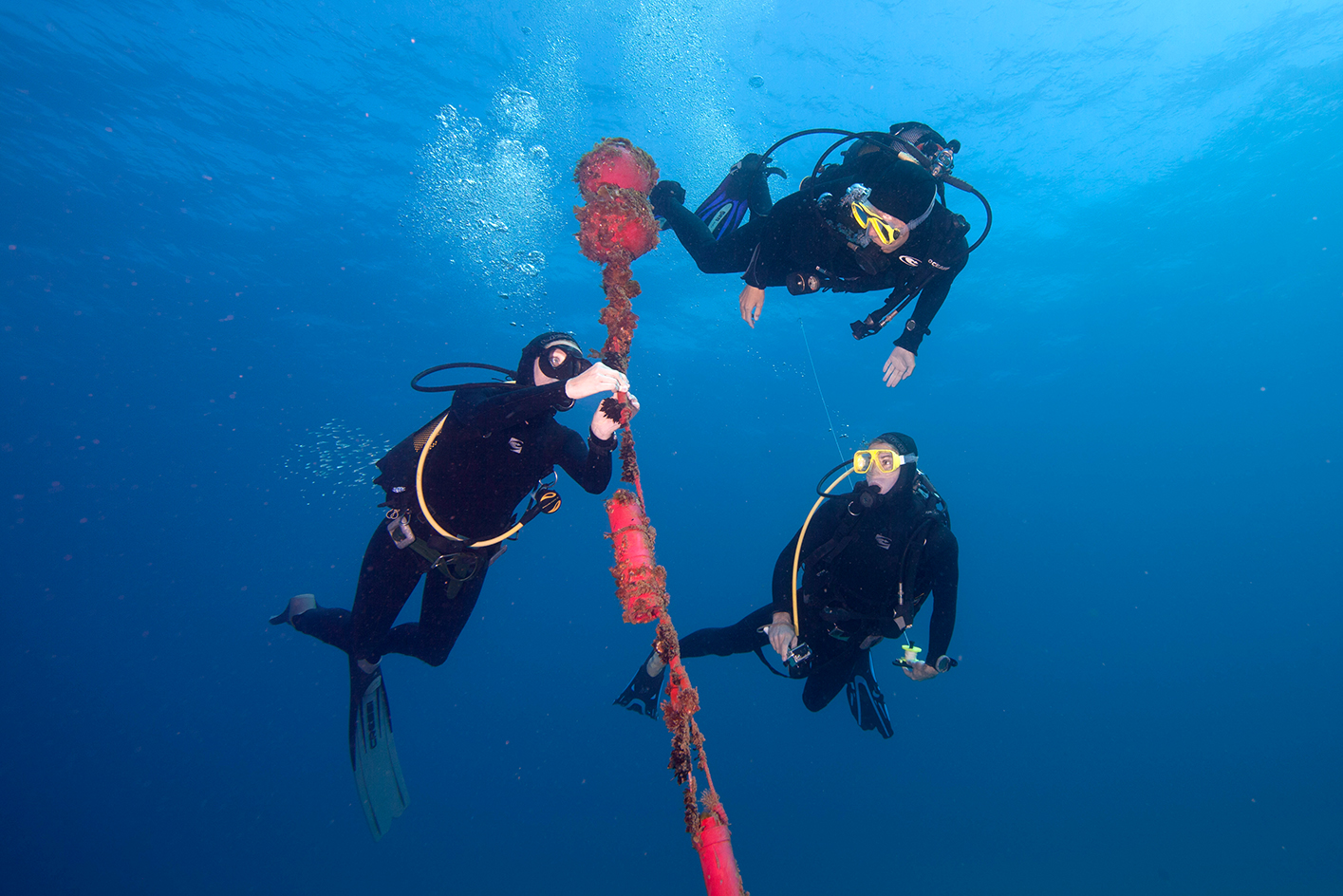

Checking a receiver. Photo by Ryan Daly

Funding from the Save Our Seas Foundation enables SAIAB to prepare, service and maintain ATAP’s national network of receivers and thus extend the geographic coverage of the animals tagged by various research teams. The impact of this will be to improve our understanding of key issues, notably the spatial ecology of several iconic conservation species; the environmental and biological factors that trigger the movements and migrations of marine animals; South Africa and Mozambique’s shared fishery stocks, and the movements of whale sharks and manta rays (both tourism species) between the two neighbours; shark–human interactions and ways to improve bather safety; and the effects of climate change, such as a rise in sea temperature.

The commonly heard phrase "money makes the world go round" is also relevant to conducting scientific research. The planning, execution and collection of research data comes at a cost and although the ATAP is a sibling of a global mega-science project (the OTN) it remains dependent on external funding from organisations like the SOSF to service and maintain a nationwide research platform. The funding provided by SOSF not only ensures that ATAP can fulfill its objectives but also allows for the collection and dissemination of data collected on animals tagged by many other researchers. Consequently, this funding plays an important role in the study of behavioural ecology and migration of marine animals around the South African coastline.