Sharks and rays threatened by climate change in the Eastern Tropical Pacific

In the Eastern Tropical Pacific, a 21 million-square-kilometre (8.1 million-square-mile) ocean region that stretches from Mexico to Peru, Pacific eagle rays and bull sharks can be found cruising the same broad blue reaches as prickly sharks and blue sharks, spine-tailed mobulas and giant manta rays. From space, satellites send images of this dynamic area that beam coded chlorophyll colours on a computer screen; the ocean here blinks reds, yellows and greens where upwelling zones abound. Upwelling off the Baja California peninsula alone is responsible for one quarter of global new primary production.

The oceanography of the Eastern Tropical Pacific is complex and active. It’s a region with frontal zones, boundary currents (like the Californian and Humboldt eastern boundary currents) and a shallow thermocline (where the temperature of the ocean changes suddenly at a depth of 25 metres, or 82 feet). It has high concentrations of surface chlorophyll, where miniscule phytoplankton (plant or microalgae) diatoms can photosynthesise in the presence of light; and low concentrations of oxygen below the thermocline. And it feels strongly the influence of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) that causes upheaval in ocean temperatures every five to 10 years.

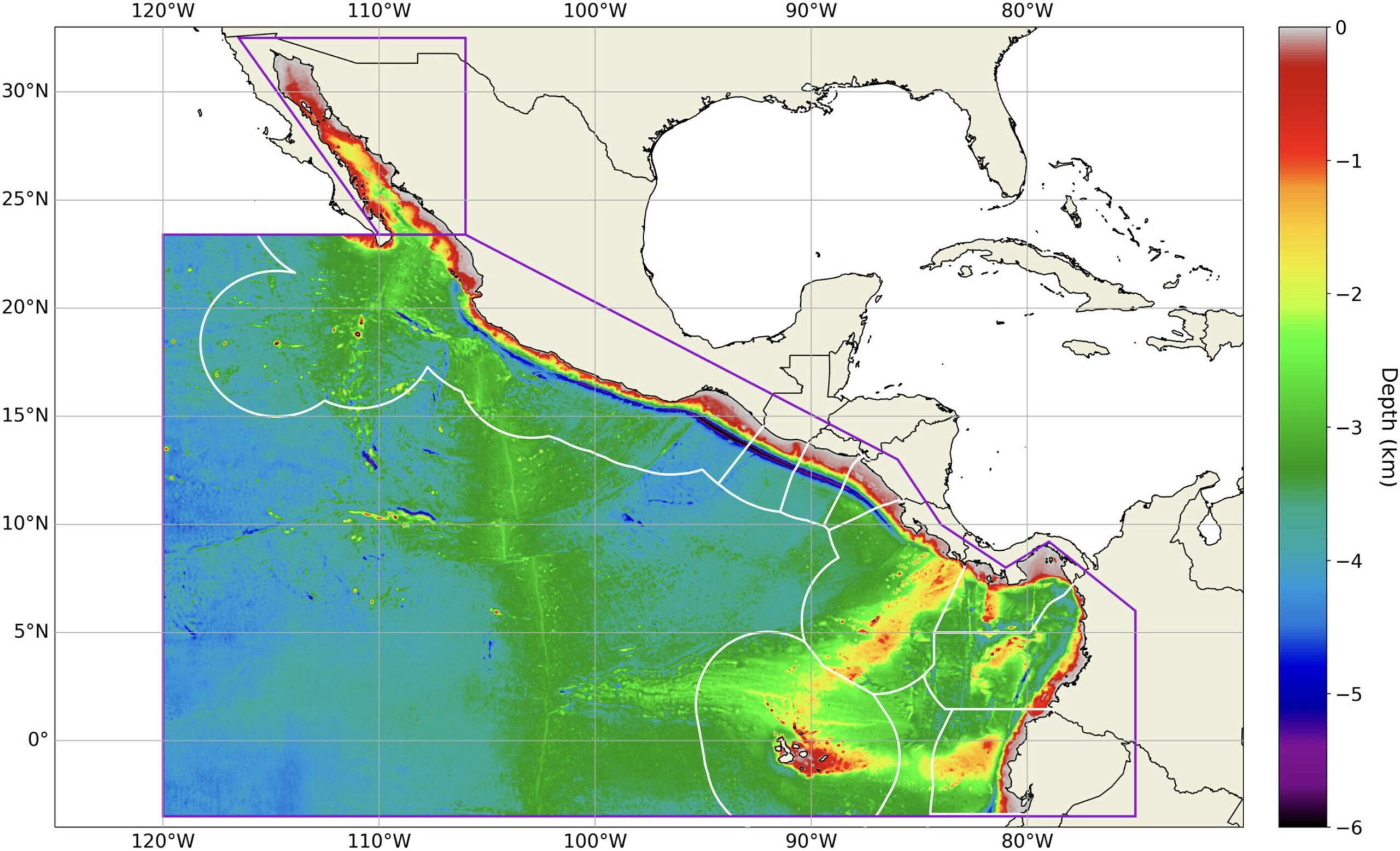

Eastern Tropical Pacific study region (outlined in purple and not depicting accepted national boundaries) including oceanic islands, bathymetry, and countries' Exclusive Economic Zone boundaries (white line).

Wild and dynamic, and characterised by oceanic islands, sea mounts, sandy flats, coastal bays, estuaries and mangrove forests, the Eastern Tropical Pacific is an important area on our planet. The sheer variety of habitat types here – and how they interact with oceanic processes – attracts a dizzying array of species, making it a site of high endemism (full of species that are found only in this region and nowhere else on the planet) and an extraordinary wealth of biodiversity.

The upwelling zones across this region also mean that biomass (the sheer number of fish) is high and fisheries here support more than 600,000 jobs and contribute to about 10% of the global fisheries catch, to a value of US$2.7-billion annually for the 10 most commercially fished species. Sharks and rays form a major part of these fisheries, with chondrichthyans – sharks, batoids (rays and skates) and chimaeras – a major component of both the target and non-target catch in industrial and artisanal fisheries in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Sharks and rays are also an important part of generating tourism income in the region.

The nature of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, with its upwelling and complex oceanography, means that it is a region likely to experience significant changes as our climate continues to change. Sharks and rays, a quarter of which are threatened with extinction largely as a result of overfishing, may be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Scientist Florencia Cerutti-Pereyra from the Charles Darwin Foundation in Galápagos co-wrote a paper assessing ‘Vulnerability of Eastern Tropical Pacific chondrichthyan fish to climate change’, which was published in the journal Global Change Biology. She and her co-authors used an integrated risk assessment to analyse the vulnerability of 132 chondrichthyans to ocean warming, deoxygenation and sea level rise, as well as changes in primary productivity (i.e. upwelling) and in salinity and freshwater inputs.

A white shark in the deep blue. Photo © Matthew During | Save Our Seas Foundation

An integrated risk assessment

A panel of 19 experts was enlisted to assess the vulnerability of the Eastern Tropical Pacific’s chondrichthyans. These scientists, who appear as co-authors on the paper, hail from eight different countries and contributed specific expertise on the habitats and ecosystems used by sharks as well as on the animals’ physiology, biology and ecology. They also brought to the table insights on risk assessment, climate change and oceanography. In a series of virtual workshops during 2020 and 2021, they hashed out a better understanding of how climate change might affect the Eastern Tropical Pacific region and what the consequences of those changes will be for chondrichthyans. The result was a risk assessment, as well as a framework to recommend priorities for research and management.

What are the potential climate change impacts?

As the heat in the earth’s atmosphere has been rising, the oceans have absorbed about 90% of this increase in temperature. They also soak up carbon and up to now have absorbed 20–30% of global carbon emissions. So even as our oceans are working as a powerful climate mediator, their chemistry is rapidly changing. And the results we’ve seen so far are warming oceans, changes in pH and oxygen levels, shifts in the availability of nutrients and a startling increase in the severity of extreme events such as storm surges.

Florencia and the expert panel identified seven key changes for the Eastern Tropical Pacific that are also likely to have a bearing on the resilience and survival of chondrichthyans: ocean warming, deoxygenation, acidification, sea level rise and changes in primary production, salinity and freshwater input. The scientists discussed how these factors would alter food webs and impact how chondrichthyans use different habitats and change their ecological interactions and physiology. Of these different factors, the influx of fresh water, changes in salinity and rising sea levels will only really impact coastal ecosystems.

How many – and which – sharks are threatened by climate change?

From the roughskin bull rays that frequent the coastal sandy sea floor in Panama and the Galápagos to Critically Endangered icons like the largetooth sawfish and great hammerhead shark and Data Deficient mysteries like swell sharks, the Ecuador skate and fake round ray, the scientists gathered information to profile 65 different sharks, 60 batoids and seven chimaeras.

Of the species they considered, 9% are Critically Endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. A further 11% are Endangered, 27% are Vulnerable, 14% are Near Threatened, 32% are Least Concern and 7% are Data Deficient.

Almost a quarter of chondrichthyans in the Eastern Tropical Pacific are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. And the risk assessment showed that most of the other species are at least moderately vulnerable. It’s a sobering result, more particularly because 77% of the highly vulnerable group are batoid species, which have a history of being overlooked, under-researched or inadequately managed. Also of concern is the fact that 90% of the species assessed as highly vulnerable either are coastal or are pelagic species that use coastal habitats as nurseries. Coastal habitats are among those that are hit hardest, as they are easier to access for a wide range of fisheries and recreational activities and are affected by land-based pollution, such as industrial and agricultural run-off that flows into the ocean via rivers. Faced with a plethora of stressors, coastal shark populations tend to be under enormous pressure already, with little resilience left to adapt to what a changing ocean might mean.

A great hammerhead swimming above. Photo © Matthew During | Save Our Seas Foundation

Species that need special attention: the endangered and the understudied

Batoids – the flattened rays and skates that are close cousins of their better-known (and often better studied, managed and protected) shark counterparts – show the highest vulnerability to climate change impacts in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. This is problematic for several reasons. There are still big gaps in our knowledge of this group, which means we often lack the nuanced information necessary to manage and protect their populations effectively.

Some of the batoids are highly specialised and rely on very specific habitats; in fact, six species are both coastal and considered rare in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. This not only makes them some of the most exposed species in terms of threats and pressures, but also the least likely to be able to adapt or cope in the face of change.

The plight of sawfish, manta rays, wedgefish and guitarfish has been recognised in international treaties like the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but the vast majority still form an important (and growing) part of fisheries and remain unprotected and unmanaged.

Species that need special attention: the nomads, movers and shakers

The shovel-shaped hammerheads, starry-skinned whale sharks and swoop-winged devil rays are iconic species of the Eastern Tropical Pacific and often a drawcard for tourism in the region. Many of these species are also migratory, showing scant regard for our political borders and relying on a variety of habitats in multiple locations. This not only complicates how these species are managed, but also introduces them to multiple stressors in different parts of their range. So adapting any protective measures becomes a tricky business, as climate change introduces shifts and switches under different jurisdictions and in different countries, which will need to cooperate if we’re to get this right.

Which impacts are the most pressing and for which ecological groups?

In the coastal, shelf and abyssal regions of the ocean, different sharks use a multitude of niches. The scientists grouped the 132 species according to their ecology (what kind of sharks are they, where do they live and how do they use the ocean?) to assess how they might be impacted by climate-related changes in different areas of the ocean. The coasts undoubtedly have it toughest; not only are most of the highly threatened species coastal, but the highest number of different impacts apply to the coast too. The kinds of habitats that are typical of the coast in the Eastern Tropical Pacific are also likely to be highly impacted. Mangroves, although a supercharged climate change ally that store astonishing amounts of carbon and protect coastal communities by mediating storm surges and erosion, are going to change with rising sea levels, increasing rainfall and worsening tropical storms. The rivers that course to the sea through Panama and Colombia will also change as rainfall patterns shift (these two countries have some of the highest rainfall records in the world), with major consequences for lagoons, estuaries and coastal habitats.

It’s a conundrum of compounding impacts: the coast represents a worrying mix of vulnerable species, threatened habitats, high rates of human activity (and, in many cases, reliance on ocean resources) and the greatest number of possible climate-related effects. The recommendation is therefore that research and management focus on the species and areas that are under pressure from multiple stressors. And immediate action is needed.

In the coastal reaches of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, a climate-smart response would be to protect mangroves, estuaries, catchments and intertidal areas. We can even pinpoint certain threats that must remain under scrutiny and design protection strategies that minimise specifically their impacts. Coastal urbanisation, changes in waterflow, eutrophication (the addition of nutrients into ocean systems via rivers and run-off from sources like agriculture and industry) and pollution are all hazards that need to remain firmly on the radar and be addressed. When the pressure on species and their habitats is alleviated from the many different stressors (including overfishing), we create a little breathing space, letting the natural capacity for resilience in the face of change recover just enough, we hope, to cope with climate impacts.

Is there any hope to hold onto?

This risk assessment re-emphasises perhaps the adage ‘where there’s a will, there’s a way’. The act of gathering experts, pooling their insights and brightening the spotlight on where we will need to focus is a decisive and determined confirmation of the commitment many conservationists and scientists still show in the face of really worrying trends.

Florencia and her co-authors emphasise that the information they present can be used to inform fisheries management and spatial protection plans as well as identify species-specific research and management priorities. There are still large gaps in knowledge, but no effective action can be taken until these are identified.

The assessment gives us the sense of urgency that underscores climate change action and adaptation. Real change will require international commitment and cooperation in the Eastern Tropical Pacific’s vast and complex reaches. There is, it is clear, no time left to waste – and when we pay heed to critical, strategic work like this, we have a real chance to turn the tide for sharks, rays and their cousins.

**Reference: Cerutti-Pereyra F, Drenkard EJ, Espinoza M, Finucci B, Galván-Magaña F, Hacohen-Domené A, Hearn A, Hoyos-Padilla ME, Ketchum JT, Mejía-Falla PA and Moya-Serrano AV. 2024. Vulnerability of Eastern Tropical Pacific chondrichthyan fish to climate change. Global Change Biology 30(7): p.e17373. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17373.