Shark Share Global is here

Lauren Meyer and Madeline Green are the founders of Shark Share Global, a newly launched online platform that enables researchers to share shark and ray samples with other scientists around the globe. We asked them a few questions about their new initiative and the impact they hope it will have.

What is Shark Share Global?

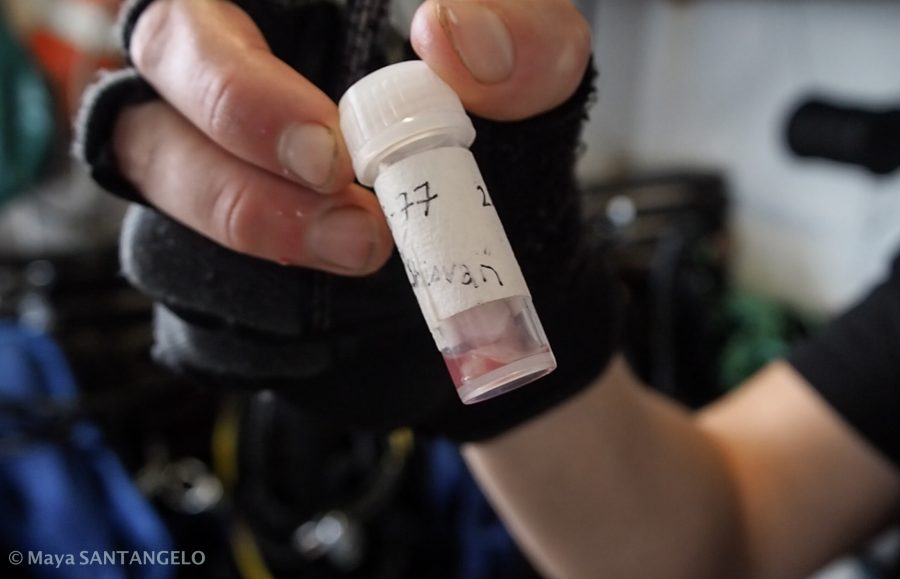

Lauren: Shark Share Global is an online database for research scientists to submit, search and request tissue samples from colleagues around the world. As scientists, we collect and save a variety of parts from the animals we study. Having a platform to see what people have already collected enables us to share these samples with other research teams, collectively discovering more about sharks, rays and chimaeras. It is basically a nerdy garage sale platform, moving samples from the back of people’s freezers into the hands of researchers who need them.

How did you get the idea for this project?

Lauren: Like many ideas, Shark Share was born out of a mishap, a chance encounter and an off-handed comment. I had just wrapped up a project looking at tropical toxins in shark livers, but had been unable to source any samples from large sharks that are likely to accumulate this particular toxin. A month later, at the Oceania Chondrichthyan Society (OCS) conference, I was chatting to a fellow scientist who mentioned that they had 20 tiger shark livers just sitting in their freezer and weren’t sure what to do with them. I couldn’t believe it – after all the phone calls and e-mails I had sent, searching for samples, the livers I’d needed were sitting in a freezer in the same state! In a bout of frustration, Madi and I went to the OCS president and demanded access to the database of all the samples that people have sitting in their freezers. Looking very confused, he informed us that no such thing exists, but we should ‘just go make it’. It sounded so simple at the time.

Why is there a need for a platform like this?

Lauren: Collecting research material is challenging and expensive; it often takes many years to source enough samples to complete a project. Knowing about these challenges, scientists save extra tissue, not only for their own projects, but for others as well. So there are stores of samples already collected and there are innumerable collaborative projects waiting to be undertaken. However, with no way of knowing who already has samples, these opportunities are often missed. In research this can mean smaller sample sizes, regional instead of global projects, and understudied species. Unfortunately, many chondrichthyans are threatened by human impacts such as overfishing and coastal development, or we lack sufficient basic biological data to assess whether a population is at risk. Better communication can reduce some of these challenges, enabling us to grow our capacity as a community and become more effective researchers.

Do you anticipate any concerns that scientists might have about sharing their samples so freely?

Madi: We certainly understand that sample sharing requires trust between researchers and collaborators and we have been asked many questions about how we deal with authorship agreements and shipping details. When samples are uploaded, an acknowledgment and shipping agreement is created. We also see that researchers may be hesitant to upload samples without knowing who is on the database. For this reason, Lauren and I check all users before approval to ensure they are researchers from registered institutions. This is a new tool and a new way of thinking about how we share samples, so we are sure there will be some reservations. However, we believe the benefits of this kind of online system and communication pave the way for how we collaborate now and into the future.

Madeleine processing samples in the lab.

A shark DNA sample is stored for genetic research.

How long does it take to upload a sample and how does the process work?

Lauren: It takes no more than 15 minutes to upload samples. Researchers simply download the Excel template and then copy and paste into it the relevant information from their own sample records. There are 21 columns in which data can be entered, but only nine are mandatory, which makes it easy to include as much or as little information as the user wants to make available. The data include things like the species, the type of sample (an eyeball or a fin clipping), how it is preserved, where it came from, and how the contributor would like to be acknowledged for the samples. Users then upload the Excel sheet straight into the database. That’s it. This process was designed so that researchers can upload large batches of samples all at once, with an Excel program they are already familiar with.

How long has it taken to build the platform?

Madi: I wish we could say it took us less than a year and it was a simple process, but that’s not the case. Trying to make a tool that is novel and intuitive, and selecting the right people with whom to work and develop the database, has easily been one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced. The idea was formed in 2013 and since then we have been working on the database. That’s right – four years!

What kind response have you received so far?

Madi: We have had such an overwhelmingly positive response from not only the shark and ray community, but also researchers from other disciplines. In our first week we approved users from nine different countries and hundreds of samples have been uploaded to the database. Each day we usually receive one or two new user requests and have a number of users currently organising their samples in preparation for upload. We are really grateful to have researchers from all over the world supporting Shark Share and we hope this tool will enable all scientists to complete more projects, create more collaborations and share more samples.

What is Otlet and what plans do you have for it?

Madi: Lauren and I often present Shark Share at conferences and are asked by non-chondrichthyan researchers if Shark Share would be available for their species of interest. While we love sharks and rays, we thought it would be unfair to create a database that is exclusive – and so we came up with Otlet.

We named it after visionary information scientist and author Paul Otlet and aim to encapsulate his ideals: universally accessible information and the building of an infrastructure to link people and enable discoveries. Otlet will provide a service similar to that of Shark Share, but for all species and all tissues. This is a huge undertaking for Lauren and me, but we know that Otlet will make incredible and far-reaching benefits available to the scientific community and will improve our understanding of species worldwide.