Searching for sharks at the ‘Navel of the World’

A little over three years ago, a determined PhD student set out to document the sharks cruising the seas around the remote island of Easter Island. For Naiti Morales Serrano, some clues that once predators ruled the clear Pacific waters around Rapa Nui (as it is known locally) lay in the ancient petroglyphs carved into the island’s rocks. Her mission was to document the ocean’s predators using modern technology that could afford her new access to an under-researched region. Naiti needed evidence of the marlin, tuna and sharks etched into the island’s archaeology, and still reported by local fishers, but whose presence her colleagues doubted. Today, her underwater camera findings will help to identify priority protection zones that can conserve the sharks in the newly declared Rapa Nui multiple uses marine protected area (MPA).

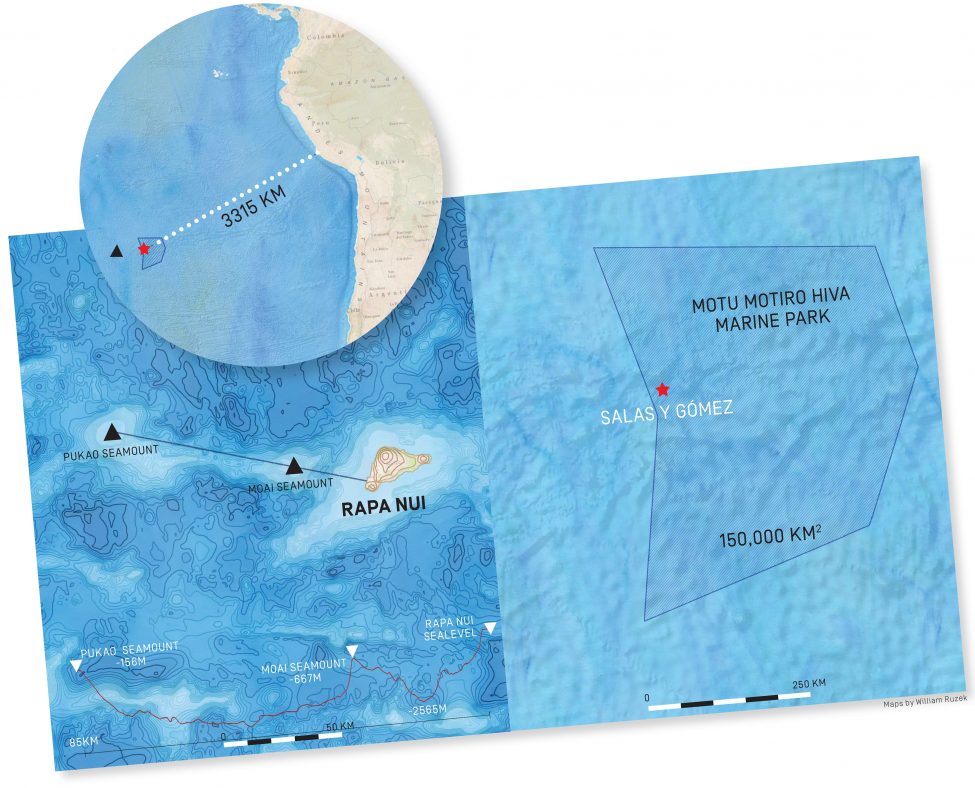

Map by William Ruzek | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Naiti published the results of her survey at Easter Island in the journal Aquatic Conservation in late 2019. Her paper, titled Spatial and seasonal differences in the top predators of Easter Island: Essential data for implementing the new Rapa Nui multiple‐uses marine protected area baited remote underwater video recorded fifteen pelagic (fish that swim in the open ocean’s water column) species. Of these, nine species were considered top predators: the large sharks and fish that reign at the top of the oceanic food chain. It was a win for Naiti: confirmation that the stories she had heard from local fishers – of the Galapagos shark and the tunas that hadn’t been detected in other researchers’ SCUBA surveys – were correct. With local names that some may recognise, like barracuda and bonito; and others like kahi and toto amo that are new to the tongues of those outside Rapa Nui, the richness of top predator species (how many different species) was high. But their abundance (how many individuals within each species) was lower than that of species further down in the food chain.

108 Yellowtail amberjack were counted during the survey. Photo © Janelle Orth | Shutterstock

Two small, planktivorous fish, dubbed Randall’s chromis and the redtail triggerfish, were the most abundant species around the island. Next in line was the Pacific chub – an innocuous little herbivorous fish. A somewhat different picture to the Rapa Nui of old, painted by the island’s petroglyphs – and a very different view from the modern-day reference point that is the uninhabited neighbouring Isla Sala y Gómez 400 km to the east. Naiti and her co-authors had placed such importance on recording the abundance and whereabouts of sharks and other top predators around Rapa Nui because they play an essential role in the ocean ecosystem. Their presence and diversity are vital to the continued functioning of the island’s ecosystem. Naiti’s survey helps to inform the continued monitoring and protection of these top predators. These are conservation imperatives necessary to ensure that the island’s ocean continues to provide sustainable resources – what ecologists call “ecosystem services” – to the people who live on the world’s most remote, inhabited island. Naiti believes that it now seems likely that the waters around Rapa Nui have shifted from a healthy ecosystem like the one at the neighbouring Sala y Gómez Island (where top predators are abundant) to a disturbed ecosystem dominated by planktivores and herbivores.

A Galapagos shark. Photo © Fiona Ayers | Shutterstock

While Naiti’s survey is heartening confirmation that sharks do indeed still exist in the oceans of Rapa Nui, her findings have critical conservation importance, given that their numbers are simply not what they might once have been. Continued declines in the sharks around the island from overfishing threaten the stability of a fragile ecosystem. The Chilean government has protected the waters around both Rapa Nui and Sala y Gómez in a multi-user MPA. For this MPA to work effectively, it needs to be zoned appropriately to accommodate the interests of the various people who rely on these ocean ecosystems, while safeguarding the most sensitive habitats and threatened species so that they can recover from overexploitation. This means that some no-take areas, where all extractive human activities such as fishing are prohibited, must be created. The information from Naiti’s survey can help policymakers identify the most critical areas to protect, like the possible Galapagos shark nursery identified to the south-east of the island. Knowing which species are around the island is only one part of helping guide this process; policymakers also need to know where these fish live, and if their abundance changes seasonally. Naiti’s survey showed that the fish community on the south coast differed from that in the east and the west and that its composition changed as bracing swells crashed onto the exposed southern coastline from Antarctica in winter. Findings like these will help guide how people and the environment can thrive at an island so wild and remote that it has been called the “Navel of the World”, where human-reliance on the ocean is very clearly a matter of survival.

Photo © Marc van Kessel | Shutterstock

Reference: Morales, N.A., Easton, E.E., Friedlander, A.M., Harvey, E.S., Garcia, R. and Gaymer, C.F., 2019. Spatial and seasonal differences in the top predators of Easter Island: Essential data for implementing the new Rapa Nui multiple‐uses marine protected area. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 29, pp.118-129.

Read the paper here.