Saving sharks at CITES COP19

There is only one place on earth where a hippopotamus would be encountered in the same room as a Chinese water dragon. And a short-tailed albatross could be found alongside a Mexican prairie dog. From 14 to 25 November 2022, Panama City will play host to the nations tasked with determining the fate of some of the planet’s most endangered and widely traded wild animals. The proposals for listing this bewildering array of biodiversity on either Appendix I or II of the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) have been lodged and form the basis the 19th meeting of the Conference of the Parties in Panama.

What is CITES?

States and economic regions can volunteer to agree to CITES, an international mechanism to regulate trade in endangered species. A species listed on CITES Appendix II requires a higher degree of monitoring and scrutiny at border posts; nations need to demonstrate that any trade in that species is sustainable and must provide a permit to do so. Trade in species listed on Appendix I is highly regulated and may be entirely prohibited.

What does CITES mean for sharks and rays?

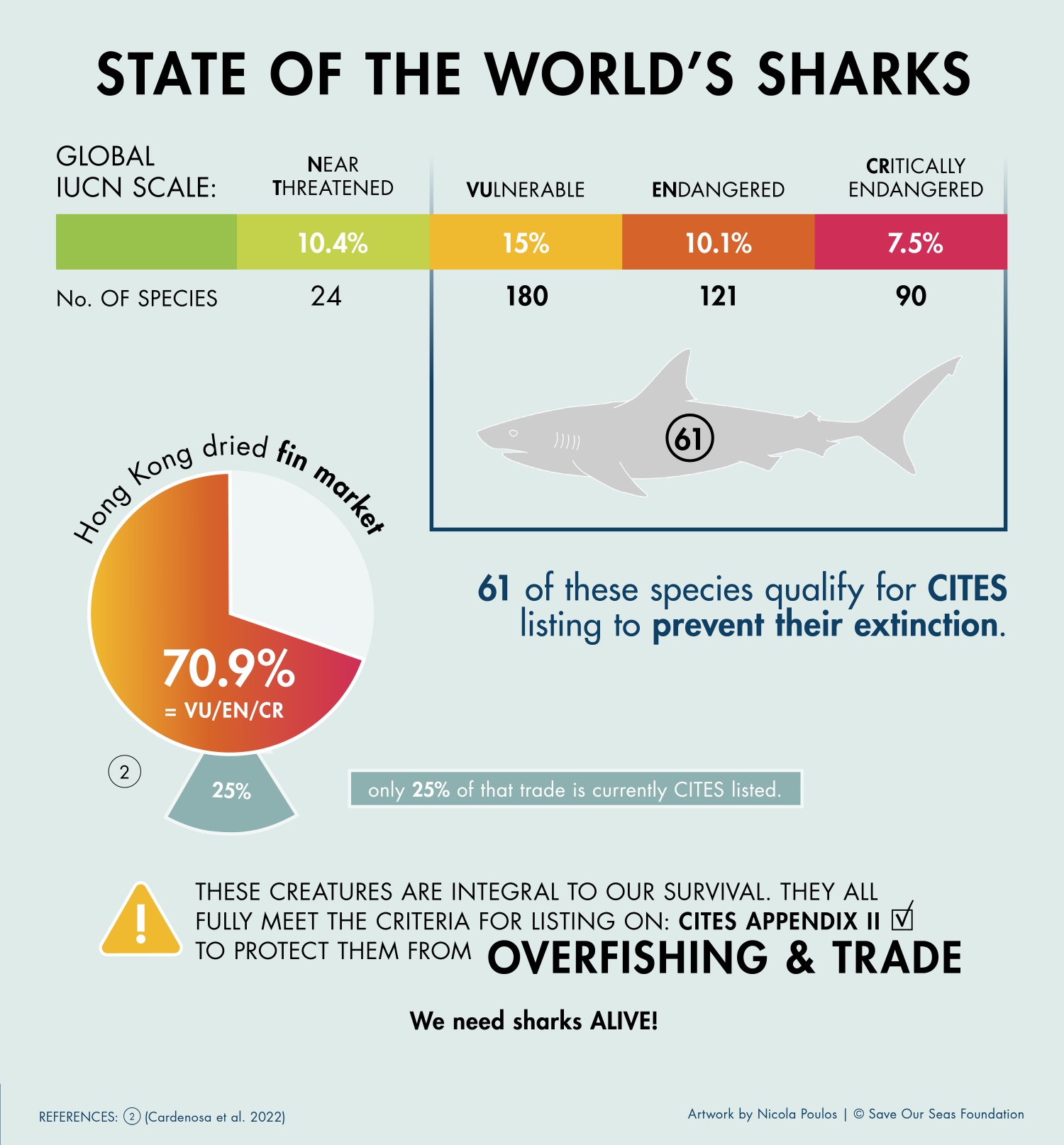

An astounding 70% of shark species found in the Hong Kong fin market (the world’s largest) are listed in the Critically Endangered, Endangered or Threatened categories on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List. However, only 25% of those species being traded are currently listed on CITES. These numbers are so high that you can expect every shipment of fins that arrives at a border post somewhere in the world to contain threatened species.

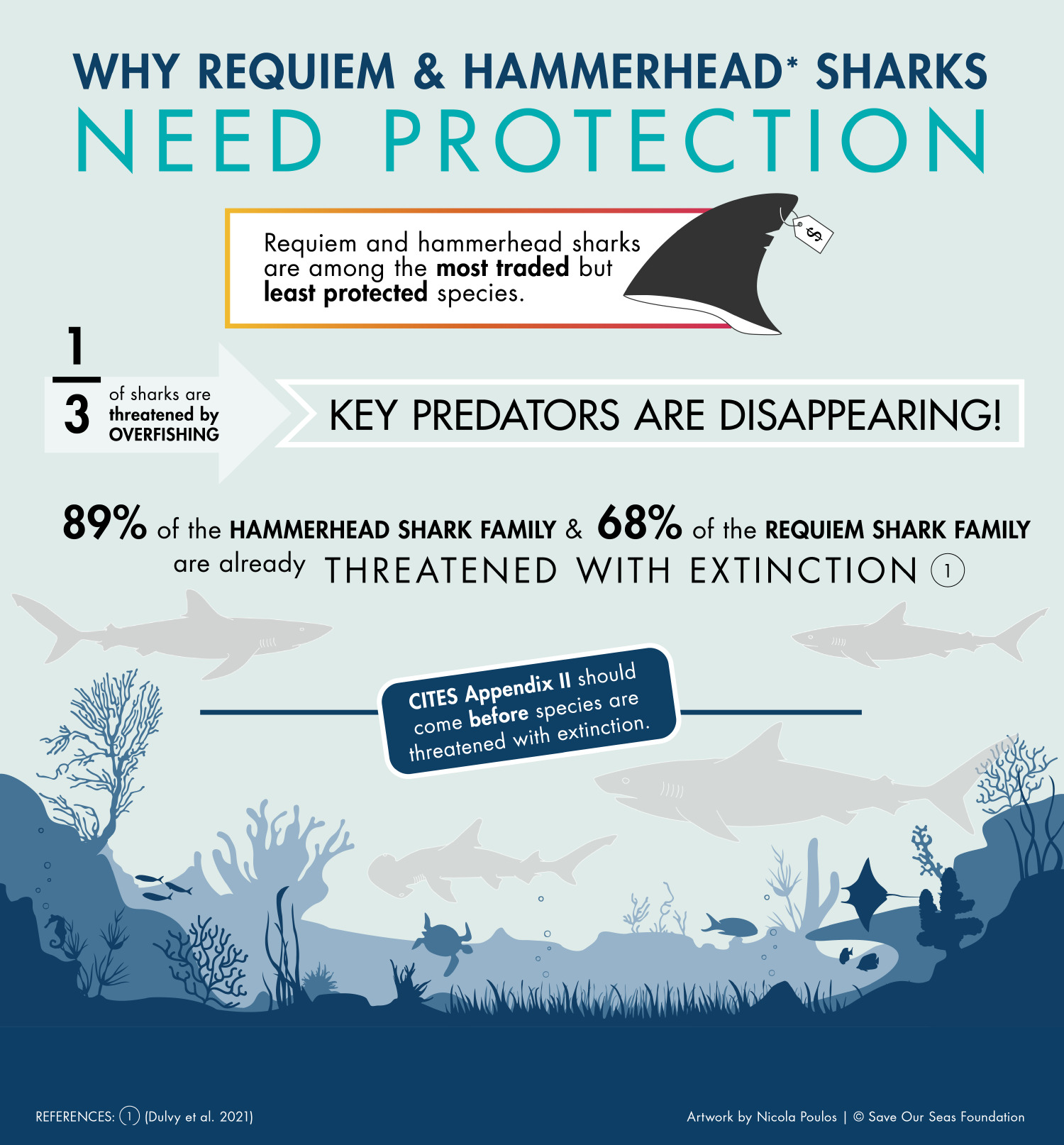

It’s also a mere seven families of sharks and rays that make up more than 90% of the global fin trade and account for 100% of the trade in dried ray gills. With five of those families already listed at the family level on CITES Appendix II, the major global gap is the requiem shark and small hammerhead shark families. This year, 19 species of requiem sharks and the bonnethead shark (a species of small hammerhead shark) are proposed for listing on CITES Appendix II. All remaining species in both shark families will be listed as look-alike species. It’s a move that, if approved, will bring 90% of the international fin trade under regulation and address the mixing of listed and non-listed species’ products in trade.

7 families of sharks and rays make up more than 90% of the global fin trade, and account for 100% of the trade in dried ray gills. The major global gap is the requiem shark and small hammerhead shark families. Photo © James Loudon

Why is it important to regulate trade in requiem and small hammerhead sharks?

Requiem sharks make up the largest shark family in the world. At least 56 different species are described in this family, the Carcharhinidae. Requiem sharks are found around the oceans: in tropical waters, on coastal continental shelves and in waters offshore. They are found in the subtropics and in temperate seas, and some, like the Ganges shark, even live in freshwater rivers and lakes. Divers will know these sharks well, as requiem sharks make up the most diverse and abundant group of sharks on coral reefs globally. Of all the species in the requiem shark family, 68% are threatened with extinction. And yet requiem sharks are among the most traded species in the world. Nineteen species have been proposed for listing on CITES Appendix II because they are all classified as Critically Endangered or Endangered.

The bonnethead shark can be found finning through shallow coastal habitats such as sea-grass meadows, mangroves, estuaries and reefs. While the Endangered bonnethead is the lead species proposed for Appendix II, the five other small-bodied hammerhead species will be listed as look-alikes because their fins and products are indistinguishable in global trade.

Coral reefs and sea-grass meadows are important homes to most requiem sharks and the bonnethead shark. They are also habitats that provide humans with vital services. Coral reefs give us food and jobs and help to buffer the worst effects of violent coastal storms, saving lives and reducing the cost of adapting to climate change. Sea grasses help us combat climate change by absorbing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. We need to maintain requiem and hammerhead shark populations in these habitats because they regulate prey species, cycle nutrients and maintain the food web, keeping these superpowered ecosystems healthy and functioning.

Twenty per cent of coral reefs around the world have lost the important functions provided by their shark populations. That’s the conclusion from a survey that explored shark populations on the coral reefs of 58 countries. Many shark species have disappeared entirely from the reefs where they used to live. In other places, their numbers are now so low that they can no longer provide the services vital to keeping coral ecosystems functioning. Listing requiem and small hammerhead sharks on CITES Appendix II this year is a precautionary measure – a wise move that means protecting sharks before their numbers drop so low that many would have to be entirely banned from capture.

Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Artwork by Nicola Poulos | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Which other sharks and rays are proposed for listing at CITES COP 19?

Freshwater stingrays and marine guitarfishes are also proposed for listing on CITES Appendix II at CoP19. The other shark-like ray families, the wedgefishes and giant guitarfishes, were listed in 2018 (and sawfishes had been listed previously on Appendix I). Six Critically Endangered species of guitarfish are proposed this year. The remainder of the guitarfish family, the Rhinobatidae, are proposed for listing on Appendix II as look-alike species. Should this motion pass, trade in the highly threatened and intensely traded shark-like rays would be much more coherently and comprehensively managed.

Caribbean reef sharks are classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on their Red List as Endangered. Photo by Shin Arunrugstichai | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Three quick ways you can get involved in CITES COP19

- Drum up the support! Voting to add the requiem sharks, small hammerhead sharks and guitarfishes takes place on 17 November 2022. Follow the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and the Humane Society on social media to keep track and voice your support online.

- Read and share! Learn about CITES listings past and present and the proposed listings on the CITES Sharks and Rays website and on our website.

- Use your vote. This CITES conference is symbolic of a bigger issue: we need to address the biodiversity crisis. Push for your political leaders (who will end up voting on key wildlife issues on your behalf) to be savvy about conservation issues and to put sustainability – your future on this planet – first.