Ripple effect

Impacts of Covid-19 on coastal communities and conservation

As Covid-19 swept around the world, humans’ lives changed significantly, as did the lives of many other species. But was the pandemic good news for the oceans’ inhabitants or is the real story more complex?

In need of good news as many of us struggled to adapt to a vastly different reality of restricted movements and working from home during the height of the pandemic, we may have been buoyed by stories of wildlife taking to empty streets in cities around the world. In Japan, sika deer wandered through streets and subway stations. Mountain goats roamed a town in Wales, while in Argentina sea lions appeared on the traffic-free roads of a seaside port.

But Covid-19 was not all good news for wildlife and many conservation efforts in low-income countries have been hard hit. Estimates of its impacts suggest a 75–90% decrease in international tourism in 2020. This has put as many as 120 million jobs at risk around the world. For people living in low-income countries where furlough payments or unemployment benefits do not exist, the loss of work threatens their very survival. As lockdowns resulted in the disappearance of previously reliable forms of casual employment, like driving a taxi or serving in a shop, a large number of people may have turned to the natural world as the only source of food or income. In addition, many conservation groups, especially those in poorer countries, depend heavily on the money and involvement of volunteers to keep their programmes running. Pandemic-related travel bans resulted in the drying up of this source of income and labour.

The effects of the global pandemic on our oceans and their inhabitants have clearly been diverse. Here we examine some of the reports of the many impacts, positive and negative, that the virus – and especially the halt to marine tourism – has had on sea life and marine conservation efforts.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Mozambique

The Bazaruto Archipelago, a group of five white-sand islands surrounded by sparkling turquoise waters, is a popular high-end tourism destination in southern Mozambique. The tiny village of Mangalisse lies just south of the archipelago, on the mainland. Until two years ago, fishing was the only real livelihood there for most of the community. The shallow sand banks are exposed at low tide, enabling women to walk far out to sea-grass beds where they collect oysters, while men take their wooden dhows (sail boats) out to deeper waters to catch whatever they can: fish, crabs and, sometimes, what the locals call ‘diamonds’, or seahorses.

Not long ago, every one of the 120 or so families in Mangalisse was poaching these tiny animals, which are protected by law, and selling them for considerable sums to visiting buyers. Dried seahorses are exported to Asia, where they are used in Chinese traditional medicine to treat conditions such as asthma and arthritis. For most families in Mangalisse this was the primary source of income and far more lucrative than selling seafood. In 2018 the local environmental NGO ParCo launched an educational campaign about seahorse conservation in Mangalisse. It also worked with the community to develop a seahorse snorkelling safari business: local fishers took visitors out by dhow to see seahorses in their natural habitat. The community came to appreciate that seahorses could be valuable alive as well as dead. Ruben Afonso, a fisherman from the village and former poacher, noted that after the seahorse tours took off, each family could count on an occasional financial boost from a safari and didn’t have to worry so much about getting all their income from their fish catch.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

But when Mozambique closed its borders in March 2020 and tourism disappeared, the entire community of Mangalisse was left without this source of income. Whether this encouraged the resumption of seahorse poaching is unknown, as anyone who may be involved is now more secretive about their activities than in the past. Certainly, without tourism many members of this community face difficult decisions, in which their basic needs may appear to be in conflict with the goals of seahorse conservation.

Illustrations by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Olinda Joaquim is a Mangalisse resident who buys fish from the local fishers and sells it in the neighbourhood. But the impact of the pandemic meant a huge change in the local market for seafood, as the nearby town of Vilankulo, usually a tourism hotspot, became empty. ‘The bars we used to sell squid to have closed,’ she said. ‘The fishermen don’t go out every day because they know they won’t be able to sell what they catch. The price has gone way down and no one is buying. I am doing about 20% of the business I used to do.’ Olinda also used to be involved in the seahorse safaris, preparing a traditional Mozambican lunch to serve to visitors after their trip. This significantly improved her earnings, enabling her to work on her home. ‘Since coronavirus, no one comes for lunches. I used to make plans to finish my house. But now there are days I don’t eat lunch because money is short,’ she added.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Namibia

The Skeleton Coast is a wild and lonely place most of the time, but Namibia is a popular niche tourist destination and many visitors take a trip to the starkly beautiful coastline. Naude Dreyer is the founder of Ocean Conservation Namibia, a non-profit organisation that aims to end the entanglement of marine wildlife along the country’s coastline. Naude is based in the town of Walvis Bay, where tourists are taken out in boats to watch the noisy and playful Cape fur seals that inhabit Pelican Point, a long sandspit at the bay’s western edge, and the bottlenose dolphins and Heaviside’s dolphins within the bay.

While Namibia was in lockdown, Naude went out to Pelican Point at least five times a week and from March onward he and his team caught and disentangled well over 500 Cape fur seals, usually from fishing line and plastic packaging. He noted that the lack of boat activity in the bay and of cars driving on Pelican Point gave them more opportunity to do their disentanglement work, which was good news for seals that would otherwise have suffered long-term and increasing discomfort and sometimes physical disfiguration.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

In his frequent trips to the sandspit, Naude began to notice other changes in the area’s wildlife. ‘About a month into the lockdown I started seeing brown hyena tracks again at Pelican Point. This is the first time in at least three years I’ve seen the tracks there,’ he commented. The brown hyena is one of the rarest of Africa’s large carnivores and populations are declining across the continent. The hyenas still live in the delta area to the south of Pelican Point, but had stopped visiting the point itself, perhaps to avoid the many cars and people who fish from the beach. ‘There are now two sets of tracks heading to and from the point every morning when I get out there,’ he said, clearly enthusiastic that these rare and shy animals were taking back their territory in the absence of humans.

Illustrations by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Meanwhile, things also changed for the bay’s aquatic residents. ‘We’ve been having the most amazing sightings of Heaviside’s dolphins from the beach, almost daily,’ Naude remarked. ‘Usually, the area where we’re seeing them is full of tour boats and we don’t often get to watch them just hanging around, doing their own thing.’ Although the lack of research in Walvis Bay during lockdown means we can’t know for sure what might have changed the behaviour of these charismatic dolphins, undoubtedly there has been a reduction in underwater noise caused by boat motors. Research has shown that noise from boat engines can cause stress and mask communication signals among dolphins, so they may have welcomed the quiet. Whatever the reason, it apparently put Walvis Bay’s most striking little inhabitants in a good mood.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Caribbean

Ocean Spirits is a conservation NGO working on the island of Grenada that protects the nesting and foraging sites of leatherback and hawksbill sea turtles. The Grenada government decided early in the pandemic to close its airports and enact strict regulations restricting people’s movements, which were effective in controlling the spread of the virus. Unfortunately, the measures had unforeseen impacts on turtle conservation. ‘The absence of international volunteers meant a loss of funding and a lack of personnel to patrol the beaches where turtles nest,’ noted Kate Charles, the project manager for Ocean Spirits. Initially, they had to stop their beach patrols completely, which put the turtle nests at risk from those who dig up the eggs to sell for local consumption.

‘Eventually, we were allowed to resume our beach patrols, but were restricted to only two hours per night when we are accustomed to patrolling for 10 hours,’ Kate continued. This left turtle nests vulnerable to exploitation for long periods during the hours of darkness. Ocean Spirits teams have documented that at least 20% of turtle eggs have been collected this year, which is concerning given that they usually record levels of about 3%.

In response to the pandemic, some funders withdrew their support for conservation projects, which resulted in Ocean Spirits losing its funding to monitor the small offshore island where hawksbill turtles nest. Without the resources to travel to the remote site, they were unable to maintain a presence there and now know that turtle eggs were harvested and turtles were killed for their meat. The presence of local NGOs at remote sites can be critical for the protection of the lives of endangered animals.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Didiher Chacon, executive director of Latin American Sea Turtles, and his team had similar experiences in their efforts to protect turtle nests in Costa Rica. ‘Many communities are facing loss of employment and income, especially in the most rural areas, and we have seen an increase in egg poaching as people struggle to sustain their families. Eggs are being taken not only for consumption, but also for sale on the black market. Many people who have lost their jobs due to the pandemic are returning to this practice to make ends meet,’ he explained.

Illustrations by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

But on a more uplifting note, he noted that the pandemic has also revealed a sense of stewardship for turtles that has developed in communities, even when times are hard. ‘The people of Pacuare, despite not receiving a salary from the project, have continued to support and assist our staff with night patrols and nest monitoring. This indeed is a testament to their commitment to the environment and the protection of the nesting turtles that visit their beach.’

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Madagascar

Blue Ventures, an NGO working to rebuild small-scale fisheries in coastal communities throughout the tropics, has been documenting the variety of impacts that the pandemic has had on the people its teams work with. As fish populations have declined in recent decades, many coastal communities have attempted to diversify their livelihoods and become less reliant on fishing. Some turned to tourism, providing home-stay accommodation and developing small businesses that supply services to tourists. But with the collapse of tourism worldwide, these small business owners may have lost their sole source of income, or at least a significant one. Blue Ventures documented that as the pandemic caused job losses in the tourism industry, many people in Tanzania turned to fishing to earn a living. Indeed, this is likely to have occurred in many coastal communities that were once reliant on tourism, but in areas where fish populations are already depleted, such additional fishing pressure could now undo local efforts to manage fisheries sustainably.

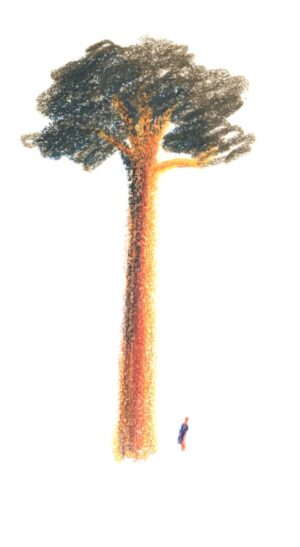

The collapse of tourism also had a significant impact on Blue Ventures’ work in Madagascar. Until 2020, the NGO ran a marine ecotourism programme in the village of Andavadoaka. Expedition volunteers stayed in the village and were trained in coral reef monitoring. They then spent several weeks diving the region’s reefs and collecting valuable information on the corals and other marine life at both protected (no fishing allowed) and fished sites. These data provided valuable insight into the effects of the management decisions communities were taking. For example, more fish, bigger fish or healthier corals in areas closed to fishing suggests that no-take zones may bring about more healthy marine ecosystems and eventually better fish catches.

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

As data accrue over years, communities can learn which management activities are helping them to reach their goals of healthy fish populations and resilient marine ecosystems and they can make informed decisions about their future. The forced closure this year of the volunteer programme could have meant no data on coral reefs in 2020, or perhaps even an end to monitoring. Instead, the Blue Ventures team turned the challenge into an opportunity: they launched a new programme to train local community members to collect the much-needed data.

Having a local monitoring team has reduced reliance on visiting volunteers to provide the data for management decision-making. This in turn ensures the long-term resilience of the community to any potential future changes in the tourism market, such as that caused by Covid-19. It has also reduced the gap between data collection activities and the sharing of those data with the community, because data are collected, processed and explained to the community by the same local team, in the Vezo language and using terms that everyone understands.

‘For people living in Andavadoaka, life is not easy. Many families rely on fishing as their main livelihood, but income from fishing is not always guaranteed. Being involved in ecological monitoring has not only meant earning a stable income, but has also given these men a voice,’ noted Javier del Campo Jimenez, the science coordinator in Andavadoaka.

Illustrations by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Transferring these monitoring skills to a local team also places the responsibility for stewardship of these reefs completely in the hands of the local communities, and may even encourage other community members in Andavadoaka and elsewhere in Madagascar to develop their own ideas and plans for future research and management. In this case, the pandemic brought about a fundamental change in the way that critical data for managing fisheries are collected and shared and has placed the local community firmly at the heart of the scientific as well as the management process. ‘Marine conservation is extremely important to my future,’ commented Ronaldo, a member of the new monitoring team. ‘If we can increase the number of fish, it will be easier for the Vezo people to live here in a more sustainable way.’

Critically, Blue Ventures’ teams have seen that alternative livelihood initiatives, such as their seaweed and sea cucumber farming programmes in Madagascar, can increase local resilience to economic shocks. The NGO and its partners also support the establishment of low-tech community-led savings and loans groups, which enable people to save money and access credit in remote areas where there are no banks. These have provided a buffer against financial difficulties. More diverse livelihood options and greater financial security are some of the many ways in which rural communities can become more resilient and better placed to face future challenges.

Illustrations by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation

These stories illustrate the many ways in which the global pandemic has impacted the oceans, the lives of coastal communities and marine conservation efforts. The intimate links between the well-being and livelihoods of coastal communities and the state of our oceans have never been more apparent. The absence of human disturbance is undoubtedly beneficial for marine wildlife and habitats.

But conservation is costly and in many places is reliant on philanthropy and Western visitors. The pandemic has revealed the fragility of some existing conservation models and has motivated organisations and communities to rethink their dependence on a limited range of options for funding and livelihoods. Rather than simply having provided a brief respite for wildlife, perhaps Covid-19 will bring about a whole new approach to monitoring, managing and protecting our oceans. Local communities and visitors can clearly be drivers of positive change, but innovation and creativity will be needed to build new conservation approaches to withstand whatever challenges the future brings.

Find the magazine online here or purchase Issue 11 of the Save Our Seas Magazine online here

Illustration by Lizzy Stewart | © Save Our Seas Foundation