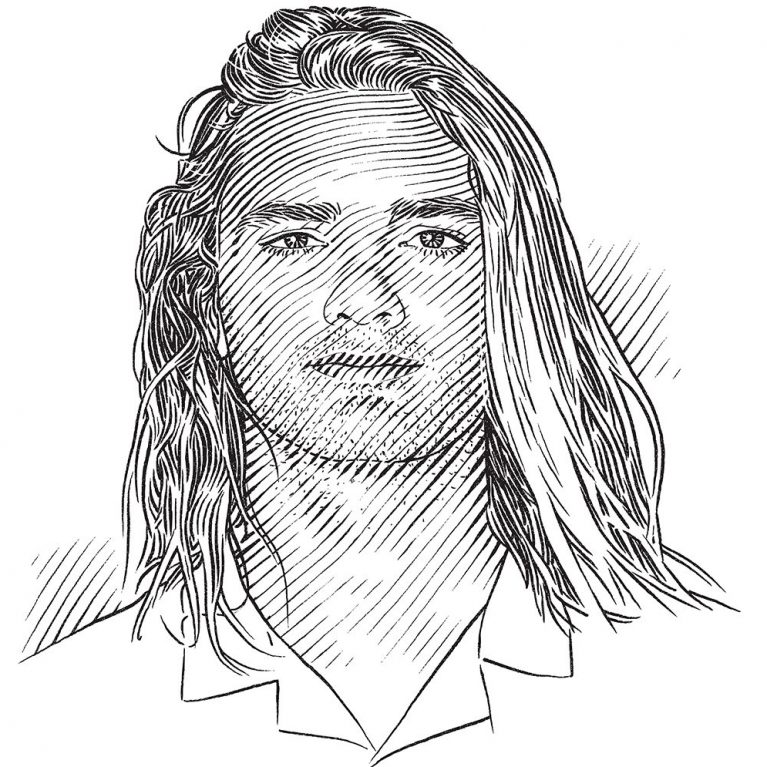

Kye Adams

Who I am

I’m a professional ocean lifeguard and marine ecologist from Australia. I live on a street called Beach Road, which I suppose is a nice metaphor for my obsession with the sea. This obsession probably stems from my father, also a great ocean lover, who named me after the Hawaiian word for ocean. Pretty much all aspects of my life have an obvious connection with the sea and I find myself getting anxious when separated from the salt water for more than a few days. I grew up surfing and diving in the small coastal town of Kiama, on the south coast of New South Wales. I started lifeguarding straight out of school, a job that has taught me great respect for the ocean. When I’m not lifeguarding, I film, catch and tag sharks and rays as part of a collaborative project with the Department of Primary Industries that looks to conserve coastal shark and ray species.

Where I work

I spend most of my time in or on the Pacific Ocean, along the south-eastern coast of Australia. I work with the seasons and spend a fair chunk of summer staring out to sea, keeping track of the tides, waves and currents and the people who enter the ocean for enjoyment. I love that the ocean is so wild and that despite our best efforts we are yet to tame or even fully understand her. Regardless of what many people may think, the most dangerous thing in the ocean is water, not sharks. In Australia, the ocean claims close to 100 people a year due to drowning, whereas shark incidents claim fewer than five. There is a growing movement towards sustainably managing shark populations, given the inherent vulnerability of most sharks (dangerous or not) to exploitation. As lifeguards, my colleagues and I can proactively prevent drowning by providing safe swimming areas, yet it is frustrating that at present we are unable to adequately prevent shark incidents. The effectiveness of the current strategy of mesh netting to catch and kill sharks remains highly contentious: it is indisputable that shark nets have high levels of by-catch and the level of safety they provide is unknown.

What I do

Our main focus at the moment is to find a sustainable alternative to shark netting, which is primarily designed to catch and kill sharks (by drowning them). Based in the small coastal township of Kiama, we run a grass-roots shark spotting programme designed to provide continuous coverage of an area used for swimming or surfing. Our blimp-mounted camera system provides a high-definition aerial view to observers. In partnership with Kiama Council, we aim to provide adequate warning to beach users when sharks and other hazards are present in their vicinity. The advantages of a blimp are that there is no by-catch and that it can stay up all day to provide a continuous watch for sharks. Traditional drones may also prove useful for shark spotting, but they tend to have a short battery life that may restrict them to responding when a shark is spotted rather than providing continuous coverage. We are testing what environmental conditions the blimp could prove useful in for shark spotting, and by deploying shark analogues we are developing a shark spotting rate. This spotting rate can directly translate into an increase in swimmer and surfer safety, rather than providing a false sense of security. With further testing, and support from the Save Our Seas Foundation, we hope to conserve sharks by providing a zero by-catch alternative to mesh netting and still prevent shark incidents.