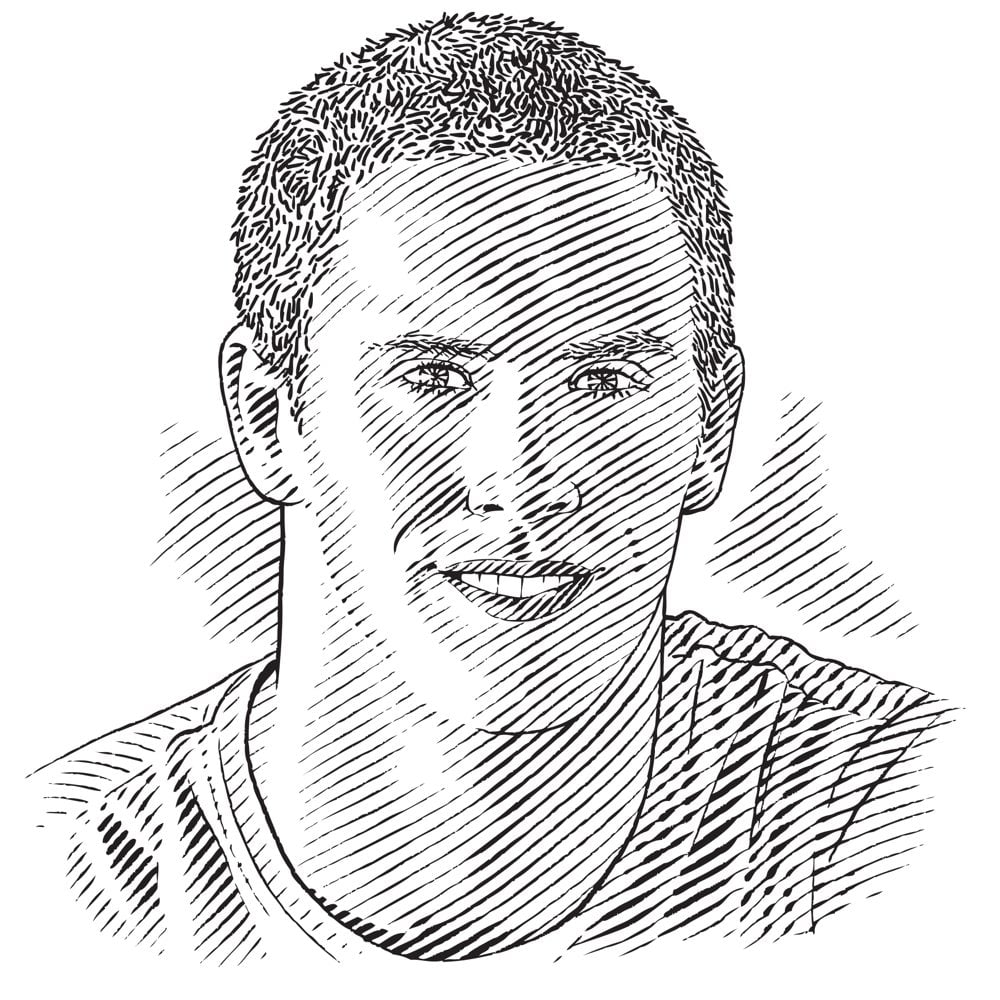

Charlie Huveneers

Who I am

Although I am originally from Belgium, which has only a 60-kilometre coastline, I have always been attracted to the ocean. My homeland’s marine fauna and flora may not be renowned for bright colours or amazing diversity, but they were enough to spark an interest in the underwater world that has become a lifelong fascination.

My specific interest in sharks started when I was 11 years old. Our teacher asked us to do a presentation on an animal, and while most of the children did theirs on cats or dogs, my mother suggested that I do mine on sharks. She bought me a book about them, which ended up being the catalyst for my passion for these magnificent creatures. The scientific editor of this book was Dr John D. Stevens, with whom I tagged sharks off north-western Australia 18 years later. Little did I know as an 11-year-old kid that I would one day work with one of the editors of the book I was reading.

Seventeen years after this presentation, I achieved one of my biggest goals by taking up a position as a shark ecologist at the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) and Flinders University in South Australia, where I formed the Southern Shark Ecology Group (SSEG). Not only had I successfully secured a highly sought-after position, but the journey to it had taken me to some amazing locations and experiences.

After high school in Belgium, I participated in an exchange programme with the Rotary Club that allowed me to experience Australia for the first time. Thanks to having learnt English during my exchange year, I was able to enrol at an English university and completed my undergraduate degree with honours at the University of Southampton. While studying and in the following years I volunteered for various shark-related projects that gave me an introduction to research. They included studies on basking sharks in England; pelagic sharks in the Gulf of Mexico; lemon sharks in the Bahamas; white sharks in South Africa; requiem sharks and leopard sharks in Queensland; and grey nurse sharks in New South Wales (NSW).

In 2002 these experiences and my degree helped me to get an international scholarship for a PhD at Macquarie University, Sydney, on the biology and ecology of wobbegong sharks in relation to the commercial fishery in NSW. Next, with SARDI, I investigated the diet and trophic role of pelagic species and used satellite technology to follow their movements and migrations.

By 2007 I was running the Australian Acoustic Tagging and Monitoring System, which involved deploying acoustic receivers around Australia and creating a national network of acoustic telemetry users. Two years later I was offered the joint positions of shark ecologist and lecturer at SARDI and Flinders University.

I have received seven scientific awards and am an active member of the IUCN’s Species Survival Commission’s Shark Specialist Group, for which I have co-authored more than 60 Red List assessments. I’ve written or co-authored numerous other publications, including peer-reviewed papers, reports and scientific presentations. The SSEG group has undertaken a wide range of studies, many of which involve white sharks and genetic analyses. Some of the key projects have been assessing the effects of berleying (also known as chumming) on white shark movements; monitoring threatened, endangered and protected shark species and species of conservation concern within the Adelaide metropolitan region; assessing the efficiency of the Shark Shield and its risk to white sharks; and determining the critical habitats and movement dynamics of the bronze whaler off southern Australia.

Where I work

Over the past few years Australia has gained the dubious distinction of having the largest number of fatal shark attacks in the world. The fear of sharks and in particular of the great white shark, the species that has been responsible for most fatal attacks, has resulted in a much public angst and a political backlash that has seen the promotion of control measures such as culls, beach netting and the hunting of individual sharks deemed to be responsible for attacks. Much of this debate has been fuelled by the uncertain status of white shark populations since their protection in the late 1990s. Proponents of culls suggest that numbers are increasing, but there is little scientific evidence to confirm or refute this idea. This offers an opportunity for emotive and unsubstantiated views to be promoted in the media and to influence political decisions on the future of this species in Australian waters.

What I do

Our project addresses directly the question of fluctuations in the size of the Australian population of great white sharks. We will examine evidence for changes in the effective population size based on genetic comparisons of historical and contemporary samples. Jaws of great white sharks have been collected as trophies by fishermen for many years. We will use these historical collections (we have identified more than 100 jaws in both private and public holdings) to estimate the effective population size before white sharks were protected.

Contemporary samples collected as part of our tagging studies will enable us to assess changes in the population size. Our aim is to provide robust estimates of population trends in great white sharks so that the debate about the status of this species and the options that are being considered to manage it are based on scientific evidence rather than only on emotion.