Playing with protection

The joy of nature is something all children should experience. But in today’s world, they will also encounter something other than nature: anxiety and a deep sense of responsibility for its future. Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Education Centre (SOSF-SEC) has a challenging but important role to play in raising awareness of the threats to our oceans, while instilling a sense of hope and wonder in young hearts and minds.

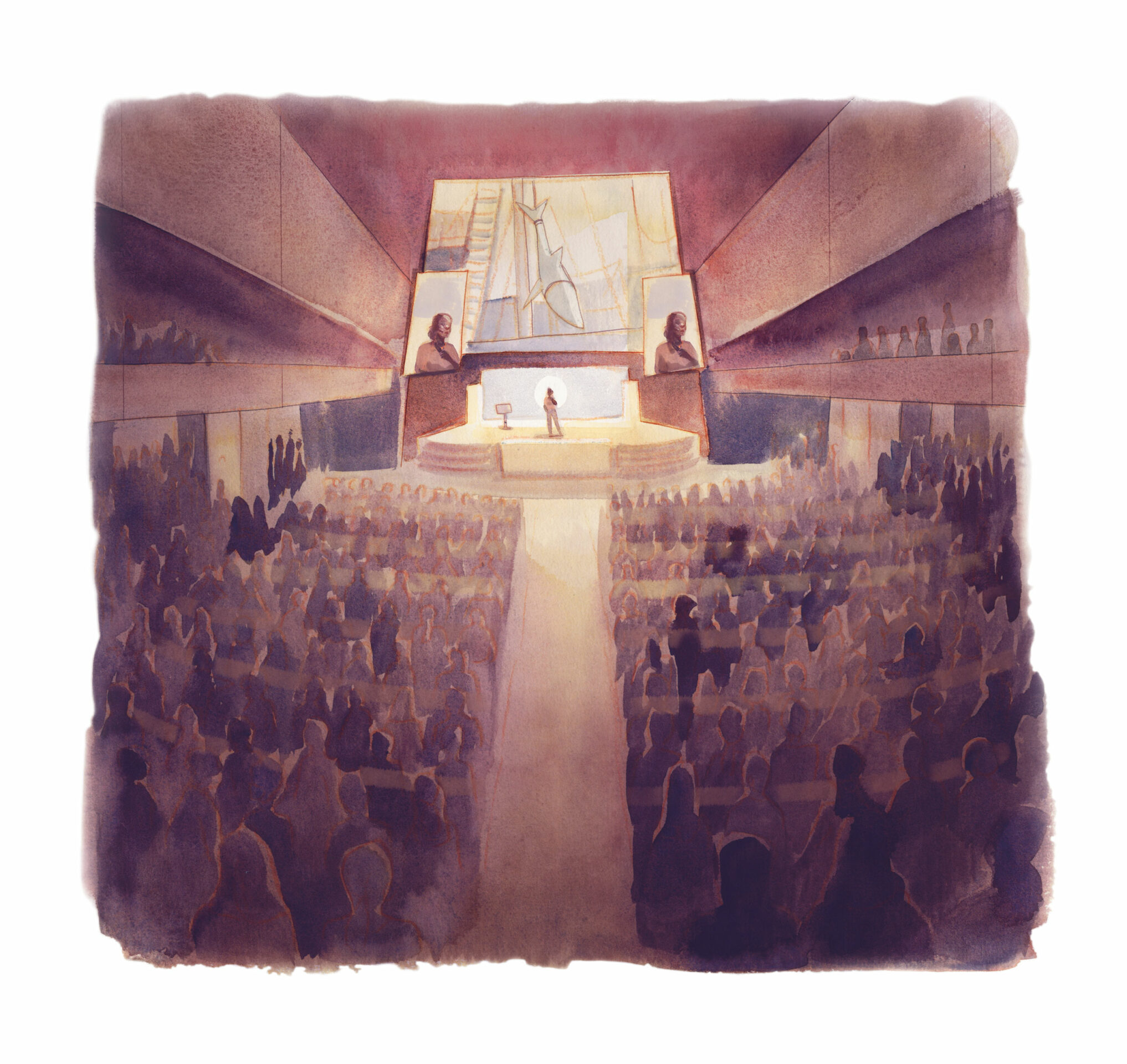

At a plenary session during the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP27, the delegation of Ghana requests the floor. But the voice that follows is not that of an official. It is 10-year-old poet and activist Nakeeyat Dramani Sam. Alone in a sea of business attire and faces much older than her own, she addresses those in attendance with an incredible composure that belies her tender age. She speaks softly but powerfully, her words direct. ‘There’s less than 86 months before we hit 1.5 [degrees Celsius]. And I’m already much older than that. So dear people at this COP – I appeal to you. Have a heart and do the math. It’s an emergency.’

Illustration © Rebecca Traunig

Watching this play out through a screen on the other side of the world, I feel a complex mixture of emotions. I am in awe of Nakeeyat and others like her who, before they have even finished school, are fighting to be heard on an international stage. Following in the footsteps of Vanessa Nakate and Greta Thunberg, youth across the world are taking the baton early; tired and frustrated by political inaction, they are stepping up to the plate to safeguard nature and their own futures. This brings me hope, but also great sadness. I can’t help thinking of my younger self, at the turn of the millennium, when my relationship with nature was one of sheer joy and exploration. Terms like ‘climate change’ and ‘ecological catastrophe’ were not part of my vocabulary. Thoughts of losing the species I had come to know and love never crossed my mind, nor did the possibility that extreme weather events would eclipse the seasons. My peers and I would never have dreamed of squaring up to a politician or stepping out of school to strike. But we didn’t have to. For the young people of today, the awe and wonder of the natural world is being eclipsed by a much darker reality: we are hurtling towards climate breakdown at alarming speed, and those in power aren’t reaching for the emergency brake. It’s a dawning realisation that director of the SOSF Shark Education Centre, Dr Clova Mabin, recognises on the faces of their students: ‘the look they get…it’s just shock. They’ve seen something so beautiful, and then it might be taken away.’

The term ‘eco-anxiety’ was coined in 2017 by the American Psychological Association to describe the chronic distress related to worsening environmental conditions. In the five short years since, reports have shown worrying increases in the number of children and young people experiencing eco-anxiety. A 2021 survey of more than 10,000 people aged 16 to 25 showed 75% feared for their future, and just under half reported that negative thoughts related to the environment impacted their ability to function normally. Another survey conducted in 2020, this time with child psychiatrists in England, showed that more than half of their patients were suffering with the condition. For the first time, children are inheriting not only the joy of nature, but also a sense of responsibility for its rescue. So how do we introduce them to the natural world with the appropriate capacity for both play, and protection?

Illustration © Rebecca Traunig

FORGING A CONNECTION TO THE SEA

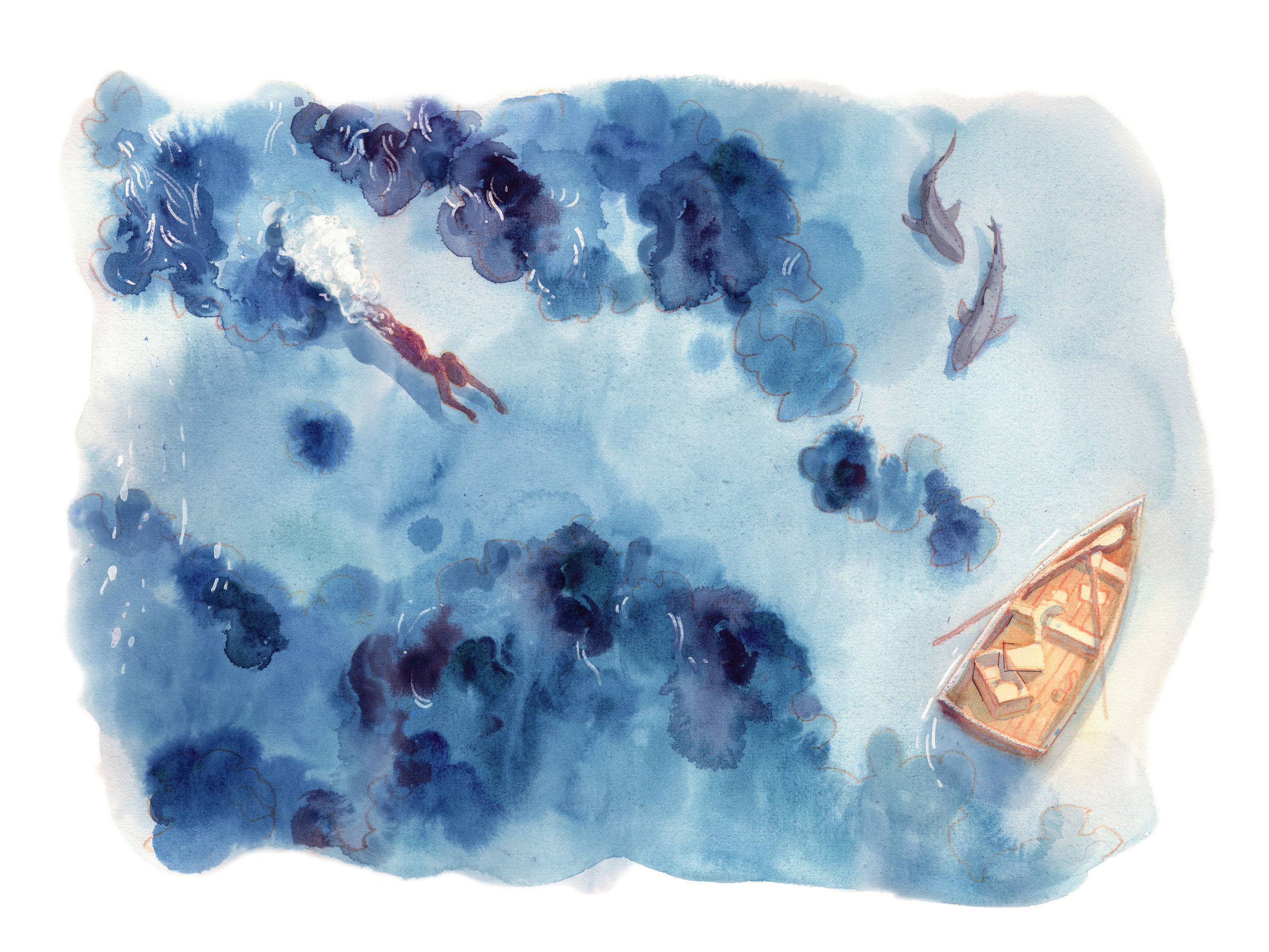

Nestled among the brightly coloured houses and vibrant coffee shops of South Africa’s Kalk Bay, the SOSF Shark Education Centre overlooks the Atlantic Ocean, across the legendary False Bay to the Hottentots Holland mountains beyond. There couldn’t be a more perfect location for a centre dedicated to connecting the public with marine life. Right outside the door lies the Dalebrook Marine Protected Area (MPA), a sanctuary zone within the greater Table Mountain National Park MPA. This hugely biodiverse rocky reef forms the setting for many of the centre’s activities. Students are taken on ‘treasure hunts’ to the rock pools at low tide to discover the animals hiding within them. They are taught to snorkel above the reef itself, watching the kelp fronds sway and spotting for sharks, or surf in the sheltered bay, learning about the tides and currents. In nurturing a love and fascination for the underwater world, Clova and her team can then encourage behaviours to protect it.

Nestled among the brightly coloured houses and vibrant coffee shops of South Africa’s Kalk Bay, the SOSF Shark Education Centre overlooks the Atlantic Ocean, across the legendary False Bay to the Hottentots Holland mountains beyond. There couldn’t be a more perfect location for a centre dedicated to connecting the public with marine life. Right outside the door lies the Dalebrook Marine Protected Area (MPA), a sanctuary zone within the greater Table Mountain National Park MPA. This hugely biodiverse rocky reef forms the setting for many of the centre’s activities. Students are taken on ‘treasure hunts’ to the rock pools at low tide to discover the animals hiding within them. They are taught to snorkel above the reef itself, watching the kelp fronds sway and spotting for sharks, or surf in the sheltered bay, learning about the tides and currents. In nurturing a love and fascination for the underwater world, Clova and her team can then encourage behaviours to protect it.

Fostering this connection is especially important considering that many of the kids enrolled in the centre’s programmes do not have access to the ocean, despite living in close proximity. Students who live as little as three kilometres away have often not seen the sea, let alone swum or snorkelled in it. Although Kalk Bay itself is considered an affluent neighbourhood, Cape Town and the surrounding areas still experience vast socio-economic inequality. Many of the children and young people who come to the centre

do not have running water, electricity, or a reliable source of food. ‘Some of them aren’t sure where their next meal is coming from,’ Clova explains. ‘I remember one of the first high schools we worked with…the kids were falling asleep at their desks. We were wondering what was going on. It was the first lesson of the day, surely they couldn’t be tired already? When I spoke to the teacher, she told us that they likely hadn’t eaten anything since the school meal the previous afternoon. It was a big reality check.’

In this way, the centre provides something more than just education: a refuge. For people from all walks of life, the ocean can be a distraction from life’s stresses, a place of peace. Experiences at Dalebrook have helped some of the centre’s students overcome grief, combat fears, and feel joy. Clova smiles as she remembers the beaming face of a young girl who tackled her fear of the water and swam for the first time, donning a mask and snorkel and exclaiming at the beauty beneath her. ‘I think for everyone, there’s something meditative about being in the ocean and controlling your breathing. It’s not something most children are taught at home. The slow controlled breathing, alongside something as magical as ocean immersion allows them to escape from their everyday lives.’

THE POWER OF PLAY

Once that connection has been established, the door is open for learning. We know from the fields of education and human developmental research that play is integral to a child’s ability to retain information – and at the SOSF Shark Education Centre, having fun is key, no matter what your age. ‘I think the power of play is underestimated, especially as you get older,’ says Clova. ‘Who doesn’t want to learn through play? It’s much more fun! And when you’re having fun, your mind is more open to new ideas and new concepts.’

For example, when it comes to teaching schools about the rocky reef at Dalebrook, Clova asks them to role-play. Some students become the animals, adopting their behaviours. Others become the waves and the wind, moving the others about like pawns on a chessboard. And one is always the sun, standing tall and holding aloft a bright light. ‘It’s putting them into situations where they’re really experiencing it, at a level they never have before.’ Other games include shark bingo and a marine version of twister (which, personally, I’m dying to play).

But aside from cool species of shark and ocean processes, students must also inevitably learn about the complex issues facing the very ecosystem they’ve come to love. Can this be achieved through play, too? Clova tells me about one of her favourite online games, called Survive the Century, created by Sam Beckbessinger, Christopher Trisos and Simon Nicholson. Described as a ‘branching narrative game’, players are walked through various scenarios representing the political, environmental and social choices humans will have to make within the next 100 years. ‘It’s a more gentle approach, because there are no real consequences, but they still understand the urgency of the situation,’ Clova explains. ‘And it allows them to see that their actions can make a real difference.’

BALANCING RESPONSIBILITY WITH HOPE

For the children and young people that Clova works with, eco-anxiety is uncharted territory. With so much else on their plate, the environment doesn’t yet feature much in their day-to-day life. But it will become a problem in the near future, especially given the importance of the ocean to their mental health: ‘they might feel like the thing that is going to help them is being taken away’.

We can’t shy away from the issues facing our oceans, or indeed the threats to the very futures of the next generation. But we can be conscious of how we deliver that message. At the SOSF Shark Education Centre, Clova says, building ‘constructive hope’ is vital. ‘We talk about the positive things that are happening, where there are improvements. And we give clear calls to action – realistic things that they can achieve. That’s really important, to make them feel as though they’re capable of doing something.’ These calls to action must be appropriate to their target audience – for instance, recycling centres are not available where lots of the kids live. But, while at the centre, they can get involved in beach and river cleans. ‘That adds the community feel to it as well,’ Clova continues, ‘which is also important in terms of them feeling they’re not alone.’

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Up until now, the SOSF Shark Education Centre has focused on its shortand medium-term programmes. These include the ‘Marine Explorer’s’ programme and half-day interactions, where schools could visit the centre and learn of sharks and rocky shores. More recently, a 10-week programme was established to give kids a real foundation in snorkelling, alongside ‘Sea School’, an after school club dedicated to marine education. But Clova wants to build on that. Her vision for the centre’s future is very much rooted in the long-term. Eventually, she’d like to be able to follow a group through school, nurturing their skills through time and

Up until now, the SOSF Shark Education Centre has focused on its shortand medium-term programmes. These include the ‘Marine Explorer’s’ programme and half-day interactions, where schools could visit the centre and learn of sharks and rocky shores. More recently, a 10-week programme was established to give kids a real foundation in snorkelling, alongside ‘Sea School’, an after school club dedicated to marine education. But Clova wants to build on that. Her vision for the centre’s future is very much rooted in the long-term. Eventually, she’d like to be able to follow a group through school, nurturing their skills through time and

providing career advice at opportune moments. ‘I believe that’s where we’ll see real success. Those kids are going to have bright futures.’

One Shark Education Centre alumni is already on her way to that bright future. Logan, now an intern, began visiting the centre several times through another programme. She is now a trainee educator for the centre, and is applying to university to pursue her dream of becoming a marine scientist. She will be an inspiration for other children, like her, who visit the centre and fall in love with sharks, and the underwater world they call home.

I think back to Nakeeyat’s speech at COP27. Her message was one of grave warning, but also hope. She challenged world leaders to ‘kindly up [their] game’ and protect the futures of those like her. She urged richer countries to support climate-vulnerable nations, suffering disproportionately the effects of climate change, but lacking the resources to recover. The delegates hung on her every syllable. Upon her last word, the room erupted into a standing ovation. Just two days later, a groundbreaking agreement was passed to provide ‘loss and damage’ funds to more vulnerable countries. I like to think that Nakeeyat’s words, and those of many others before her, cut through the dryness and jargon and reminded world leaders of what was at stake: the very futures of the next generation. And, that other young people watched this and felt hopeful. That they saw they had the power to turn the tide, and the responsibility to protect nature was one that was shared between many.

As Clova says: ‘Some of them feel that because they’re children, they’re powerless. But people like Greta and Vanessa show just how powerful children can be. Their voices can be heard around the world. I think when we share the work that other kids are doing, and the impact they are having just by using their voice, then ours see that no matter their background they still have agency. They can still change the world. There is still hope.’