Plastic rain

There are many sources of plastic in our oceans, including the mountains of single-use plastic created in western societies, and lost and abandoned fishing gear. But far more insidious is the problem of microfibres, and it’s one that very few people are aware of.

Artwork © Drawii | Shutterstock

A recently published study has revealed that tiny pieces of plastic, fragmented from larger items, can be transported long distances from urban areas to protected lands and national parks, where they are deposited by rain and air currents.

Researchers collected rainwater and air samples from 11 protected areas in the western USA for 14 months, and analysed those samples. They calculated that over 1,000 metric tons of microplastic particles (tiny fragments plastic smaller than 5 mm in length) fall into these protected areas in the western USA each year. That’s the same as over 120 million plastic water bottles or, if you prefer to think in terms of marine animals, that’s the same weight as about eight blue whales! And that’s only what’s falling into their study area, which accounts for just 6 % of the USA’s total surface area.

What are microfibres?

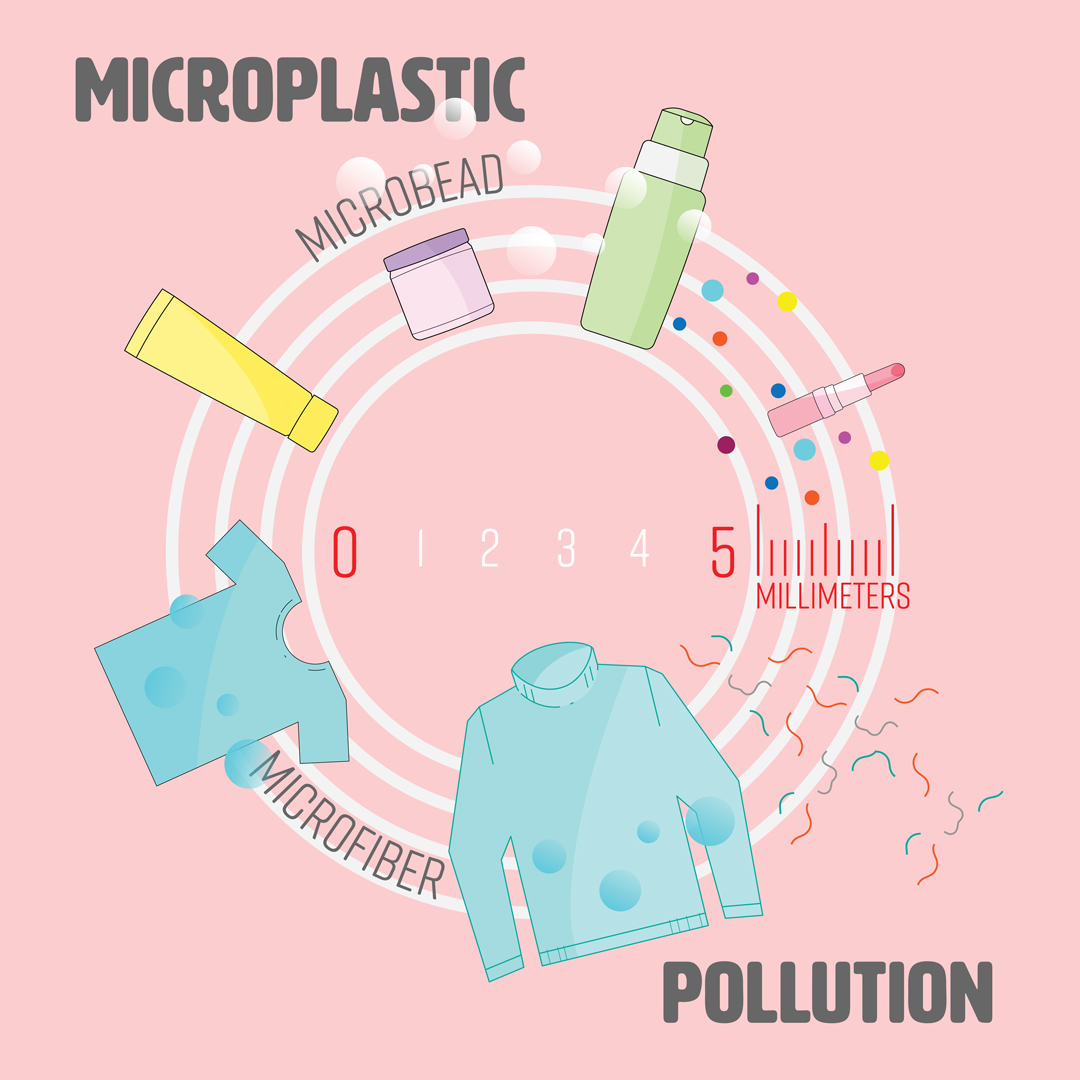

When we think of plastic pollution in the ocean, we may think of the discarded bottles, food packaging and other trash we see on a beach, or washed up fragments of fishing nets. But in fact, a recent report by the IUCN (the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) suggests that between 15% and 31% of marine plastic pollution could be from microplastics, released by household and industrial products.

Artwork © Drawii | Shutterstock

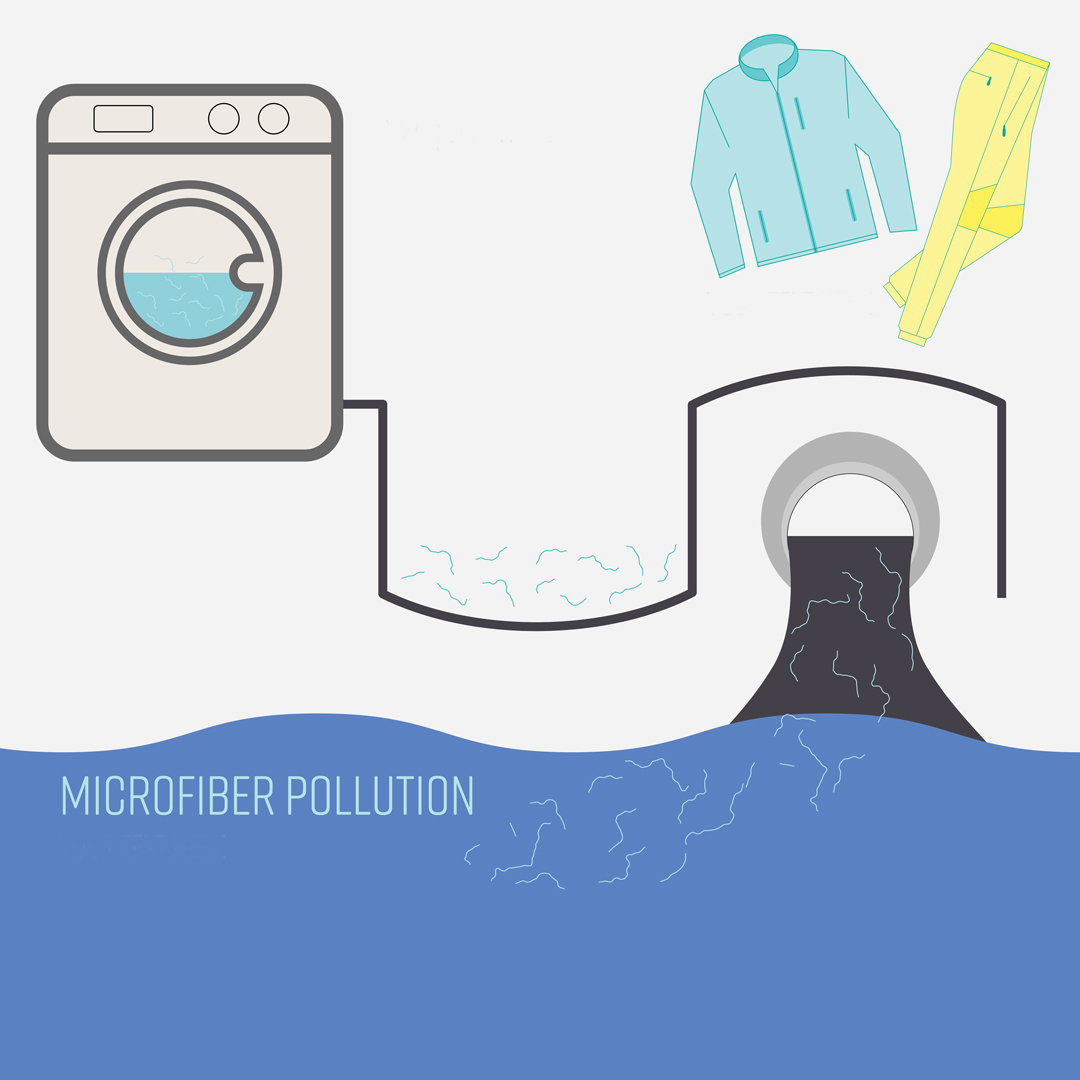

Did you know that clothing made from polyester, acrylic, nylon and other synthetic materials are essentially types of plastic? If you have sports gear and clothing, most of that is likely to be made of synthetic fibres. Rain jackets, many t-shirts, fleece sweaters, even the soles and uppers of trainers and other shoes – these and many more items are all made from synthetic materials. Some companies recycle plastic bottles to make polyester, and market the clothing made with this ‘repurposed’ material as somehow more environmentally friendly. But the truth is, it’s not.

When we wash clothing made from synthetic materials, very tiny pieces of that material, called ‘microfibres’, are released from the clothes and flow down the drain. As you might guess, microfibres are microplastics in the form of a fibre, with a diameter of less than 10 micrometres (that’s less than one-fifth of the diameter of a strand of human hair). Hundreds of thousands of these fibres can be released with each wash, and the older the clothes, the more microfibres they release. Washing machine filters and water treatment plants do not catch these fibres because of their tiny size, so they end up in rivers, lakes and the ocean.

Tumble dryer lint showing all the tiny microplastic fibres released when using a tumble dryer for clothes. For size comparison there is the point of a pin. Image © Scorsby | Shutterstock

How do these microfibres get into the rain?

Regional storms can pick up microplastics from the land, carry them for some distance and then deposit them, via wind or rainfall. This means that microplastics can now be found even pristine, uninhabited areas like national parks.

Why should we care?

When microfibres reach the ocean, they act like sponges, absorbing pollutants (like pesticides) in the water around them. They are then eaten by marine animals – microfibres have been found in fish and shellfish, sold for human consumption in California and Indonesia. This consumption of microplastics by marine animals may mean that the pollutants and chemicals absorbed by the plastics gets transferred into the animals’ bodies, with unknown consequences for their health and for the health of seafood consumers, like humans. The study’s authors also noted that as plastics continue to accumulate in wilderness areas, some species of animal may be more vulnerable than others to the physical and toxicological effects of consuming microplastics. This could cause some species to disappear, which would change the diversity and function of whole ecosystems. Another study found that ocean currents carry microplastic particles into deep-sea ecosystems, and when the currents slow, the suspended particles settle on the seafloor. Whether on land or in the ocean, the impacts of our plastic addiction are being seen in environments we previously thought of as ‘untouched’.

Artwork © Drawii | Shutterstock

How can you help?

We cannot all stop owning synthetic clothing overnight, and clothing companies won’t stop producing them either. But here are a few steps that can help you to address microfibre pollution:

- Use laundry bags like guppyfriend bag. Placing your synthetic clothing in one of these little bags before throwing your laundry in the machine reduces the amount of microfibres that each item sheds during a wash. The bag also catches all the fibres that are shed, and over time you can scrape those out of the bag and dispose of them with your rubbish. It’s not great to have plastics going into landfill, but rather there than the ocean.

- Colder wash settings and shorter washes mean fewer microfibres are released. They also use less water and energy, so they’re better for the environment!

- Whenever you have to buy new clothes, try to buy natural fibres wherever possible and avoid ‘fast fashion’ clothing, which tends to be less durable.

- Check out Story of Stuff who are demanding that clothing companies take responsibility for microfibre pollution.

If you’d like to learn more about microfibres, watch this short and easy to understand film, ‘The Story of Microfibers’.

Artwork © Drawii | Shutterstock