MPAs benefit biodiversity, but do they work for people?

Review collates evidence of economic benefits to fisheries and from tourism

On the coral reefs off Kenya’s coast, the blue, black and yellow hues of surgeonfish had started to fade. So too had the familiar yellow speckles as various types of rabbitfish were overfished, and the nightly predatory rooting of the emperor fish that ruled the reefs had dwindled. But after pull seine nets were eliminated and the waters protected, it appears that numbers of these famous reef-dwellers had not only increased inside the protected area, but ‘spilled over’ the invisible borders of the Mombasa Marine Park onto surrounding reefs. The result? Fishers started to report that their catches of the species in these families in the managed zones of the marine protected area (MPA) were increasing, both in the quantity of fish and the size of the individuals caught.

In a familiar refrain, the larvae produced by a bank of Australasian snapper fish protected in New Zealand’s waters ‘subsidised’ local fishers who had lost their fishing grounds to the declaration of an MPA. Those adult snappers contributed as much as 10% of the juveniles that settled in the area surrounding the Cape Rodney–Okakari Point Marine Reserve. Stories like this are echoed in studies of the waters off Vanuatu, South Africa, Spain, Mozambique, Hawaii, Mexico… And in the Isle of Man, where fishers claimed that scallop catches were higher next to the MPA and close to its boundary.

Each of these is a case study reviewed in a recent paper that concludes that MPAs are a useful fisheries management tool. These protected areas help to bolster the numbers and body sizes of various important catch species and improve not only the catches, but also catch-per-unit-effort, which is an indirect measure of fish abundance, usually calculated by dividing the number of fish caught by the ‘effort’ (number of hooks, hours of trawling) to catch them. MPAs also provide ‘spillover’ of healthy numbers of a population to improve the fish stocks outside their borders. So reports Mark Costello, the author of ‘Evidence of economic benefits from marine protected areas’, published earlier this year in the journal Scientia Marina.

Artwork by Ivan Colic | © Save Our Seas Foundation

MPAs work for biodiversity, but do they work for people?

Although MPAs have been used to conserve biodiversity for decades (with evidence of success and a fair amount of support), their economic success and the impact they have on areas outside the protected zones are hotly contested. Costello argues that this criticism of the usefulness of MPAs, particularly as a fisheries management tool, is hindering our progress when it comes to achieving conservation targets. While we debate the issue, he says, the economic and ecological integrity of our oceans is rapidly being eroded.

Costello reviewed 48 cases where economic benefits were reported to fisheries in 25 countries, and 31 cases where economic benefits as a result of tourism were reported in 24 countries. His search found no evidence of net costs to fisheries from the implementation of an MPA – anywhere. Instead, the review shows that the scientific literature hosts a bank of evidence that supports improvements in fish stocks, catch volumes, catch-per-unit-effort, fecundity (fertility or reproductive capacity and productivity), larval export and the body size of individuals.

When MPAs are well designed and enforced, says Costello, the evidence shows that they do provide economic benefits for fishing communities. They are, he argues, a key strategy to help us use the resources from our oceans sustainably.

A large school of yellowfin tuna working a baitball in the protected waters of Costa Rica. Photo © Christopher Leon

A review of the published scientific MPA literature

Costello set about gathering the published evidence of the economic benefits from MPAs by searching key words on Google Scholar. The first 200 records that came up from searching ‘economic’, ‘value’, ‘MPA’, ‘marine protected area’, ‘marine reserve’, ‘fisheries’ and ‘tourism’ were analysed.

In total, 51 MPAs were reviewed. Of these, 35% had been in effect for less than 10 years and 22% for longer than 20 years. Economic benefits were reported from 90% of MPAs and from 25 countries across the North Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific and Indian oceans. They included MPAs with varying methods of protection, from those that had multi-use zones and restrictions on gear types to no-take (fully protected) MPAs (which showed the strongest benefits). Benefits were also derived from MPAs that covered many types of ecosystems, from mangroves to kelp forests and mudflats, from rocky reefs to muddy sea beds and coral reefs. Three-quarters of the MPAs showed increases in fishery catches and 25% reported increases in fish body size.

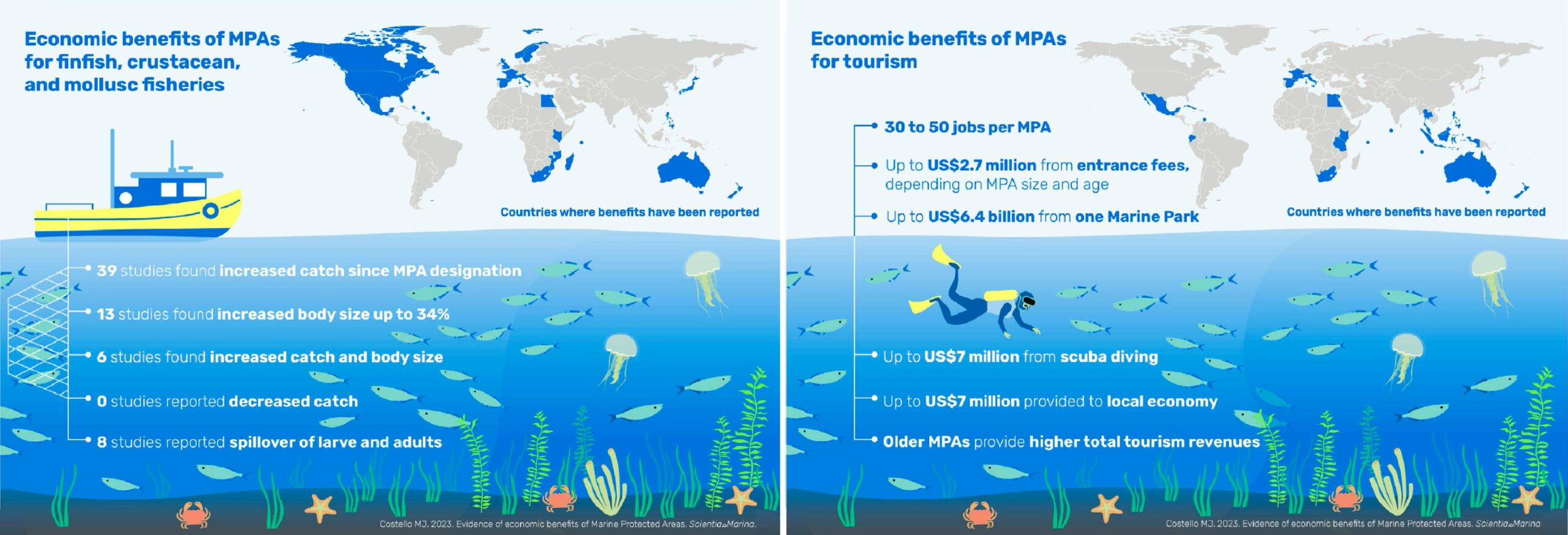

Economic benefits to fisheries of MPAs

- 39 studies reported increased catches

- 13 studies recorded that individuals increased in body size by up to 34%

- Six studies reported that both catch and body size increased

- Eight studies reported spillover of adults and larvae from MPAs into adjacent fishing areas

- No studies reported a demonstrated loss from the designation of an MPA

Can income also be generated inside an MPA, without taking anything out?

On South Africa’s balmy east coast, divers can come within two metres (6.5 feet) of tiger sharks. The experience helps to bring in US$885,000 annually to the Umkomaas region where the Aliwal Shoal MPA is situated. Travel further south along the coastline to the Wild Coast and the spectacle that is the annual sardine run brings sharks, dolphins, whales, seabirds and paying tourists to some of the wildest and least exploited reaches of the coast. Visitors pay what amounts to US$765,800 to participate in the annual sardine run, launching for boat-based dives and viewing between Port St Johns and Mbotyi in the Pondoland MPA.

In Seychelles, MPAs provided 31 jobs and 13 trainee positions, raking in US$135,324 direct revenue and US$8,000 operating profit. In Palau, shark diving brings in US$18-million, a startling contribution that eclipses the US$10,800 that would be derived from shark fishing.

With US$6.4-billion brought in from the Great Barrier Reef and US$7.4-million from the Medes Islands Marine Reserve in Spain, Costello reviews the idea that MPAs also generate economic benefits through non-extractive tourism activities. He found 31 examples from 24 countries in mostly tropical and subtropical regions that reported benefits from parks that comprised predominantly coral reefs, mangroves and sea-grass ecosystems (but the review also found MPAs that encompassed rocky reefs, sandy sea floors, kelp forests and mud bottoms).

Money can be made from non-extractive activities in MPAs through diving, transport, accommodation, user and permit fees, and goods and services. Older MPAs tended to attract most revenue, but dive tourism brought in US$739,200 in Spain’s La Restinga MPA and US$1,137,600 in the Bonafacio MPA in France, which were not among the oldest MPAs in the review. Shark diving, specifically, contributed US$650,000 annually in Fiji. User fees and ticket sales added US$500,000 to the coffers over the course of four years in the Ho Chan Marine Reserve in Belize, US$30,000 in the Tubbataha Reefs Natural Marine Park in Philippines and US$26,900 in the Malaysian Sugud Islands Marine Conservation Area.

Swimming with sharks and manta rays that frequent marine protected areas is a particularly popular tourist activity, and can generate considerable income for the region. Photo © Matthew During

Economic benefits from MPA tourism

- 30–50 jobs were reported per MPA

- Entrance fees brought in US$2.7-million, depending on the size and age of the MPA

- One marine park brought in up to US$6.4-billion

- Scuba diving in MPAs brought in up to US$7-million

- The local economy benefited by up to US$7-million

And what about the criticism?

Costello negates the critical views on MPAs being useful for fisheries by presenting a suite of evidence that shows that MPAs do increase fish stocks and fishers’ catch and contribute to spillover. ‘It may seem counter-intuitive that restricting fishing in an area will result in more fish elsewhere,’ he writes in the paper. ‘Yet, this happens because marine life disperses from its safe haven (the MPA), which acts like a reservoir to replenish adjacent fisheries. In financial terms, the capital is invested, and people benefit from the interest on the investment. To count MPAs as a cost to fisheries is analogous to claiming that interest earned on money is a cost. The evidence of this benefit is unequivocal.’

Instead, his view is that fisheries and fishing communities actually have much to gain from the proper implementation of MPAs. In some instances, the flow of those benefits might need redress or increase; for instance, Matt Dicken writes that while the sardine run brings in millions of rands (the local currency) to operators and accommodation in the region, local indigenous communities on South Africa’s Wild Coast seldom, if ever, benefit directly. It’s a critical point that is missing from Costello’s review: if there are benefits, who benefits and how? However, the overarching message of the review is clear: there is substantial evidence of the economic benefits emanating from MPAs, both to fisheries outside and from tourism within. And, he concludes, business-as-usual simply isn’t working: we will need to consider an ecosystem approach to fisheries that includes MPAs as a management tool.

The reefs of the Marshall Islands' marine protected areas team with marine life. Photo © Sebastian Staines

A final word…

Costello raises the point that, once fisheries have reached crisis point, management already restricts, if not outright bans, catches of certain species at specific times of the year or in particular areas. The implementation of these measures, he argues, can cause far more devastating financial implications for fishers and fishing communities than an MPA would, particularly if that MPA allows for controlled fishing. We are, in a sense, he suggests, kidding ourselves that we are not doing worse than if we designed effective MPAs that are well funded, resourced and enforced for fisheries management. The point is not to replace all traditional fisheries management, but rather to better support how we derive economic benefits from MPAs.

**Reference:

Costello MJ. 2024. Evidence of economic benefits from marine protected areas. Scientia Marina, 88(1).

https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.05417.080