Mermaids’ purses

Have you ever found a mermaid’s purse on the beach? These little capsules can be cast upon the beach where they blend in well with strands of seaweed, so you need to be looking carefully to find one! Perhaps, in the past, some people believed that they were indeed purses or bags for the treasures belonging to a mermaid, but we now know that they hold very different kinds of treasure. Mermaids’ purses, also called eggcases, are in fact the protective cases inside which eggs develop into baby sharks and skates!

A developing dark shyshark inside its eggcase, photographed in False Bay, South Africa. This little shark can only be found in the cool waters off southern Namibia and western South Africa. Photo © Lisa Beasley.

Unlike most fish – which release their eggs and sperm into the open ocean and leave the rest to chance – sharks and their relatives (rays, skates and chimaeras) practice ‘internal fertilisation’, which gives their pups a much better chance at survival. The young (called pups) of all rays and some sharks develop in eggs that are within the mother’s body. Those eggs hatch inside the mother and are then born as miniature adults. All skates and some other shark species use a different approach – the females produce eggcases and attach them to something underwater or leave them on the seafloor. One or more pups develop inside each eggcase, then hatch and swim away.

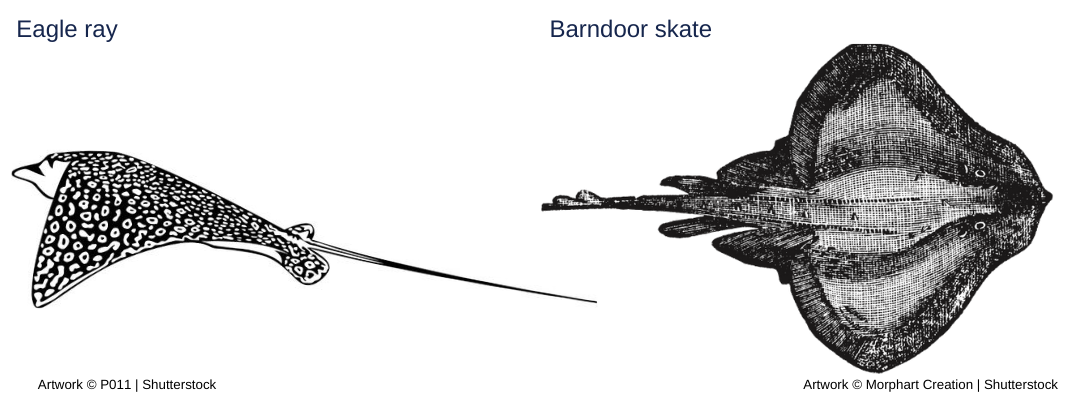

Not sure what the difference is between a skate and a ray?

Well, both are flattened fish related to sharks. The main difference is that skates produce egg cases, whilst rays give birth to live young. Rays also have two stinging spines on their tails, which they use to protect themselves, whilst skates do not. Artwork © Morphart Creation | Shutterstock and © PO11| Shutterstock

Eggcases can be simple or elaborate in design. They are made mostly of keratin (the same substance that your hair and fingernails are made of), making them strong but also flexible. Eggcases are usually pillow-shaped, with horns or long curly strands (called tendrils) at each corner. The eggcases of Port Jackson sharks and crested horn sharks are probably the most unusual – they have a corkscrew shape, and female Port Jackson sharks screw them into crevices in rocky sea floors, so they don’t get washed away. The Australian swellshark has perhaps the most beautiful eggcase – bright orange-yellow, with a frilled, ball-gown appearance.

Port Jackson Shark eggcase. Photo © Caroline Armitage | Shutterstock

Australian swellshark eggcase. Photo © Angela Heathcote.

Chimaeras (sometimes called ghost sharks or rabbitfish) are relatives of sharks and rays that live in the deep ocean. They also produce unusual eggcases which are spindle- or bottle-shaped with wide ridges along each side. They look a bit like spaceships!

A chimaera eggcase. Photo © Natural History Museum, London.

The time it takes for a baby skate or shark to hatch from its eggcase depends on the species. Researchers found eggcases of the Pacific white skate on the seafloor, 1,660 m deep, near hydrothermal vents (cracks in the seafloor that leak hot water and steam) off the Galapagos Islands. The skates may have chosen these warmer areas for their eggcases to help speed up the development of the pups. Deep-sea skates have some of the longest egg incubation times known for the animal kingdom – some species have incubation periods of 1,290 days at water temperatures of 4.4 °C. That’s over 3 years! But other species, like catsharks, hatch from their eggcases after just a few months.

Pacific white skate eggcases on hydrothermal vents. Photo by Ocean Exploration Trust | Nautilus Live Copyright.

Pyjama sharks live in the kelp forests of South Africa and get their name from their beautiful striped appearance! A pyjama shark pup may develop inside the eggcase for up to 5 and a half months before hatching.

A pyjama shark’s eggcase, suspended between two kelp stipes in False Bay, South Africa. Pyjama sharks have olive green eggcases that can be up to 10 cm long. © Helen Walne

Both dark shysharks and puffadder shysharks reach only 60 cm in length as adults, making them the smallest of the shark species in South Africa’s kelp forests. Shysharks are so called because they curl up with their tail over their eyes, when captured. Dark shysharks have very small eggcases which are amber to dark brown in colour, whilst puffadder shysharks have distinctive, striped eggcases.

This stripey eggcase attached to the spines of a sea urchin in False Bay, South Africa, belongs to a puffadder shyshark. Photo © Lisa Beasley.

The flapper skate is the largest species of skate worldwide – up to 2 metres across its wings – and lives in the northeast Atlantic, from Norway and Iceland down to Ireland and the UK.

Flapper skate eggcases can be up to 28 cm long - that’s longer than an adult human’s hand! Photo © The Shark Trust | Great Eggcase Hunt.

Thornback skates are found in the Eastern Atlantic from Iceland to South Africa, and in the Mediterranean Sea. Their eggcases are black and can be up to 12 -15 cm long.

Lottie Fitzsimons, 5 years old, with a thornback skate eggcase from a beach in Ireland. Photo © Aoibheann Leeney.

How can eggcases help us learn more about sharks and skates?

Sharks, skates and chimaeras move around a lot, which means it can be difficult to pinpoint specific areas inside which we can give them protection. If we record where we find eggcases, then we at least know which areas are important for unborn sharks, skates and chimaeras. By protecting those areas, we can give many of these species a better chance of hatching and making it through the first few challenging days or weeks of their lives.

If you are lucky enough to live near the sea and want to go in search of mermaids’ purses yourself, look at the high tide line, where bands of seaweed have been left by the tide. You need sharp eyes to notice the eggcases amongst the seaweed! Many organisations around the world encourage citizen scientists to send them information about the eggcases they find, so check to see if there’s one where you live. Be sure to take photos of your eggcase and record where and when you found it. The next time you find an eggcase, take a closer look and imagine the tiny shark or skate that spent the first few weeks of its life inside!