Manta Rays are no longer mating, and it’s a problem

Recently, Guy Stevens and his team were visited by a reporter from the Guardian newspaper who came to the Maldives to find out why the Maldivian mantas have stopped breeding. Below is his story:

http://mg.co.za/article/2013-10-07-manta-rays-are-no-longer-mating-and-its-a-problem

The gentle, plankton-eating giants seem reluctant to mate in water lacking the nutrients needed to support life.

"Mantas!" shouts Guy Stevens from the top deck, pointing to huge bat-shaped shadows gliding under the rippling, turquoise water of Hanifaru bay in the Maldives.

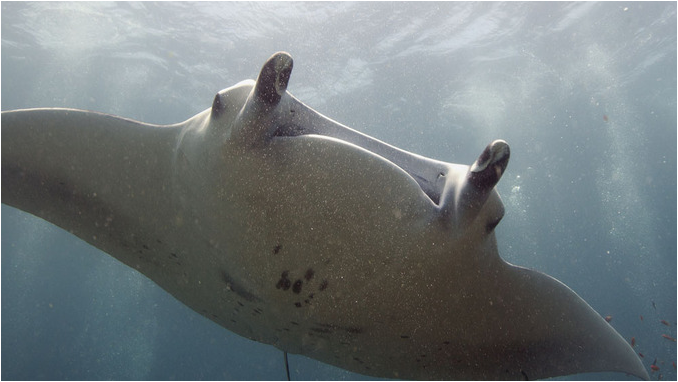

Moments later his team are free-diving below the huge rays, which undulate their black and silver wings to sail over the special reefs where they can pick up cleaner fish to preen their skin.

The divers surface beaming, having photographed the unique patterns of dots and dashes on the white underside of the 3m-wide rays that are used to identify and track the gentle, plankton-eating giants.

Mantas are protected in the Maldives and had been faring relatively well, compared with populations in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and elsewhere, where thousands of the inquisitive creatures are slaughtered each year to supply the Chinese traditional medicine market.

But Stevens is worried by a new threat.

Usually about a third of the females are pregnant every year, he says: "But then – boom – in 2009 reproduction just stopped."

"Is this part of long-term natural cycles or is it something more sinister, related to climate change and human impacts?" asks Stevens, founder and chief executive of the Manta Trust, which runs its Maldives programme from the Four Seasons resort on Landaa Giraavaru island, with the company funding the trust’s staff and operations.

"I suspect it is not natural," he says.

"The meteorological people say the monsoon is changing [from usual patterns], and the fishermen who have been out there for 50 years say it is definitely changing."

Stirring up the seas

Stevens has been tracking the Maldive mantas for eight years and has 15 000 sightings of 1 500 individuals from the last four years alone.

Their feeding events correlate closely with the average speed of the winds, which have been blowing less strongly overall in the past four years.

Weaker winds are less effective at stirring up the seas, meaning the nutrients needed for plankton to bloom are missing.

"If primary production is affected, that passes up through the food chain and affects the mantas," he says, adding that mantas bring in about $20-million a year in tourism revenue for the Maldives.

Low rates of reproduction

Mantas have very low rates of reproduction – just a single pup every two to three years – meaning they are very vulnerable to anything that cuts the number of births.

Stevens says they appear to be choosing not to breed when food is scarce: "They need to be sure the big investment of energy will pay off as they don’t get many chances."

The link between food supplies and the barren past four years is also supported by satellite measurements of chlorophyll in the sea in the Maldives, another measure of plankton productivity.

"For the last four years, instead of a nice green sea, we have seen empty blue seas," says Stevens.

There is, however, a glimmer of hope, he says: "For the first time in four years we have now seen some mating behaviour and the associated injuries" caused by the males biting the backs of the females during mating.

The numbers are low, just two dozen compared with about 200 normally, and it is too early to tell if the tide has turned for manta reproduction in the Maldives, he says.

Back under the water, divers Moosa Mohamed and Niv Froman have made a discovery: a small, 1.5m-wide manta with a pure black, velvety back.

It is a juvenile but probably more than four years old.

Later that evening the youngster is confirmed as a new animal and it joins Steven’s database, having been christened Batmanta. – guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media 2013

SOURCED FROM THE MAIL AND GUARDIAN