GALÁPAGOS: An evolving oceanscape

Deep below the Nazca Plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean, the writhing earth’s crust has belched molten lava for more than 20 million years. These geological dramas gave birth to the Galápagos Archipelago, a collection of islands that have clawed their way to the sea’s surface over millennia. Today they rise as craggy shield volcanoes and lava piles scattered across 59,500 square kilometres (23,000 square miles) of ocean. First named ‘Las Encantadas’ (The Enchanted) in 1535, the Galápagos Islands and their treasure trove of life keep us enthralled. Photographers, natural historians and conservation scientists are still finding new ways to see these islands and the ocean around them, more than 180 years after Charles Darwin first penned The Voyage of the Beagle and formed the basis of his theory of evolution that would become On the Origin of Species.

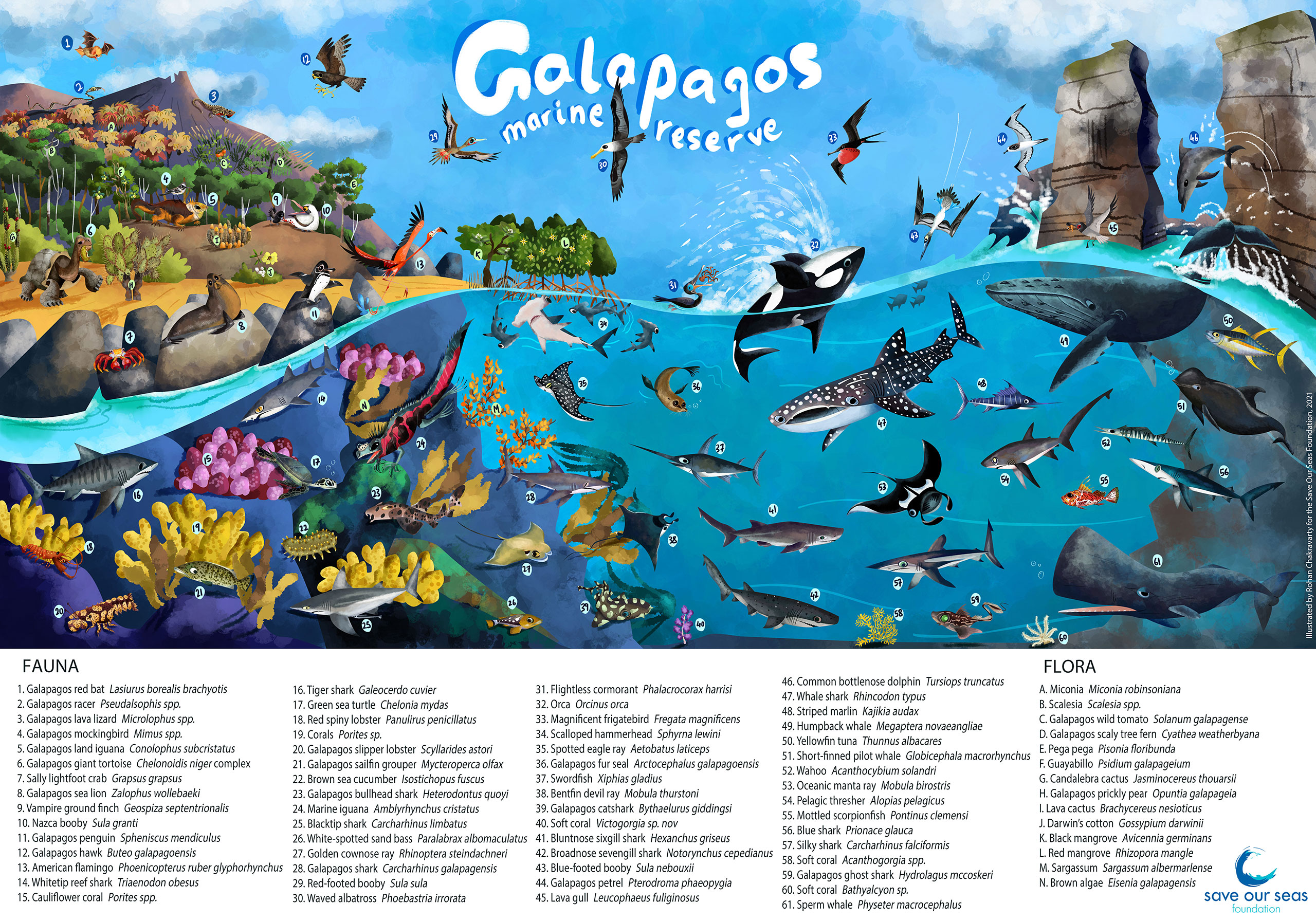

The geographical wonders of this archipelago extend far beyond the ocean surface. These islands house a multitude of diverse habitats that are able to sustain life for a vast, varied number of species. They are located at the confluence of three ocean currents, making them one of the world’s richest marine ecosystems.

Charles Darwin’s voyage to the Galápagos Islands aboard The Beagle in 1835 marked a critical moment in Western History. Darwin spent five weeks scouring the islands, collecting specimens, documenting his findings, and searching to understand further what he had observed during his time there. The sights and creatures he encountered, giant tortoises, free-diving iguanas, and incredible diversity of bird species, formed the basis of his theory of evolution that would become On the Origin of Species.

Photo © Chris Vaughan-Jones

Photo © Chris Vaughan-Jones

In 1959 the Charles Darwin Foundation was established, the same year the government of Ecuador created the Galapagos National Park. However, the island began to suffer in the 1970s as agriculture and pollution became more prevalent, highlighting the need for protected areas. In 1974, the Terrestrial Management Plan of the National Park was written and recommended protecting two nautical miles of sea around each of the area’s 19 main islands. In 1998, this marine protection was reinforced when Ecuador created an MPA which included all areas 40 nautical miles from the islands’ coasts, as well as their inland waters (lagoons & streams)

In 2016, Wolf and Darwin Islands, an area that covers over 38,000 square kilometres (15,000 square miles), located in the northwest of the Galapagos Archipelago, was identified as having the largest shark biomass on the planet by scientific researchers from the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF).

Despite the waters seemingly teeming with wildlife, the study also found that reef fishes around this area, such as groupers, were still experiencing reduced numbers due to unsustainable fishing practices. This highlighted that the work to protect the critical species of the Galapagos is still far from being completed.

Photo © Pelayo Salinas

Illustration by Rohan Chakravarty | © Save Our Seas Foundation