Feeling the heat

Across Europe, 2019 brought record summer temperatures, followed by dramatic scenes of bush fires across Australia at the close of the year and into early 2020. According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, the global land and ocean surface temperature in January 2020 was the highest in the 141-year record. In early 2020, temperatures across the western Indian Ocean, including the east coast of Africa, were between 1 and 2 degrees warmer than usual for the time of year.

Shallow tropical coral reefs are very biodiverse, many different kinds of corals grow in different forms, and have different functions. They provide habitats for all kinds of ocean animals, as well as food, coastal protection from storm surge and battering waves, jobs, tourism and recreation for people. Photo © Umeed Mistry | Coral Reef Image Bank

It’s not just people and life on land that suffers when the temperature soars. The ocean warms too, and as it does so, it can stress and negatively affect the health of marine life. But while mobile animals like sharks can move into cooler waters by diving deeper or moving away from the equator, what about the underwater life that cannot move?

What is coral bleaching?

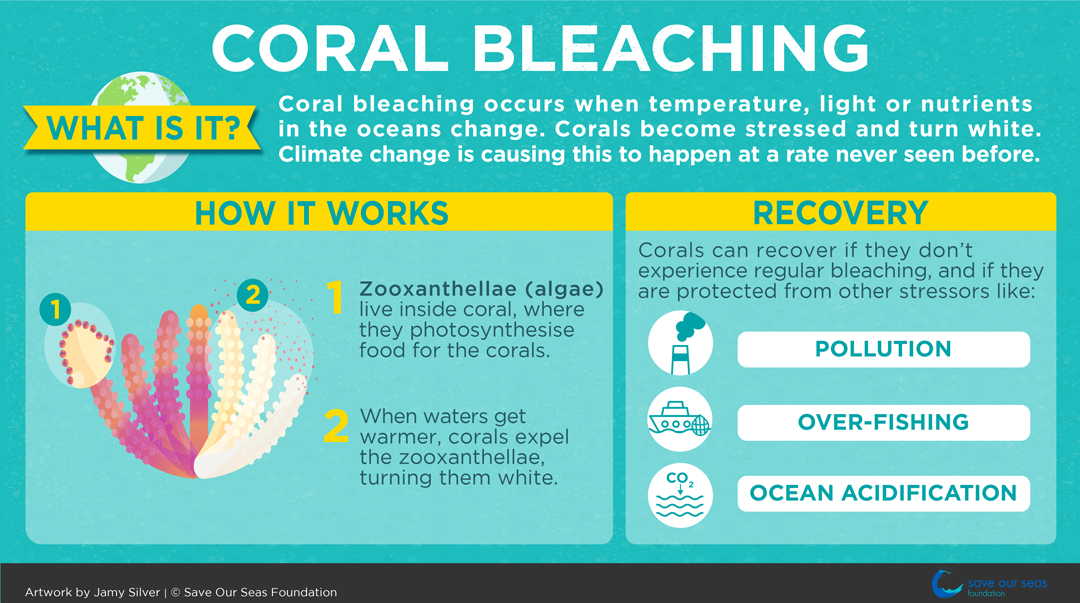

The climate crisis is now recognized as one of the greatest threats to coral reefs worldwide. Increasing ocean temperatures cause coral bleaching – when normally colourful corals turn bright white. This happens because microscopic algae (like miniature plants) live inside corals – in return for a safe place to live, nutrients and carbon dioxide, they provide the corals with food, produced using sunlight. But when corals are stressed – such as when the water around them heats up – they expel the algae living inside them, and the coral’s white skeleton is revealed. If a coral goes for too long without algae, it will die.

Artwork by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

CORDIO – encouraging collaboration for better coral conservation

CORDIO (Coastal Oceans Research and Development in the Indian Ocean), an NGO based in Kenya, focuses on research and conservation of coral reefs in the western Indian Ocean (WIO). One of its core products is the WIO Coral Bleaching Alert and Reporting System. CORDIO combines data (from satellite imagery) on how much heat has been generated in the ocean, with an understanding of how different parts of the WIO heat up, to predict the likelihood of coral bleaching during the hottest months. The team then issues a bi-monthly alert by email, highlighting the probability of bleaching and encouraging network members to monitor their local reefs and share their data. CORDIO currently receives all kinds of data from simple estimates of the percentage of a reef which has bleached, through to detailed, scientific survey data, submitted not just by university students and researchers, but also by park rangers, dive operators, tourists and concerned locals. This assimilation of information from across the whole WIO is invaluable because it shifts the focus from single reefs to a big-picture understanding of the whole region.

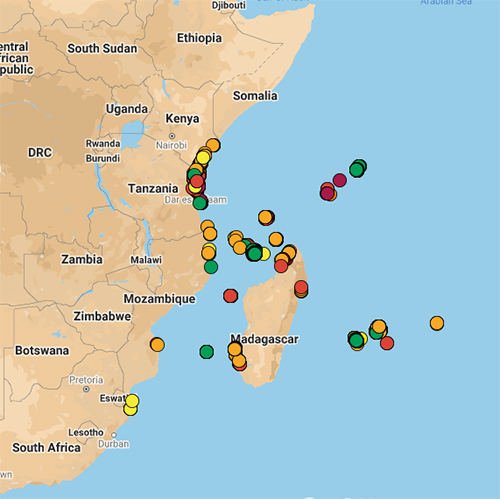

Map showing all the bleaching observations submitted to CORDIO between 2016 and 2020. Dot colour represents the severity of bleaching: Purple - extreme (over 90% of corals bleached), red - high (50 – 90% bleached), orange - medium (10 – 50%), yellow - low (1 – 10%) and none (green). Image © CORDIO.

The high ocean temperatures early in 2020 suggested that bleaching might be widespread in the WIO, and many teams began preparing for an intensive monitoring season.

Collecting data on bleached corals

Blue Ventures has been recording coral bleaching since 2010, as part of their regular coral monitoring surveys in southwest Madagascar, and submit the data they collect to CORDIO. Both local community members and visiting volunteers are involved in scuba diving surveys to investigate reef health and biodiversity, and the extent and longer-term persistence of any bleaching. This year, because of COVID-19, only 12 bleaching surveys were completed, in January and February, before all their volunteers had to leave and survey activities were stopped. “This meant that unfortunately, we could not fully assess whether bleaching occurred in later months”, Abigail Leadbeater, Blue Ventures’ Monitoring and Evaluation Coordinator explained. Bleaching events seem to be happening more frequently around Madagascar in recent years, Abigail noted. “We have been fortunate so far – our reefs have recovered well, even after the serious bleaching event in 2016. But it’s worrying that these events may be occurring with increasing frequency, leaving less time in between for reefs to recover”.

Reef monitoring in the Velondriake, southwest Madagascar. Photo © Hannah Gilchrist | Blue Ventures

2020: What happened?

The Bleaching Alert and Reporting System received bleaching reports from over 22 individuals and organisations in 8 countries during the 2020 season. “In the end, the data we received suggest that the extent of coral bleaching along East Africa’s coastline was less dramatic than we anticipated and certainly less severe than in 2016. That was a huge relief”, said Mishal Gudka, CORDIO’s Programme Manager for Corals. However, whilst the region may have escaped widescale bleaching this year, Mishal cautions that as land and sea temperatures continue to rise due to global heating, it is more important than ever to monitor the WIO’s reefs and collect information both on where bleaching is and is not occurring. CORDIO’s bleaching observation dashboard for 2020 highlights that in some parts of the WIO region, little or no monitoring is being done – in much of Mozambique, for example, and parts of Madagascar – so they hope to encourage new groups to collect data in these areas, to really uncover and understand the full extent of coral bleaching across the WIO.

David Obura, CORDIO founding director, collecting data on bleached coral during a snorkelling survey. Photo © Keith Ellenbogen.

Why should we care about coral bleaching?

Monitoring coral bleaching is important because it enables scientists to develop more accurate predictions of where and when bleaching will occur in the future. “This kind of information helps governments and conservationists plan for coral reef conservation, by identifying resilient coral reefs that should be protected, and by highlighting which regions may be more vulnerable to bleaching”, Mishal notes. “People sometimes feel helpless because bleaching is not a process that can be stopped, once it has started”, he adds. But through the Bleaching Alert and Reporting System, people throughout the WIO have been empowered to make a difference by collecting and sharing information on bleaching, so that in the future it can be used to protect these critical habitats, the many marine species and human communities who rely upon them.

The Maldives, May 2016. Photo © The Ocean Agency | XL Caitlin Seaview Survey.