Endangered Species Day 17 May 2019

Today reminds us which species need immediate conservation focus and is a chance to learn what we can each do to turn the tide for highly threatened biodiversity. Endangered Species Day follows the recent release of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report, which details that an alarming 33% of reef-forming corals, sharks and their relatives (rays, skates and chimaeras), and more than 33% of marine mammals are threatened with extinction.

In fact, in the latest assessment of sharks and rays by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Shark Specialist Group updated in March this year, six of the 58 species that were up for re-assessment were classified as Critically Endangered. Eleven of those species assessed made it onto the updated Red List as Endangered or Vulnerable, making a total of 17 species threatened with extinction in this latest review.

We’ve highlighted a few of the Endangered species and taxonomic groups currently researched by SOSF funded project leaders. Their population trends are disturbing, but amidst all the bad news, it’s worth pausing to pay attention to these interesting ocean creatures and learn a little bit more about what makes them worth protecting.

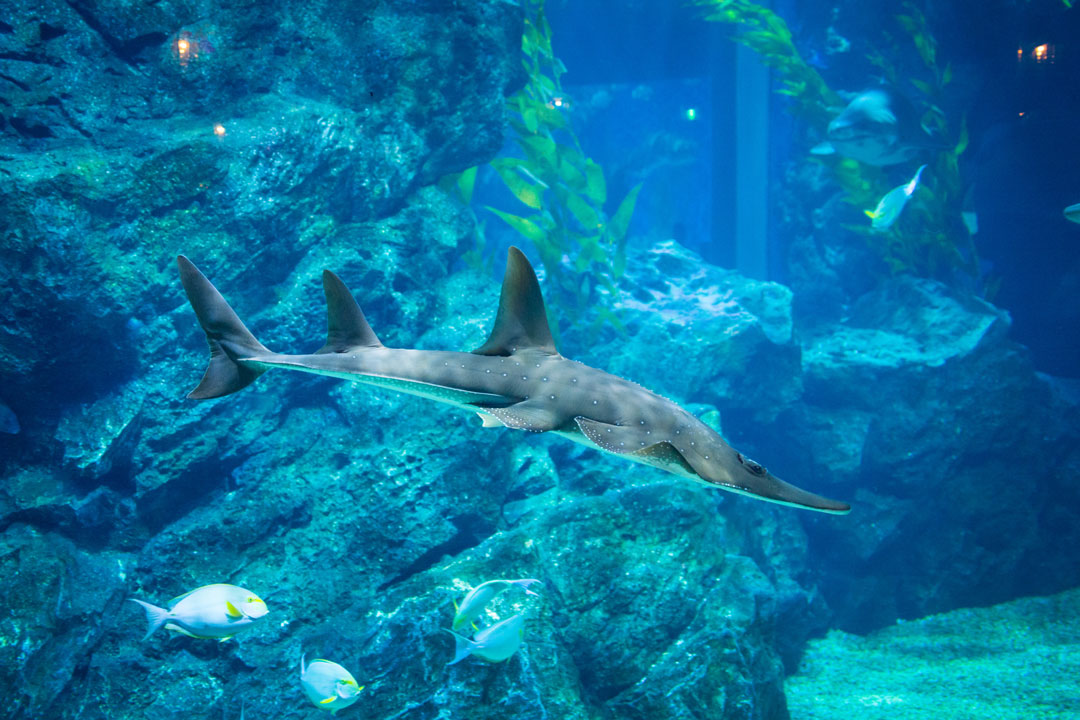

Spotted guitarfish swimming in an aquarium. Photo © Nattanon Tavonthammarit | Shutterstock

Guitarfishes and wedgefishes

Overlooked, under-researched and with much left to learn about them, the species in the families Rhinidae (wedgefishes), Glaucostegidae (giant guitarfishes) and Rhinobatidae (guitarfishes) might look outwardly like sharks but are considered rays. Their high-rise fins gliding above the seafloor, bodies flattened and suited to their surroundings, many species remain equally low on our awareness radars. There is keen urgency to focus conservation action and research on the shark-like rays, and the most recent assessments place giant guitarfishes and wedgefishes in even greater peril than their close relatives, the sawfishes. Often misidentified, highly sought-after for their prized fins and overlapping with coastal fisheries in the shallow seas that are often their primary habitat, scientists are looking to a combination of much-needed approaches to ramp up action for these species.

A green sawfish swimming in an aquarium. Photo © ShaunWilkinson | Shutterstock

Sawfishes

With three species listed as Critically Endangered and the populations of all five sawfishes predicted to be decreasing, these are more than curious creatures with an incongruous-looking rostrum (the nose-like extension that inspires their name). Sawfishes have disappeared from much of their historical range, but where they have been protected in Florida (USA) and northern Australia, there are hopeful signs that their populations can stabilise with the right intervention. In many traditional cultures, sawfishes have reigned supreme as symbols of significance, handed down in stories over generations. Today, trade in sawfish parts is banned under the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix I, but their valuable fins and rostra make them a likely candidate for illegal trade. These species from the Pristidae family have brought together experts from around the world to coordinate efforts to research, monitor and manage their populations, and legislate for their protection.

A juvenile angel shark. Photo © LuisMiguelEstevez | Shutterstock

Angel sharks

Secreted in the sand on the seafloor, their pectoral fins spread like “wings” alongside their camouflaged bodies, several species of angel sharks are Critically Endangered. For the angelshark (Squatina squatina), smoothback angelshark (Squatina angulata), hidden angelshark (Squatina occulta), Argentine angelshark (Squatina argentina) and sawback angelshark (Squatina aculeata), lost habitat as a result of coastal development, and overfishing where they may be caught both as target and bycatch species, need to be addressed to stabilise their dwindling numbers. Several other angel shark species make the IUCN Red List as Endangered, and yet others are considered Data Deficient – perhaps one of the most troubling categories because our insufficient knowledge of these species’ life histories and threats means that they can be left out of conservation planning and management programmes.

A great hammerhead shark pictured in the Bahamas. Photo © HakBak | Shutterstock

Hammerhead sharks

The animal that children watching Finding Nemo grew to know as Anchor, the unwieldy-looking shark with its perpetual sideways glance, cruises our oceans in reality as two species of hammerhead shark that are listed as Endangered: the scalloped (Sphyrna lewini) and great (Sphyrna mokarran). What makes understanding and protecting these species so tricky is that both tend to be great travellers across our seas; the great hammerhead is found in tropical waters across much of the world, and the scalloped hammerhead is additionally noted in coastal, temperate waters. Species such as these point to the need for collaboration and cross-border communication when it comes to improving their management plans and monitoring across their wide ranges. Detailing and enforcing fishing regulations might go a long way to bringing these charismatic ocean nomads off the Endangered list.

A giant devil ray. Photo © Vladmir Wrangel | Shutterstock

Devil rays

Winging its way through the Mediterranean Sea, the giant devil ray (Mobular mobular) has been lost from its former range in the Black Sea. When it comes to confirming reports of its occurrence in other areas, the devil it seems is in the detail (and the data, and DNA) of this species. What makes it different from the spinetail devil ray (Mobular japanica) isn’t yet defined, and more work is needed on clarifying the genetic (and morphological) distinction between species lines. Slow-growing and slow to reproduce, fishing pressure needs to be eased off threatened devil rays that are prized for their gill plates. In the case of the giant devil ray, more effective management of its depletion as a bycatch species is one recommendation to keep this ocean giant charting its course off our coastlines.

A white shark swimming in the Pacific ocean. Photo © Willyam Bradberry | Shutterstock

White sharks

Unlike most of the other species that made it onto our list today, the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is perhaps one of the ocean’s best-known and most recognised inhabitants. Whatever gains this shark has over other elasmobranchs in terms of focus and attention, it more than makes up for in what that infamy has meant for its place in popular culture and its current conservation status. Listed as Vulnerable globally, but Critically Endangered in Europe and the Mediterranean Sea, white sharks remain vulnerable to fishing pressure and the degradation of critical habitats that may, in fact, be important as nurseries or feeding sites. A surprising amount is still unknown about a species that has been splashed across cinema screens for well over 40 years: significant work remains to undo the misinformation peppered across our collective imaginations, and pave the way for scientifically-sound, evidence-based management of their populations.