Endangered species day

Every year in May, our planet participates in Endangered Species Day by sharing the importance of wildlife conservation, as well as highlighting the many threats faced by critically endangered wildlife. Created to keep us aware of how fragile the existence of some animals really is, every Endangered Species Day is important… but this year it seems especially so, as we continue to experience a rapid loss of plants and animals.

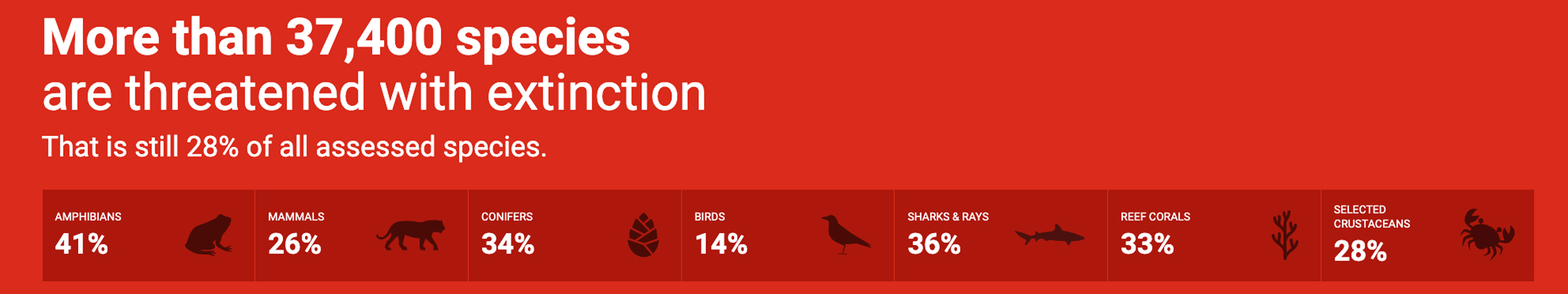

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is the world’s largest and oldest global environmental network, tasked with gathering information on biodiversity and publishing the latest data on the conservation status of thousands of animals under different categories. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, more than 37,400 species are threatened with extinction. In 2014, 25% of all shark and ray species were assessed as threatened, with 25 species critically endangered. A new IUCN Red List assessment on sharks has shown that number is now 35%, with the number of critically endangered assessments tripling (from 25 to 76). This takes the total of all sharks and rays categorized as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered to 355 (76 are critically endangered, 112 are endangered, and 167 are vulnerable); one of the reasons for this spike is a change in the way the assessments have been made since 2014.

The IUCN Global Shark Trends Project is finishing their assessment of all sharks. In the meantime, let’s introduce you to some of the most endangered shark species in our oceans today:

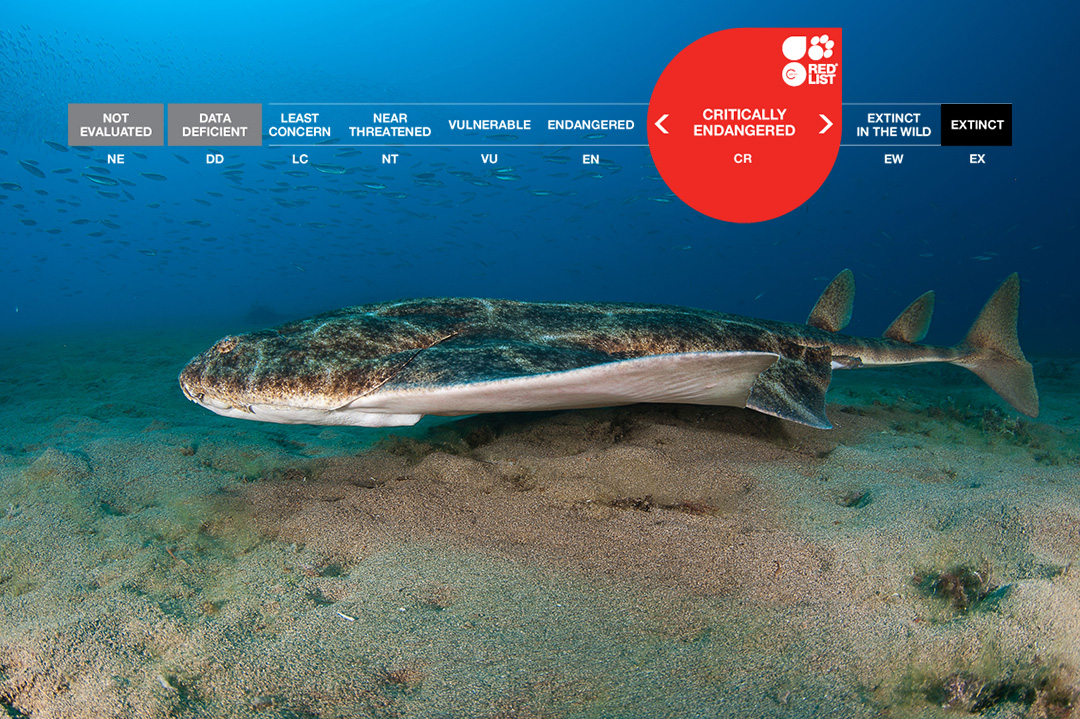

Photo © Carlos Saurez

- Angelshark (Squatina squatina)

The angel shark family (Squatinidae) has been declared the second most threatened [j4] of all sharks and ray families. This medium-sized benthic coastal shark is endemic (native and restricted to a certain place) to the north-east and eastern central Atlantic, Mediterranean and adjacent seas. Camouflaging in the sand or mud, these ambush predators eat bony fishes, cephalopods, skates, crustaceans and molluscs. Due to intense fishing pressure, angelshark populations have had steep declines and local extinctions in much of their range. - Pondicherry shark (Carcharhinus hemiodon)

The little scientists know about this shark that belongs to the Carcharhinidae family comes from the specimens collected in fish markets across the Indo-Pacific region. On the verge of extinction due to large, unregulated fisheries in this supposed range, little is known about their biology or even behavior!

- Sawback angelshark (Squatina aculeata)

It gets its name from the spines present down their back when they fully mature, and once common in the eastern Atlantic and within the Mediterranean Sea. Experts know little about its biology, but know they are extremely vulnerable to being caught in bottom trawling fishing gear. Another camouflaged ambush predator, they are known to eat small sharks, bony fishes, cuttlefish and crustaceans.

- Ganges shark (Glyphis gangeticus)

Often confused with bull sharks, this species is so rare that after its first sighting in 2006, it wasn’t seen again until it re-emerged at a local Mumbai fish market in 2016. Found primarily in Indo-west Pacific rivers and estuaries, most of the observations of this animal come from an area that is facing heavy fishing and coastal development pressure. Part of the Carcharhinidae family of sharks, their biology is largely unknown. - New Guinea river shark (Glyphis garricki)

Found in Papua New Guinea to Northern Australia rivers, estuaries, and seas this shark is often confused with bull sharks due to both of them being grey-white in color. It is known to feed on fishes, other sharks, invertebrates, marine mammals and marine reptiles. Also known as the Northern River Shark, they are taken as bycatch in commercial and recreational fisheries.

- Happy Chappie or Natal shyshark (Haploblepharus kistnasamyi)

Also known as ‘Happy Chappie’, this shark is just one of the many poorly known species of South African catsharks. Described in 2006, what scientists know about this animal comes from three adult specimens that seem to be endemic to KwaZulu-Natal shallow coastal waters. Because of this, any threats they face will have a huge impact to their small population size. - Daggernose shark (Isogomphodon oxyrhynchus)

Endemic to the northern of South America, this shark loves the shallow and highly turbid waters derived from the drainage of numerous large rivers in the Amazonian Estuary. Named after its long and prominent snout, the main threat these animals face is unregulated artisanal fisheries operating throughout their extremely small range. In 2017, NOAA Fisheries listed the species as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

- Sharpfin houndshark (Triakis acutipinna)

Another extremely rare shark, virtually nothing is known about this elusive species! Found off the coast of Ecuador (the Manabí province), scientists have studied few specimens and believe the population of the sharpfin houndshark is very small (<2,500 individuals). Occurring at depths of 50–200 m, like many other species on this list, their population faces increasing fishery pressure.

- Winghead shark (Eusphyra blochii)

This species of hammerhead shark is known for their unique cephalofoil hammer-shaped head which can be almost as wide as half its body length. Found in the Indo-West Pacific from the Arabian/Persian Gulf through to south Asia and northern Australia, they are heavily exploited across their range by overfishing that happens in the continental and island shelves they frequent. Like others in their genus, the peculiar head shape makes them vulnerable to accidental entanglement in fishing nets, such as gillnets and trawls.

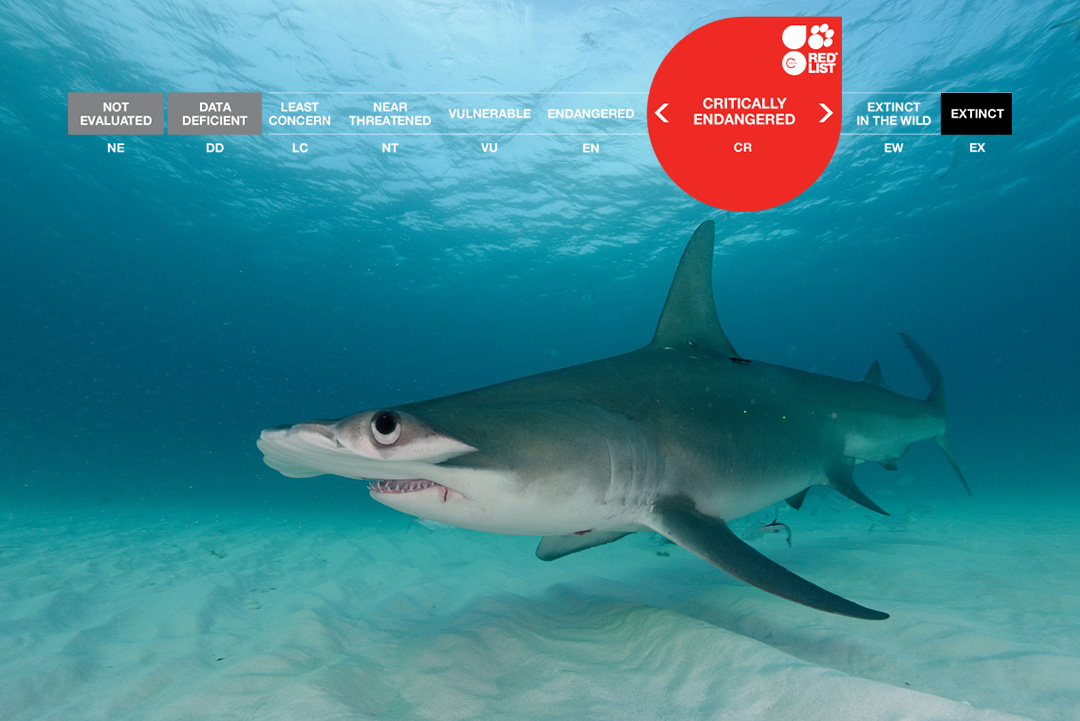

- Great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran)

The great hammerhead is the largest of the 10 species of hammerhead sharks in the genus Sphyrna. Widely distributed throughout tropical and warm temperate waters, they are a coastal species that is often observed over continental shelves. Known to migrates to the equator in cooler months, this solitary predator is targeted by recreational sports fishers due to ‘the fight’ they put up and are prized for their large fins and for the shark fin market. Hammerheads are also caught accidentally in longlines, fixed bottom nets and bottom trawls.

Photo by Michael Scholl | © Save Our Seas Foundation

We share our ‘Blue Planet’ with over 1,200 different species of sharks and rays who have been here for more than 400 million years – they are older than trees themselves! They are indispensable to our oceans, helping keep food webs in balance and providing livelihoods through tourism. That is why this Endangered Species Day, many shark scientists will be focusing on the biggest threats these animals face: overfishing and bycatch. The good news? People are doing something about it! Citizens worldwide are downloading sustainable seafood apps to help them make an ocean-friendly choice about the seafood they eat (some global examples are Seafood Watch, SeaChoice, GoodFish, FishPhone, and Australia’s Sustainable Seafood Guide). Governments and fisheries management organizations are also collaborating to enact more sustainable fishery practices to help sharks and rays out – so there is some hope for a better future for these predators!

Here are three easy ways you can celebrate Endangered Species Day 2021 from home:

1. Attend a virtual Endangered Species Day Event: Check out the various online events that are sharing endangered species stories and how we can all help.

2. Learn about biodiversity: Thanks to local libraries and the internet, there are plenty of resources to get people of all ages ready to learn about the animals that call our planet home and celebrate global conservation wins.

3. Share your favorite endangered species: Show your support for these threatened animals with a photo of your favorite one using the hashtag #EndangeredSpeciesDay!