Collision captured: The impact of boat strikes on basking sharks

After serenely feeding at the surface for hours, a seven-metre (23-foot) basking shark suddenly swerves and tumbles dramatically through the water. Seconds later, a boat’s keel is seen, having struck the shark’s back as it sped across Ireland’s newly established National Marine Park (NMP). For what’s thought to be the first time, SOSF Project Leader Dr Alexandra McInturf and colleagues captured on camera using cutting-edge technology that had been deployed just six hours previously.

Basking sharks are natural navigators that migrate up to 10,000 kilometres (6,213 miles) to reach the rich coastal waters of the UK and Ireland in the warmer months. Here, they aggregate to filter-feed on plankton, cruising the currents and ‘basking’ at the surface.

But the behaviour that sustains their life simultaneously subjects them to their biggest predator: humans. Less than the estimated 50-year lifespan of a basking shark has passed since the intense targeting and harpooning of these animals for their liver oil ended in the 1990s, resulting in the species’ current status as globally Endangered. Yet still it faces a threat, and one that is growing worldwide: boat strikes.

Photo © James Lea

Alex explains that Ireland has taken notable steps to safeguard the basking shark. After a campaign driven by a public petition with more than 12,000 signatures, ‘[it became] the first fish to be protected under Ireland’s Wildlife Act in 2022’.

The Blasket Islands, located off County Kerry, form the backdrop to Ireland’s first NMP, a 283-square-kilometre (70,000-acre) sanctuary established in April 2024. It’s here that Alex and her team are on a mission to uncover the mysteries of basking shark foraging behaviour. Their secret to success? An innovative IMU (inertial measurement unit) device – essentially an animal FitBit – that enables the team to gather real-time tracking data through sensors and a towed camera. Affixed to the shark’s back and designed to detach after 12–18 hours, the unit is then located and retrieved, and the team eagerly download the data that reveal a treasure trove of insights.

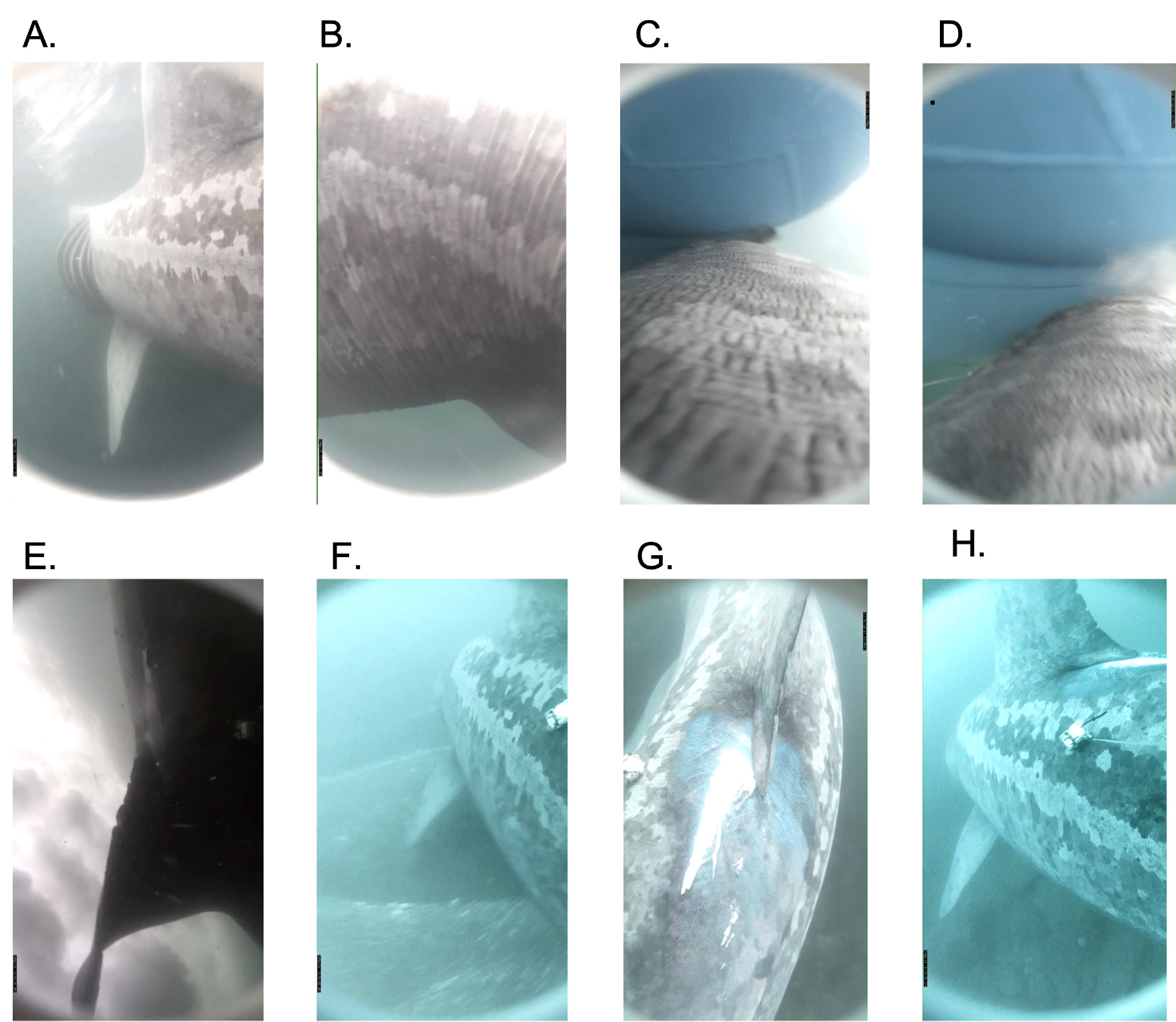

‘Initially, we were skipping through some video when we noticed the tell-tale sign of a boat interaction – blue paint on its back, probably from a ship’s hull. This is not uncommon in the area, but when we jumped back to an earlier clip, the paint was no longer visible. That was when we realised we had probably captured the moment of a ship–shark encounter on camera.’

The shark had been feeding peacefully for the previous six hours when a boat sped into the area. Its keel struck her across the back, just behind the dorsal fin. ‘When we finally saw the ship strike, it was sobering,’ Alex recalls. The camera captured the shark’s frantic response as she was sent spiralling by the force of the collision. ‘I was surprised by how quickly the strike occurred. The shark barely had time to react.’

Still photos taken from the animal-borne camera show the basking shark A) feeding at 413 the surface prior to the boat strike. At 13:53:30, B) the shark attempted to make a large and quick evasive movement. However, C/D) within a second, a large boat keel cut across the back of the 415 shark, just behind the dorsal fin and E) the shark was tumbled through the prop wake. F) The shark immediately increased tailbeat frequency and powered down to the sea floor for 30s. G) Anti-fouling paint (blue), damage to the dermis, and a red abrasion, were evident posterior to the dorsal fin where the keel struck the shark. H) The shark remained associated with the seafloor as it swam in a more directed route into deeper waters for the next 7 hr 27 min without feeding.

The shark’s behaviour changed abruptly. ‘She stopped feeding and immediately dove, expending a lot of energy moving to deeper water offshore. Once there, she appeared to rest on the sea floor for the duration of the deployment.’ Once actively feeding and swimming near the surface – a behaviour critical for her survival – she now stayed close to the ocean floor, motionless at times.

The damage was visible: red abrasions and anti-fouling paint marked her skin. Although there was no severe bleeding or large gash, the physical and behavioural impacts were significant and long-lasting. For the next 7.5 hours, until the IMU released, she did not return to feeding. And these collisions aren’t isolated incidents. ‘During this period, we had only the one tag deployed. What are the odds that the ship strikes the one tagged shark in the area? To me, that suggests that strikes are likely to be more prevalent than we had thought previously,’ Alex warned.

Despite the image of oceans being endless and tranquil, the reality is that they are a labyrinth of bustling shipping routes. Global vessel traffic is on the rise, creating crowded ‘marine roads’ that pose hidden dangers. More than 90% of key whale shark areas overlap with heavy vessel traffic , and an estimated 75% of human-caused deaths of North Atlantic right whales are due to ship collisions .

These incidents often go unnoticed, and not all strikes leave obvious external marks, making it difficult to grasp their true impact. ‘It is extremely challenging to collect in situ data on what happens when animals are struck and how often this occurs,’ Alex explains. ‘This study has offered some insight into the former, and the next step would be to begin to quantify the latter.’

Dr Alexandra McInturf takes a moment to observe a basking shark while out conducting field work. Photo © James Lea

Observing an animal’s behaviour during a strike is rare but crucial for understanding its response and recovery. ‘There is a need to examine further the sub-lethal impacts of our interactions with marine megafauna,’ Alex notes. What are the true long-term consequences of such collisions?

Recognising the need to protect basking sharks is just the start; real change requires concrete actions. With populations here showing promising signs of increase, Ireland’s NMP offers a unique opportunity to establish stronger protection. ‘Conservation momentum for the species in Ireland is growing,’ states Alex, ‘but right now, the only available Code of Conduct (CoC) is a set of voluntary guidelines developed by the Irish Basking Shark Group.’ The team’s findings provide hard evidence that the guidelines must be adopted as enforceable policy.

Continued public support is critical. ‘When on the water, be sure to follow the CoC guidelines,’ advises Alex. ‘It is also extremely helpful when people report sightings because they provide information about species distribution and potential overlap with maritime activities.’ The team is optimistic. By leveraging public support, scientific data and effective management strategies, we can ensure a safer future for basking sharks and make a lasting impact on their conservation.

*Alexandra McInturf, a research associate in the Big Fish Lab at Oregon State University (OSU) and co-coordinator of the Irish Basking Shark Group; Taylor Chapple of the Coastal Oregon Marine Experiment Station (COMES) and Big Fish Lab at OSU; Nicholas Payne of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; David Cade and Jeremy Goldbogen of the Hopkins Marine Station at Stanford University; and Nick Massett of the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group in County Kerry, Ireland.

**Reference:

Behavioral response of megafauna to boat collision measured via animal-borne camera and IMU. Frontiers in Marine Science.

Taylor K. Chapple, David E. Cade, Jeremy Goldbogen, Nick Massett, Nicholas Payne, Alexandra G. McInturf.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1430961/full