Celebrating an ocean stewardship success

The ATAP’s decade of following fish in South Africa’s seas

A marine biologist and fish fanatic, Dr Taryn Murray’s sense of hope is infectious as she enthuses about some of the lessons learnt from the Acoustic Tracking Array Platform’s (ATAP) decade in action. The insights gained from a coast-wide network of researchers working collaboratively to tag and track marine animals have been celebrated in a new paper: ‘A Decade of South Africa’s Acoustic Tracking Array Platform: An Example of a Successful Ocean Stewardship Programme.’ The paper, published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science in May, was authored primarily by Dr Murray, the instrument scientist and manager at ATAP, and Dr Chantel Elston, a current ATAP postdoctoral fellow and an SOSF project leader. Another co-author of the paper is Professor Paul Cowley, who is also an SOSF project leader.

In a sea of disconcerting conservation headlines, this publication highlights how the data collected over the past decade through the ATAP are giving us new insights into ocean animals, their habits and their preferred habitats. The paper also touches on how data-sharing has successfully helped different stakeholders, how their data are used effectively to implement conservation strategies and how communication, outreach and engagement have underpinned the ATAP’s achievements.

Dr Murray and her colleagues have given us a hopeful beacon among dispiriting reports. The information from the ATAP network reminds us of what can be achieved when there is a sense of stewardship underpinning conservation work. ‛We absolutely walk our own talk, there is no denying that,’ she declares emphatically. ‛How are you expected to get buy-in from other stakeholder groups when you aren’t actively participating in stewardship yourself? The key is communication: what we do, how we do it and, most importantly, why we do it and why it is important. That’s the real selling (and turning) point.’

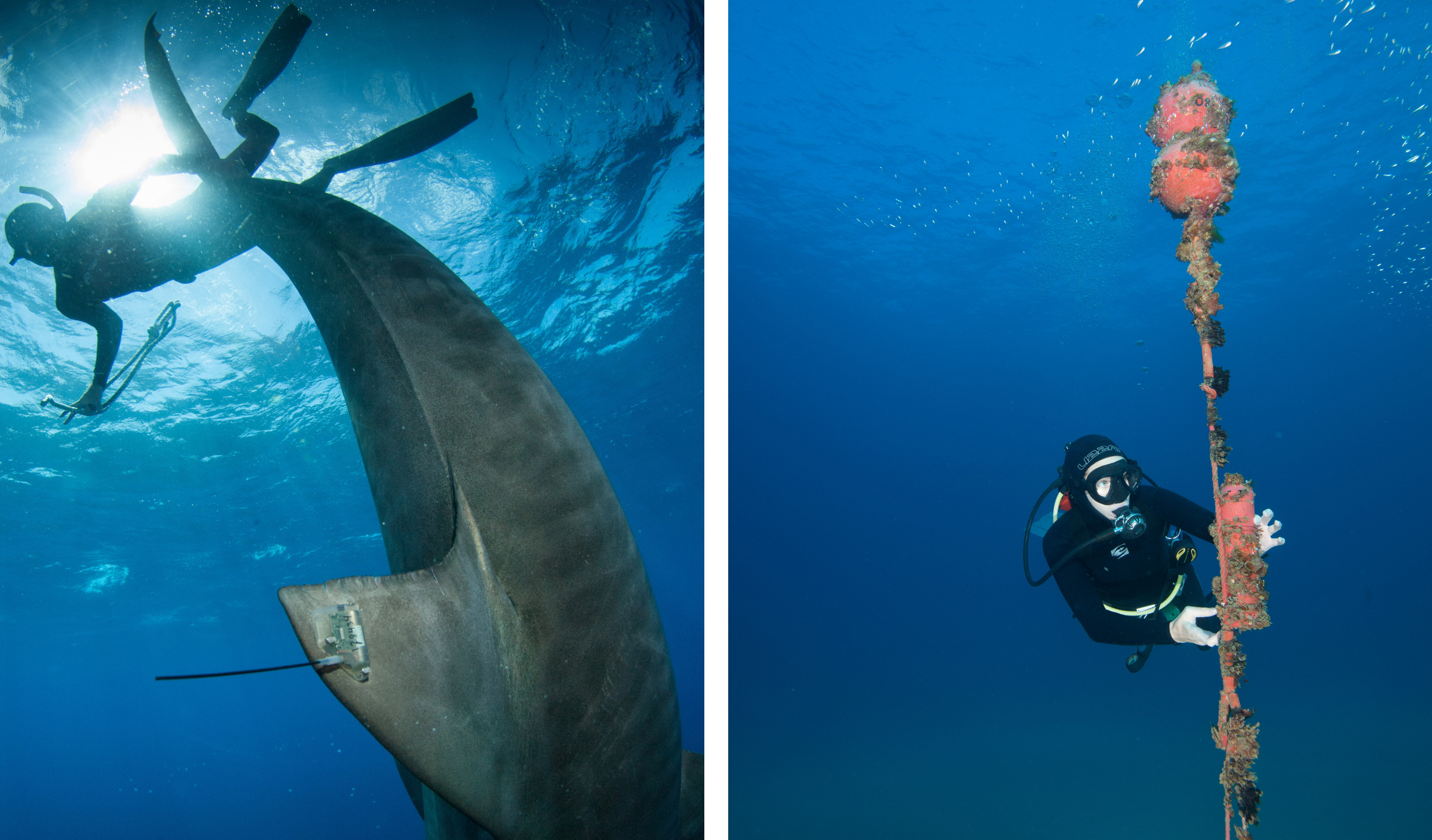

Researcher, Clare Keating checking a receiver mooring. Photo © Ryan Daly

What is the ATAP?

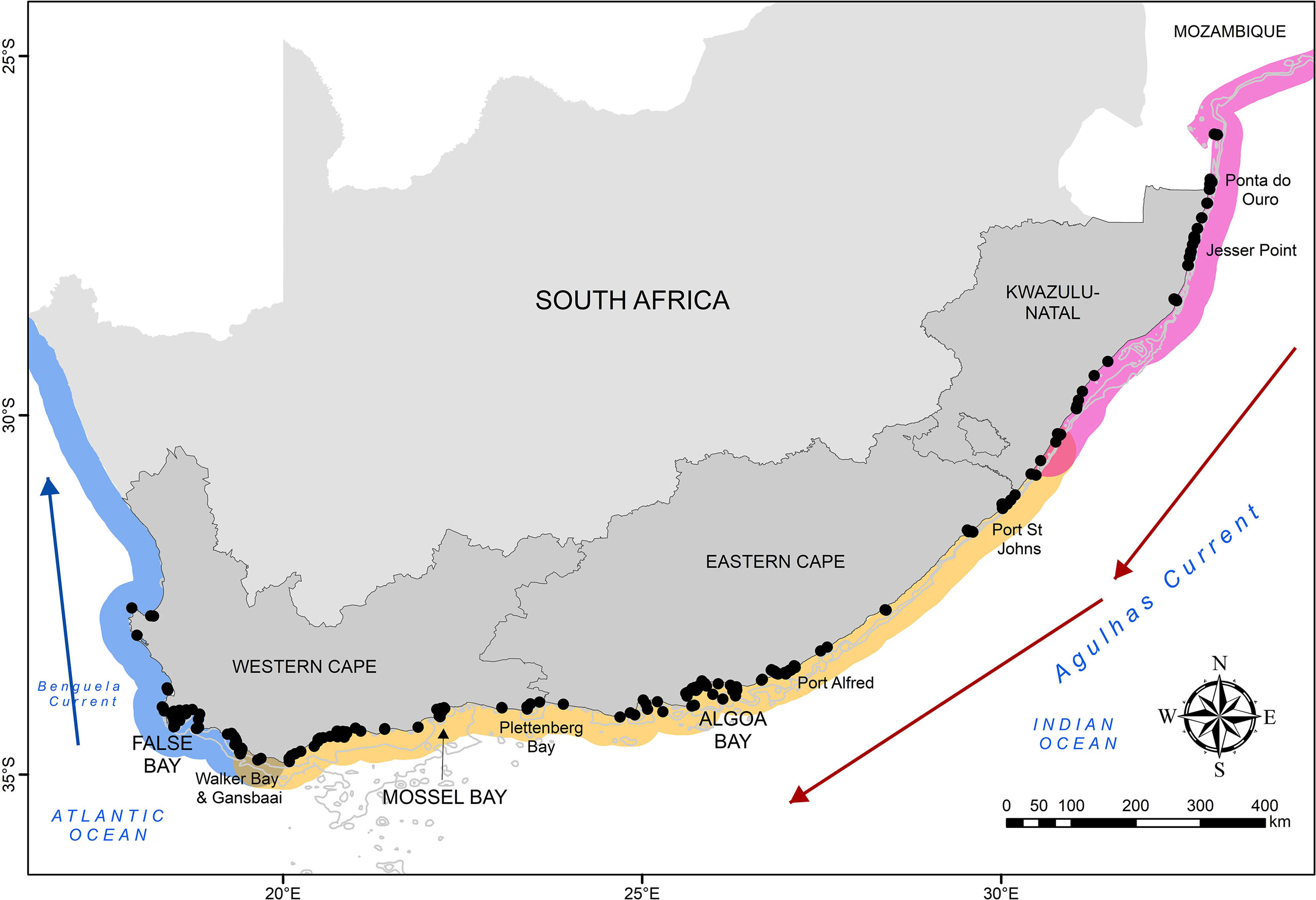

Along 2,200 kilometres (1,367 miles) of the South African coastline, 310 acoustic receivers listen to the life that traverses the contrasting currents at Africa’s southern reaches. These receivers or ‘listening stations’ are placed near the sea floor, where they detect the unique code that ‘pings’ when an animal with an acoustic tag swims nearby. This information is retrieved when the acoustic receivers are removed from the sea and downloaded. Acoustic tracking helps us to understand more about where and how marine animals spend their time in the ocean. ‛Over the past decade we’ve monitored the movements of at least 48 different species, ranging from large predatory sharks and popular angling species to important fishery species, turtles and Critically Endangered rays,’ explains Dr Murray.

Formalised in 2011, in partnership with Canada’s Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) and managed by the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), the ATAP is a coast-wide network of listening stations and temperature loggers that monitors the movement patterns of tagged animals. ‛I guess I stumbled onto this by chance – a case of being in the right place at the right time,’ says Dr Murray. ‛Professor Paul Cowley took me on as a PhD student to assess the movements of juveniles of an estuary-dependent fish species using acoustic telemetry. The ATAP had been formalised six months before I started my PhD and by helping Paul with the data management side of things I very, fortunately, ended up in my current position.’

Dr Murray and her colleagues outline in their new publication how the ATAP, a one-of-a-kind network in Africa, exemplifies the principles of ocean stewardship in action. The information generated by the ATAP plays an important role in the careful management of South Africa’s ocean resources, which in turn are part of a sustainable, equitable future for the country. ‛We are able to address pertinent conservation trends,’ explains Dr Murray. ‛For instance, there is currently a huge drive to conserve wedgefish. Researchers at the Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI) and Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) have tagged 40 whitespotted wedgefish and the resulting data are providing crucial information about their movements, including transfrontier connectivity between South Africa and Mozambique.’

The ATAP receiver locations along the South African coastline. Map © The Acoustic Tracking Array Platform

How does the ATAP work?

The ATAP’s key monitoring sites are three large coastal bays: False Bay, Mossel Bay and Algoa Bay. Acoustic receivers are placed in ‛curtain’ formation, laid out in one or more lines to detect the movements of animals visiting the bays. Most of the rest of the South African coastline is dotted with receivers that can detect animals moving along it. ‛We know quite a lot about the biology – reproduction, age and growth, diet – of many fish species in South Africa,’ says Dr Murray, ‛but often very little about their movements. It is becoming more evident that knowing where and when a species moves is important if we are to protect and manage it more effectively.’

This is the kind of information that the ATAP generates. The data logged on the receivers enable scientists to ask questions about migrations, connectivity between habitats, residency (how long some species stay in one habitat) and site fidelity (some species have a home range or habitat to which they return). The receivers, or the temperature loggers attached to them, also record ocean temperatures. Temperature affects how animals move and monitoring how it changes helps to assess its influence on tagged animals that are ectothermic (their body temperature is influenced by that of their surrounding environment).

‛We were extremely fortunate to have entered the telemetry game when we did. Not only has the number of studies making use of telemetry to assess the movements of multiple species worldwide exploded over the past two decades, but telemetry is now the accepted and most popular method of studying animal movements.’

But the ATAP is not only a network of acoustic receivers; its success relies on a community of researchers who tag and track, collate, share and analyse data, then publish their results and offer conservation and fisheries management advice based on those results. ‛As for data-sharing, we couldn’t ask for a better community of telemetry researchers,’ Dr Murray points out. ‛Almost all the organisations and researchers are, and have been, willing to share their data with the ATAP. We maintain a national database in which all data are stored and researchers have complete access to it through a request system.’

An acoustic receiver in the Mtentu Estuary. Photo © Ryan Daly

What does the ATAP contribute?

The sustainable development of Africa’s coastal communities (by means of well-managed fisheries, for instance) is one goal at the heart of the ATAP’s vision to deliver information that can guide improved fisheries and conservation management. The data on which fish are moving where – and when, and even why – are what ensure that conservation strategies are best placed to deliver the most effective protection or resource management. ‛The beauty of telemetry and the subsequent technological advances means that fish can now be monitored for up to 10 years,’ explains Dr Murray. ‛However, you don’t have to wait 10 years before you see the data – they are collected roughly every six months, so you are able to get an idea of what a species is doing as time passes. In this way “results” are available relatively soon, but obviously the longer the wait, the larger the dataset and the more you’re able to get out of the data.’

A decade of monitoring has delivered information about 1,579 tagged individual animals. Chondrichthyans (sharks, rays, and their kin) represent most of this effort, with 924 tagged individuals across 32 species. All these data are uncovering incredible insights into how sharks live their lives. ‛South Africa has the largest receiver network (in terms of coastal coverage) in Africa, but there are smaller networks elsewhere, including Réunion and Madagascar,’ explains Dr Murray. ‛Luckily, down in the global south, we generally all use the same brand of telemetry equipment (Innovasea, Halifax, Canada). This allows all the deployed receivers to “listen out” for any tagged animal.

Left: Ryan Daly releases a tagged tiger shark. Photo © Steve Benjamin. Right: Researcher, Clare Keating checking on an acoustic receiver. Photo © Ryan Daly

‛Through open communication with researchers in Réunion and Madagascar, together we’ve recorded at least two noteworthy movements. The first was a bull shark tagged in southern Mozambique that swam across the Mozambique Channel and was detected at Nosy Be in Madagascar. Secondly, a tiger shark tagged in Réunion was recorded moving to Port St Johns on South Africa’s Wild Coast. It then turned around and swam back to Madagascar, where it was unfortunately caught. Both these species are known to undertake large-scale movements and migrations, so although interesting, these movements are probably not that unexpected. More surprising is the sheer scale of movements some species make, such as the annual coastal migrations of bull sharks and bronze whalers or the complete residency shown by species such as the flapnose houndshark.’

These kinds of results are critical for guiding conservation strategies. One such strategy is the expansion of existing marine protected areas and the delineation of new ones to protect vulnerable species and their critical habitats, or sensitive ecosystems. Here, the longevity of the ATAP programme is bearing fruitful results. ‛The ATAP is already contributing data that have been incorporated into the development of a systematic conservation plan for elasmobranchs (sharks and rays) in South Africa, a process driven by WILDOCEANS, a local marine conservation NGO,’ says Dr Murray. The question of whether marine protected areas work to protect sharks has been a tricky one to answer, given that most of them have not been designed with sharks and rays – and their critical habitats – in mind. ‛It is very exciting to see the data used in this way and shows promise moving forward when we have to motivate for improved management regulations and conservation measures based on how animals move.’

On a global scale, the Important Shark and Ray Areas (ISRAs) process aims to put sharks on the marine protected areas map and at the top of the agenda to expand these areas. Thanks to programmes like the ATAP, South Africa is well placed to identify critical habitats for sharks and rays and motivate for their inclusion in an expanded marine protected area network. ‛The beauty of our current network is that we can identify important movement corridors or areas simply by looking at the number of animals (and species) detected and how often they are detected. We would absolutely love to contribute data towards the ISRA process,’ concludes Dr Murray.

Tiger shark movement data have shown some of the amazing distances travelled by this species. Photo © Ryan Daly.

Where is the ATAP heading?

Our changing climate heralds a changing ocean and the ATAP network will need to strengthen and expand its capacity to measure temperature to help understand how animals are responding to rising sea surface temperatures, increasing marine heat waves and ocean acidification. There are also hopes to expand the listening power of the acoustic receiver network into neighbouring Namibia in the west, and further north in Mozambique and up the African east coast, where good relationships exist but require capacity and implementation.

Tagging a tiger shark. Photo © Steve Benjamin

What can we learn from the ATAP’s decade of tracking?

Nothing to do with the sea comes without challenges and setbacks. ‛The majority of the challenges have related to the equipment. In the early days, we experienced a spate of equipment losses and had to keep tweaking our mooring system until the losses decreased and we were happy. Though the loss of equipment isn’t as bad as the loss of data! Running expenses are also a constant challenge. However, through long-term partnerships with organisations such as the Save Our Seas Foundation we are able to maintain the platform.’

Above all, central to the message from the publication is hope. Africa, the authors write, is a place of opportunity rather than failure. When we understand and apply the principles of stewardship, we can work effectively to understand the continent’s blue resources and implement measures to conserve those resources to the benefit of its people in the future. This kind of stewardship relies on cooperation, communication and commitment. With a decade of connecting collaborators and innovating to generate information now under its belt, the research community that makes up the ATAP network has undoubtedly shown that it is capable and committed.