ATAP in the Indian Ocean: An interview with Paul Cowley

What is ATAP?

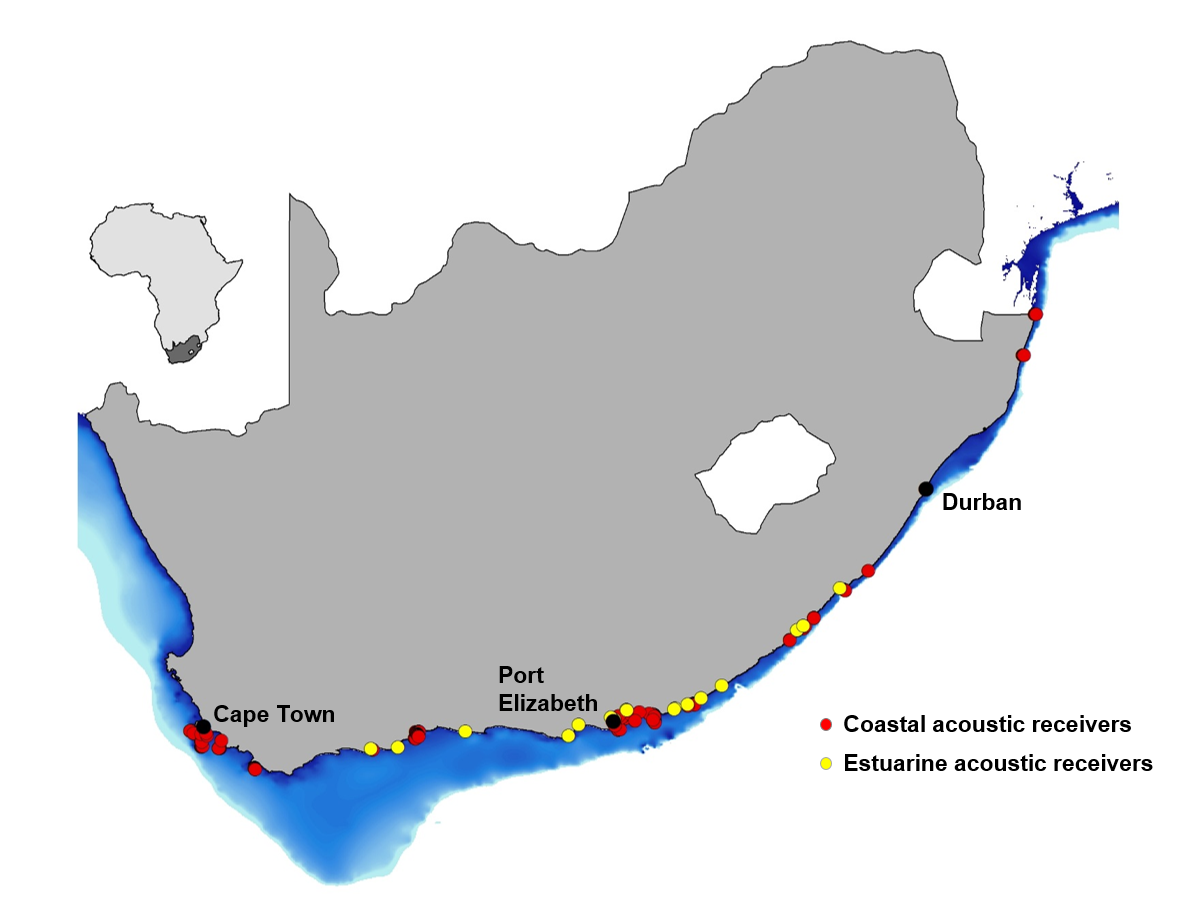

The acronym ATAP stands for Acoustic Tracking Array Platform, which consists of a network of listening stations deployed in coastal waters around the southern African coastline. The deployment of these automated data-logging receivers starts at Hout Bay in the Atlantic Ocean and stretches eastwards all the way to the southern coast of Mozambique in the Western Indian Ocean.

I think probably the best way to explain how the array works is to compare it to a cellphone network. Besides having the liberty to make phone calls wherever we are, every time we go past a cellphone tower, the network knows our whereabouts. A cell phone company therefore has the ability to track us by the cellphone towers we have been past. Similarly, we tag fish with uniquely coded transmitters that go past our receivers which function like cellphone towers, and indicate to us where tagged fish have been. The receivers will log and store a date and time stamp of when any of the tagged fish were in the vicinity of a receiver. Sometimes a tagged fish might pass our monitoring towers without being detected which is a bit of a pity, but we have several of these listening lines that run perpendicular to the shore, along our coastline and we are collecting some amazing data. Certainly for some of the species, we can start putting the pieces of the puzzle together to help us understand more about the mysterious underwater lives of these creatures.

Map of ATAP off the coast of southern Africa

Why is ATAP useful for biologists and conservationists?

The ATAP provides us with valuable information on the movements and migrations of marine animals. Such information is crucial for informed decision making to assist with the management of over-exploited fishery species. The information can also shed light on the use of “hots spots” that can be included into spatial planning initiatives, such as marine protected areas. Furthermore, information on multiple year migrations together with temperature data can shed light on potential climate change effects. Many of our tags are on sharks. There are now nearly 50 white sharks and 20 sevengill cowsharks tagged with transmitters that have a 10 year lifespan! Multiple year data on these individuals will allow researchers to answer questions about what patterns can be attributed to oceanographic conditions or climatic conditions and determine whether all individuals undertake similar migrations every year. It is also encouraging to see that more and more species are getting tagged and that more researchers are using this marine research platform.

I recently got a call from the research team working on the Brede River Estuary to say that they detected a bull shark that was tagged at Port St Johns. The same individual has also been recorded on receivers at the Mbashe Estuary, Coega harbour, Port Elizabeth harbour and on our offshore receivers near Port Alfred, Port Elizabeth (Algoa Bay) and Mossel Bay. There are at least another 20 tagged bull sharks in the array and with time I am confident that with similar information from other individuals we will better understand their movement patterns and use of estuaries around our coastline.

Bull shark ready to be tagged. Photo Ryan Daly

How many animals have been tagged and how many receivers have you got off the southern African coast?

In South African waters at the moment we have about 350 active tags. We want to increase that number because we have a lot of investment in terms of receivers in the water. We currently have 171 receivers in the water and we want them to work harder, so we are really encouraging researchers to tag more fish. Considering that ATAP provides an unprecedented opportunity to study animal migrations, we are confident that through broader collaboration researchers will have improved chances of being successful with grant applications to purchase extra transmitters to compliment the studies that are currently going on.

Which species have you targeted so far?

Starting in the Western Cape, various research teams have tagged white sharks, seven gill sharks, white steenbras, bull sharks, spotted grunter, dusky kob and leervis. In the past there were also smaller dedicated studies on reef fish like red roman. We even did some short-term studies on cat sharks, but the batteries on those transmitters have expired now.

ATAP also collects data on 35 raggedtooth sharks, some tiger sharks, and we also have one or two odd individuals like a thresher shark that was tagged off Port St Johns.

Further up the East Coast, a new project on potato bass and green jobfish has just commenced. At the moment we have about 15 species with active tags.

How are you going to use the data?

Firstly, the data collected by ATAP belongs to the researcher(s) that tagged the detected animal. It is hoped that the data will be used to address the conservation needs of threatened and/or vulnerable species. For example, some of the estuarine associated fishery species have been very well studied and there is already very strong evidence to suggest that the importance of estuarine habitats have been ignored in terms of spatial planning initiatives in South Africa. High site fidelity by estuarine-dependent juveniles makes them extremely vulnerable to fishing pressure in their nursery habitats. It is hoped that the information gathered will lead to the establishment of estuarine protected areas that will complement the good network of marine protected areas in South Africa. The challenge is that estuaries are sought-after areas for development and most large systems in this country already habour towns with high population densities. Because people live there, it’s going to be more and more difficult to implement no take zones. Furthermore, it is possible that the data collected on the large predatory sharks will assist with bather safety initiatives and the mitigation of shark attacks.

How does Save Our Seas Foundation support ATAP?

Maintaining a large acoustic receiver network with a long-term vision, like ATAP, is an extremely time-consuming and expensive exercise. SOSF provides much needed funding to service and redeploy the listening stations, which ultimately ensures that ATAP’s infrastructure is maintained to collect the data on all the tagged animals swimming around our coastline.

Diver checking acoustic receiver. Photo by Ryan Daly