Alarm as scientists announce 4th global coral bleaching event

The recent announcement of a major global coral bleaching episode (NOAA confirms 4th global coral bleaching event | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) is a distressing signal of how our rapidly changing climate and consequently warming seas are impacting life in the oceans. This episode marks the fourth global bleaching event in history, and the second in the past 10 years. The southern hemisphere looks set to be hardest hit, with Reef Authority (Australia) confirming on 8 March 2024 that two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef is showing signs of heat-induced coral bleaching.

For decades, coral scientists have warned that rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are warming and acidifying our oceans, putting corals under stress and increasing both the severity and frequency of bleaching events. From the 1998, 2010 and 2014–2017 global bleaching events, scientists concluded that bleaching is the greatest threat to coral reefs worldwide. In 1998, 8% of the world’s coral was killed. The period 2009–2018 saw 14% of the world’s coral die. But there is hope. Bleached corals are vulnerable, but don’t always die if given the time and conditions to recover sufficiently. Scientists have been feverishly monitoring reefs ahead of the 2024 event and are better placed to manage, monitor and salvage these ecosystems. With experts around the world working at the cutting edge of coral conservation and collaborating networks sharing solutions that range from AI-powered monitoring to critical coral nurseries, their commitment to saving the reefs is a hopeful sign. This can – and should – act as a rallying moment to call for stronger climate action.

The USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) announced that the bleaching, which is due to heat stress linked to the cyclical El Niño phenomenon, has been recorded in both the northern and southern hemispheres of each of the major ocean basins (Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans) between February 2023 and April 2024. The impact has been traced to at least 53 countries, territories and local economies, with worrying consequences for the communities that live there. In fact, mass bleaching of coral reefs has been confirmed throughout the tropics since early 2023, with NOAA reporting bleached reefs in Florida (USA); the Caribbean; Brazil; the eastern Tropical Pacific (Mexico, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia); the Great Barrier Reef (Australia); the South Pacific (Fiji, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Samoas and French Polynesia); the Red Sea (including the Gulf of Aqaba); the Persian Gulf; and the Gulf of Aden. The bleaching extends to the Indian Ocean, where reefs in Tanzania, Kenya, Mauritius, Seychelles, Tromelin, Mayotte and off the western coast of Indonesia have all been affected.

The vibrant coral reefs of French Polynesia. Photo © Sebastian Staines

What are corals?

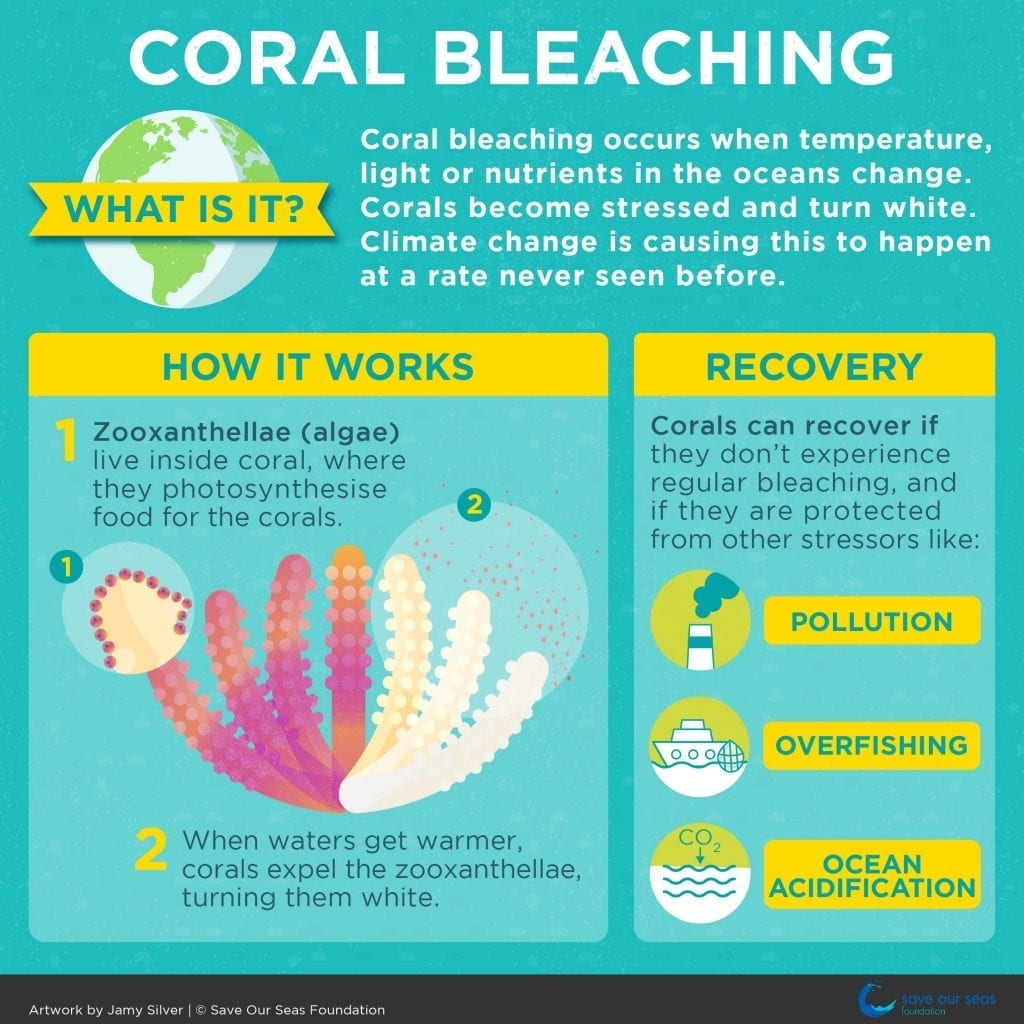

Corals are colonial animals; that is, they are tiny individuals (called polyps) that often form large colonies that live and grow (and depend on each other for survival) connected to one another. These little polyps can use ions in the sea water around them to build their own limestone ‘skeletons’, which form hard coral reefs. (Scientists distinguish between ‘hard coral’ and ‘soft coral’ species, the former usually being the reef-building kind.) Coral polyps are colourless, but are given their distinctive kaleidoscope of Kodachrome colours by symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae that live in their tissues. The zooxanthellae algae use the waste generated by coral polyps to photosynthesise (convert light energy into food) and give off oxygen and carbohydrates that the coral polyps use to feed and grow and help build reefs.

What is coral bleaching?

Corals respond to stress (typically, but not always, heat stress) by expelling the zooxanthellae from their tissues (What is coral bleaching? (noaa.gov)). Without the colour-rich algae, corals appear bleached white (hence ‘coral bleaching’). Bleached corals can recover if given sufficient time and if the surrounding ecosystem is intact (Oceans of hope – Save Our Seas Foundation). In other words, they need to be protected from additional stressors like ocean acidification (which impacts their reef-building abilities), overfishing and pollution. Scientists project that if we remain on the same development trajectory, 90% coral reefs will bleach annually by 2050. The frequency and severity of bleaching events is what will ultimately determine the ability of coral reefs to recover – and whether we can save reefs worldwide.

Why do we need coral reefs?

Coral reefs cover a mere 0.2% of the sea floor, but they pack an outsized life-support punch, hosting at least 25% of the ocean’s species. Coral reefs are found in more than 100 countries and territories, and these critical habitats act as fish nurseries, offer protection against storm surges, nurture livelihoods and fisheries, inspire tourism, underpin culture, safeguard spirituality and secure economies. In fact, coral reefs provide goods and services estimated at US$2.7-trillion each year.

What is being done to save coral reefs?

It’s hard not to become disillusioned by the plight of coral reefs. It’s harder yet to understand how to help. There is, however, much hopeful work being done by dogged scientists and conservationists. In Florida, NOAA is moving coral nurseries to deeper, cooler waters and deploying sunshades to protect corals elsewhere through its Mission: Iconic Reefs programme. The Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) is sharing its Reef Cloud AI technology to help transform coral reef monitoring and provide real-time insights over this tense global period. In the Western Indian Ocean, a region with 220 million people and where the ocean brings in at least US$20.8-billion annually, scientists have warned that coral reefs face total collapse in the next 50 years (Vulnerability to collapse of coral reef ecosystems in the Western Indian Ocean | Nature Sustainability). Here, CORDIO East Africa is working with The Nature Conservancy and Reef Resilience to coordinate a response to the bleaching episode, and posts regular updates and bi-weekly alerts monitoring the unfolding situation on its website (Indian Ocean Coral Bleaching – CORDIOEA).

Some researchers are investigating the thermal tolerance of corals to understand whether some species can shift their distribution (either latitudinally polewards, or into deeper, cooler waters); some are identifying heat-tolerant species of corals that can be selectively bred; and others are figuring out how to raise corals in captivity to repopulate reefs that need to recover after bleaching episodes (Coral Reefs That Can Finally Beat the Heat | WILD HOPE). For instance, Peter Musila and colleagues from A Rocha in Kenya have been monitoring more than 600 tagged corals in 70 plots in Watamu Marine National Park since 2020. Ahead of this 2024 bleaching episode, the team knew to prepare to monitor heat tolerance and use what they learned from the 2020 bleaching event to identify colonies that are suitable candidates for coral gardening and reef restoration efforts that have been approved by Kenya Wildlife Services.

And more researchers are focusing on the ecosystem at large: they investigate the fish that graze corals, the sharks that keep the food web’s structure intact, and the host of complex interactions that make these habitats work. Findings from the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC) indicate that while many hard corals were lost in the 2015–2016 coral bleaching event, some of the sites surveyed showed little mortality of corals of any kind. And deeper reefs, which experience slightly cooler temperatures and are covered in corals that are more resilient to temperature fluctuations, lost less hard coral cover to bleaching. The scientists monitoring coral reefs in this part of Seychelles attribute the recovery of these coral reefs to keeping fish populations stable and well-managed and limiting human disturbance around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll. They have posited that the type of sea-floor cover might be the result of a thriving fish community that grazes the algae on the reefs and few stressors other than rising sea temperatures in this region.

Finally, there is work being done to understand the relationship between coral reefs and people; in particular, vulnerable coastal communities that will be hit hardest by the loss of coral species. In some places, like Kenya, scientists are collaborating with coastal communities to monitor and manage coral reef systems and have created coral reef monitoring guides adapted for citizen scientists.

The acropora coral reefs at D'Arros Island in Seychelles are home to an abundance of marine species. Photo by Dillys Pouponeau | © Save Our Seas Foundation

What can you do?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the United Nations have highlighted how actions are not being implemented fast enough to stave off some catastrophic impacts of climate change. Chief among these is slowing the rate of ocean warming, with sea surface temperatures having reached record levels in Florida in 2023. Change needs to come swiftly and decisively from the top down; that is, governments need to make good on their climate commitments – urgently. There is still merit in all of us making lifestyle changes that benefit our climate: buying local, reducing travel, lowering food waste, ditching fast fashion, eating a largely plant-based diet, cutting out single-use plastic (which is connected to big oil and gas production) and making an energy-efficient home are all beneficial, quite aside from contributing to coral conservation. But holding politicians (and by extension, big business and the fossil fuel industry) to account is paramount. Attend community gatherings, check your finances (make sure your banking and investments are divested from coal and oil), educate others, and vote.

To become involved and educated over the course of this coral bleaching episode, you can check the conditions of the Great Barrier Reef thanks to Reef Snapshot, information published by AIMS, CSIRO and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority from aerial bleaching surveys conducted over the Great Barrier Reef in February and March.

Visit the ICRI coral bleaching hub to stay on top of the latest information (Coral Bleaching Hub | ICRI).

ICRI will be hosting a webinar on Tuesday, 14 May 2024 to present and discuss the status of the 4th Global Bleaching Event and the role of the global coral reef community. You can register your interest in attending at #ForCoral Webinar Series – The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event | ICRI.