2021 Eugenie Clark Award

We are proud to announce Brit Finucci as this year’s recipient of the Eugenie Clark Award, which was given at the end of this year’s American Elasmobranch Society (AES) conference.

The Eugenie Clark Award was created after Eugenie’s passing, to ensure that the legacy of the ‘Shark Lady’ would live on and that future female scientists would continue to contribute towards shark research.

The Eugenie Clark Award on display at Mote Marine Laboratory. Photo © Mote Marine Laboratory

Launched in 2015, by the American Elasmobranch Society with the support of the Save Our Sea Foundation and the Mote Marine Laboratory, the annual $2,500 Eugenie Clark Award is granted to female early-career scientists who are part of the AES and demonstrate perseverance, dedication and innovation in biological research and public outreach for sharks, rays and other elasmobranch fishes – just as Clark did.

Brit Finucci is a fisheries scientist from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) and an upcoming leader in chondrichthyan research. She has an already impressive career in shark and ray conservation and management, and since completing her PhD in 2016 has published 16 peer-reviewed papers, 22 technical reports and two book chapters on deep-sea sharks. Her present research focuses on the management of elasmobranch bycatch in deep-sea fisheries, and she has been involved with nearly 200 IUCN Red List assessments to date. Brit has also co-led a number of international workshops for the IUCN Shark Specialist Group, and has advised on future shark research efforts for the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), West Africa, and the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Brit is also the acting president of the Oceania Chondrichthyan Society.

Q & A with Brit

What inspired you to pursue and career in shark and ray research?

Honestly, when I was younger, I thought I would study dolphins (unfortunately, I have a tattoo to show for it too). I think I made the switch to sharks when I realised how little we know about so many chondrichthyan species. As many of my friends and colleagues already know, I definitely have a soft spot for all the weird deep-water species that have so many fascinating adaptations to such an alien world. I find the added complexity of these charismatic marine megafauna being an important marine resource super interesting, and also a very important and difficult aspect in managing and conserving these species.

Can you tell us a little more about the work that you are currently doing?

My current shark-related work is fairly diverse. Part of my job includes quantifying and monitoring bycatch and discards in New Zealand’s large offshore fisheries, and that includes many of our deep-water sharks. I’m also working on a mark recapture study for the Antarctic skate (Amblyraja georgiana) in the Ross Sea, and we are currently setting up some new age and growth projects for white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias), and for some our harder to age sharks. New Zealand may be a small island nation lost out in the South Pacific, but we have a considerable diversity of chondrichthyans and plenty of work that needs doing! In my spare time, I’ve been setting up the newly established Deepwater Chondrichthyan Working Group for the IUCN Shark Specialist Group.

From a conservation perspective, why is your work important?

There is A LOT of information out there; often research can be quite complex (I don’t understand half of it!), and important findings can become inaccessible or lost behind paywalls, or when it is unpublished or published in languages other than English. Outputs like IUCN Red List assessments are a means of providing a publicly available source that condenses all available information on a species in one place. A lot of work goes into ensuring assessments are accurate and inclusive, and are written in a way that anyone can understand. It’s important because these assessments often drive research, conservation, and management decisions.

What are your hopes for the future for the field of elasmobranch conservation?

We all know many sharks, rays, and even a few chimaeras are in need of conservation action now. It’s great to see so many projects around the world funded by organisations like SOSF, and it’s very encouraging to see research being conducted on a growing diversity of species. I hope to continue to see projects on all chondrichthyans, not just threatened species. There is also a need to understand our data poor sharks, rays, and chimaeras now so we can ensure they don’t end up as a threatened species in the near future.

How has Genie’s career and legacy influenced you?

It really is an honour to receive an award dedicated to Genie. Genie paved her way at a time when women were not expected to have the career she did. Fisheries is still a very male-dominated world and, in all honesty, there are days where I’ve nearly had enough and want to walk away because that ‘old-school’ mentally still lingers. Having stories like Genie’s inspires me to persevere and carve out a better future for all researchers.

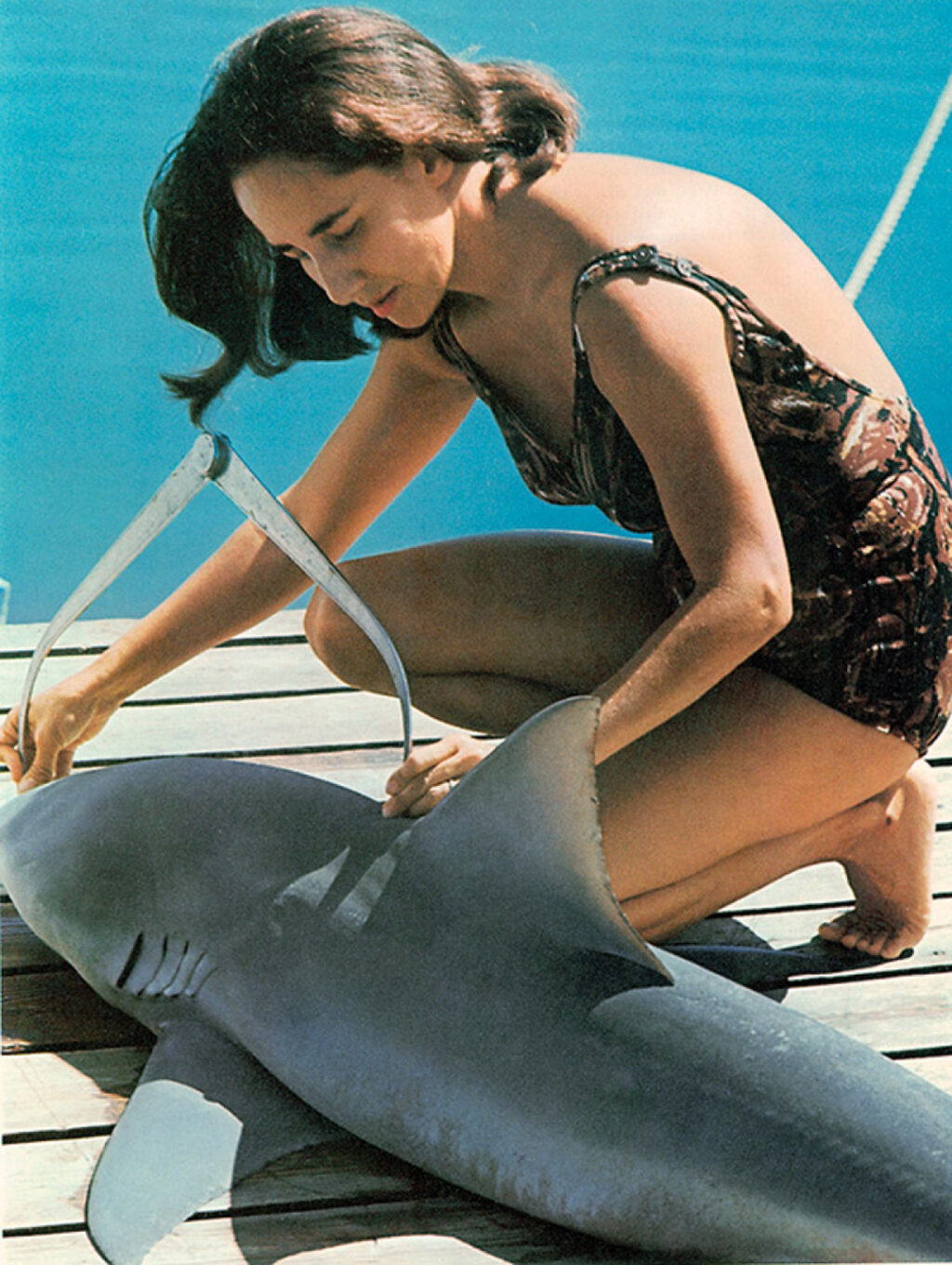

Eugenie Clark taking the measurements of a bull shark. Photo © Mote Marine Laboratory

Dr Eugenie Clark (1922 – 2015) was a pioneer in research on the biology of elasmobranchs (sharks, rays, chimareas), and she was able to forge her career during a time when women were discouraged from becoming research scientists. Clark was instrumental in educating thousands of college students, and she contributed to hundreds of technical publications, as well as many books and articles for popular audiences. She passed away at the age of 92 in 2015.

Clark made her mark in understanding the natural history, reproductive biology and behaviour of sharks and other fishes. The ‘Genie’ Award will honour her, and continue her legacy of inspiring and encouraging excellence among other young women.