Protecting the pristine: SOSF-D’Arros Research Centre

The Save Our Seas Foundation is funded and driven by people who are in awe of our oceans. Many of them have spent years searching for mythical sites of unimaginable marine abundance. In an effort to respect and protect such places, the foundation has become the steward of one such site in the Western Indian Ocean: D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll in the Seychelles.

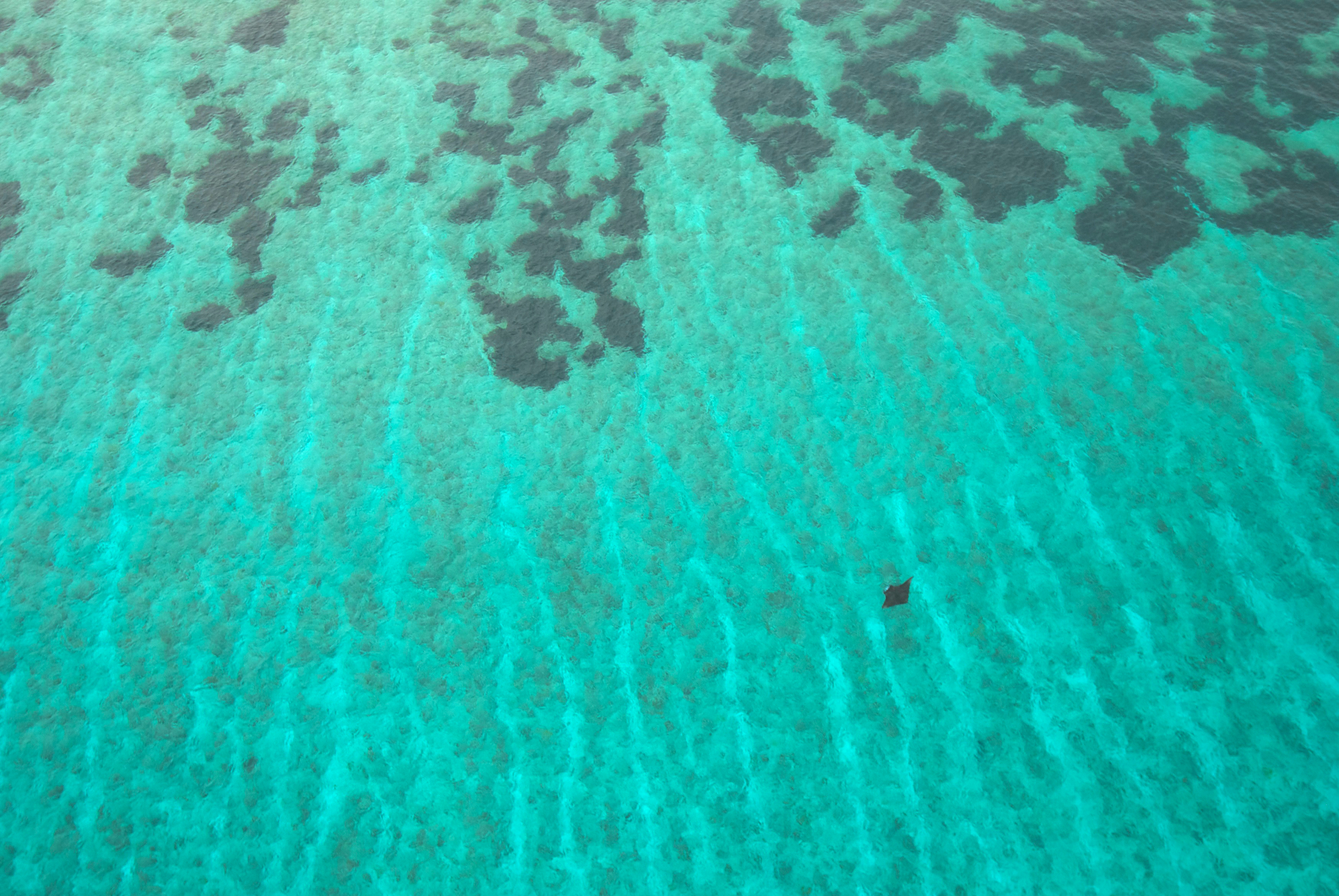

The natural environment of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll is among the most pristine and spectacular in the world. Scores of sharks, manta rays, turtles, stingrays and fish inhabit the lagoon and the surrounding coral reefs while flocks of seabirds roost in trees overlooking tranquil beaches.

The D’Arros Research Centre (DRC) was established in 2004, and tasked with becoming a regional centre of excellence for marine and tropical island conservation. The mission statement of the SOSF-DRC is to preserve and showcase the ecological integrity of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll through research, monitoring, restoration and education.

Over the past 10 years an increasing number of research projects and monitoring programmes have been implemented. More recently the SOSF-DRC expanded its activities to include ecosystem restoration and environmental education. To date the SOSF-DRC has initiated 34 projects in collaboration with more than 25 institutions resulting in two PhD dissertations, one MSc dissertation, nine scientific journal publications and 27 scientific reports.

A manta ray glides over D’Arros reef. These are some of the most beautiful and intelligent fish in the sea. The SOSF-DRC is currently running targeted research into the ecology and movement of manta rays and more than 30 have been fitted with acoustic transmitters.

D’Arros and St Joseph support one of the largest nesting sea turtle populations in Seychelles. Hundreds of endangered green and hawksbill turtles migrate annually from their distant foraging grounds to nest on its pristine beaches. Nesting activity has been monitored on a daily basis since 2004 and, encouragingly, numbers appear to be on the rise. Recently, nesting hawksbill turtles were fitted with satellite tags so that we can learn where they go to forage.

Beaches fringed with coconut palms may be beautiful, but the terrestrial ecosystems at D’Arros and St Joseph have suffered significantly at the hand of man. By the early 1800s native vegetation had been almost entirely replaced with coconut plantations and nearly all mangroves cut down for timber. The DRC currently manages an ambitious forest rehabilitation project in which abandoned coconut plantations are systematically replaced with indigenous forest.

The roseate tern Sterna dougallii was first identified in 1812. Their diet consists mainly of small fish, which are caught by plunge-diving. The bird is extremely widespread and will often migrate between Africa and England.

Petit Four (P-2-4 for non-French speakers) the giant tortoise is a special part of the D’Arros team. He originally came from Aldabra Island and is thought to be nearly 200 years old, weighing over 150 kilograms. Aldabra giant tortoises are endemic to the islands of Aldabra and the Seychelles. In the 17th to 19th century, giant tortoises represented an important food source for sailors throughout the islands of the Indian Ocean and live individuals were often captured and stored for meat in the ship’s hold. In addition, habitat destruction and the introduction of alien species such as rats and goats further decimated the previously isolated populations. The Aldabra giant tortoise is one of only three giant tortoises in the area to survive today, and the only one to survive in the wild.

Despite their common name, hermit crabs are more closely related to lobsters than to crabs. They don’t have their own shell and adopt the empty shells of mollusks, swapping them for a larger shell as they grow. If seen out of a shell, hermit crabs have a bizarre appearance; the soft abdomen is twisted, which allows it to fit into the coils of the gastropod shell.

A ghost crab looks out from a small sand heap. These semi-terrestrial crabs are common in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world, inhabiting deep burrows in the intertidal zone. The name ‘ghost crab’ comes from their nocturnality and generally pale colouration.

A one-eyed land crab points to the sky at low tide. Thousands of these large crustaceans scuttle across the islands surrounding St Joseph lagoon.

The Bohar snapper is a species of snapper native to the Indian Ocean from the African coast to the western Pacific Ocean. It lives on coral reefs, and is found at depths from four to 180 metres. Adults often form large schools on the outer reefs or above sandy areas, mainly for spawning. They can reach a length of 90 centimetres and are one of the top predators within their ecosystem.

A blacktip reef shark swims over a mound of wart coral. The SOSF-DRC runs a long-term program that monitors the health of D’Arros’ coral reefs. Low-lying sandy islands are more prone to the effects of global warming than any other environment. Although sea level rise is the most obvious threat, increasing sea temperatures also accelerate erosion and result in habitat-altering sand shifts. Coral reefs are very important for stabilising the ocean floor.

Blacktip sharks are abundant off the coast of D’Arros. These and other shark species are being monitored by the SOSF-DRC. The centre manages 70 acoustic receivers that extend to the furthest reaches of the Amirantes Bank. More than 70 sharks have been tagged so far.

Great barracudas can exceed 1.5 metres and weigh over 23 kilograms. They possess massive, fang-like teeth. Barracudas appear in open seas and are voracious ambush predators.

Marbled groupers are long-lived and have a fascinating and complex life-history. They live for over 40 years, and become sexually mature at around 10 years. They aggregate in large groups to spawn. Scientists believe that this fish may be ciguatoxic, which means that their flesh could make humans very sick if consumed.

Potato bass are bold and inquisitive reef fish that may grow as large as two metres, but are really quite friendly creatures. They are also protogynous hermaphrodites; they start out as females, but undergo a sex change later in their lives and become males.

Longfin bannerfishes are social fish, and are found in pairs or in shoals. They are a very passive and some even act as cleaners, especially when young, by removing parasites from other fish. They mostly eat plankton.

Batfishes are endemic to tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In the wild, the batfish is found in brackish or marine waters, usually around reefs, at depths from five to 30 metres.

Hawksbill turtles are a small sea turtle species. They grow up to about 114 centimetres in shell length and 68 kilograms in weight. They are common in the ocean surrounding D’Arros Island. Since ancient times, their beautiful carapaces have been in demand for ‘tortoise shell’, which is in fact Hawksbill shell. These gentle animals were so severely persecuted that they are now listed as Endangered. The tortoise shell trade was banned by CITES in 1973.

The SOSF-DRC is currently running an ecological survey that will allow them to determine how stingrays, like this fantail stingray, live. They want to learn about their population demographics like relative abundances and sex ratios, their diet, and how they move around in the lagoon. By the end of the year, researchers hope to tag at least 30 stingrays, including fantail stingrays, porcupine stingrays and mangrove stingrays.

.jpg)