Oceans of hope

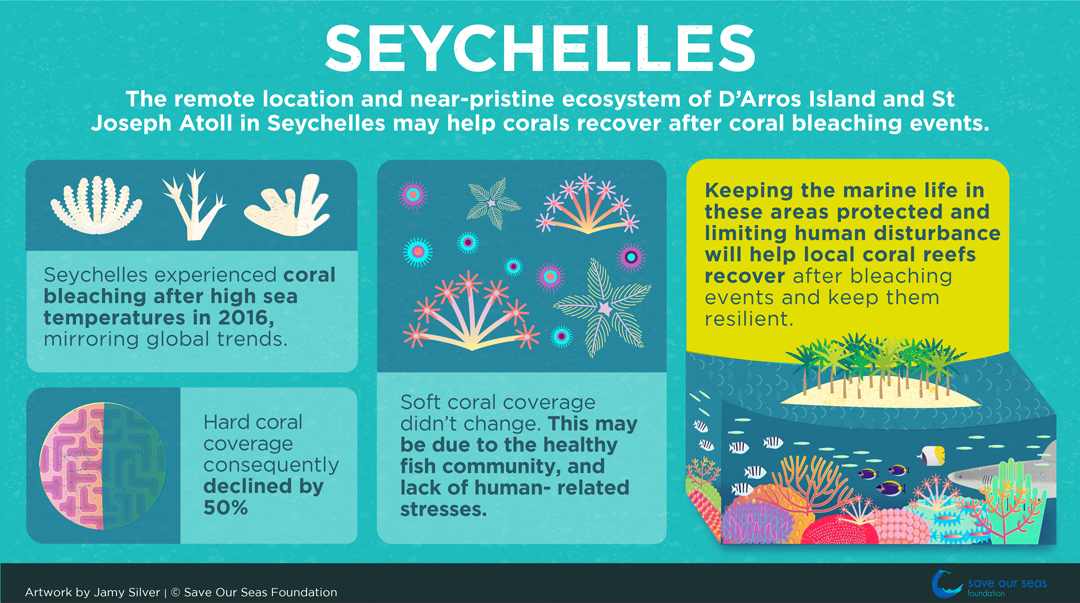

Research shows that bleached corals may recover at D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll, Seychelles.

“Seeing the changes to the reef was devastating”, begins Clare Daly, former programme director of the Save our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC) in Seychelles. “The sort of stuff that makes you wonder: ‘is it worth doing this kind of research?’ simply because there is so much sadness that comes with seeing the scale of these changes to our environment”.

Photo by Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

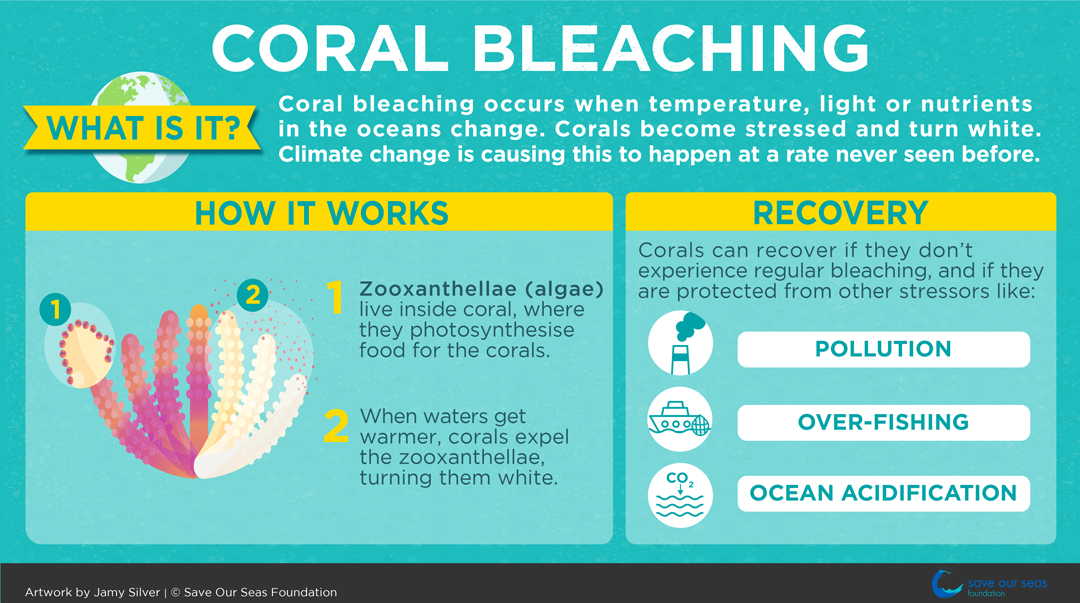

A worldwide coral bleaching event over the course of 2015 and 2016 devastated much of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and shallow tropical reefs around the globe. It was the most severe and widespread event of its kind on record. But were all places really impacted equally? And how do we assess and understand what the effects of this bleaching episode were for coral reefs and the communities they support, especially given that we can expect our warming world to repeat these episodes more frequently in the future?

Elena Gadoutsis assesses the condition of the coral reef. Photo by Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

These are the kind of questions that prompted the publication of a new study: “Post-bleaching mortality of a remote coral reef community in Seychelles, Western Indian Ocean” in the Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science. Clare is a co-author on the paper, which was written by Elena Gadoutsis from the University of York, together with Dr Ryan Daly (Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI) and former Research Director of the SOSF-DRC) and Julie Hawkins (also University of York).

Photo by Rainer von Brandis | © Save Our Seas Foundation

The study documents the changes in the type and condition of coral cover on the shallow reefs around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll, over the period starting just prior to the global bleaching episode in 2015, until just after raised sea temperatures subsided in 2017. The findings point to the possibility that the coral reefs around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll in the Amirantes region of Seychelles may have fared better than other areas in the world, and might have a chance of recovery.

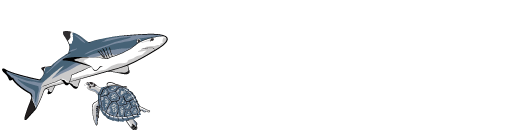

Artwork by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Near-pristine and remote, the ecosystems around these islands are protected from pollution, overfishing and coastal development: stressors that would reduce the coral reefs’ capacity to adapt to a changing climate and recover from a major bleaching event. Interestingly, it’s a conclusion that echoes some of what the other researchers in the region have suggested; from the work of Ornella Weideli, whose research on shark pups shows the value of the area’s remote location and healthy condition for young sharks, and Lauren Peel, who has identified that manta rays that return with regularity to these important reefs.

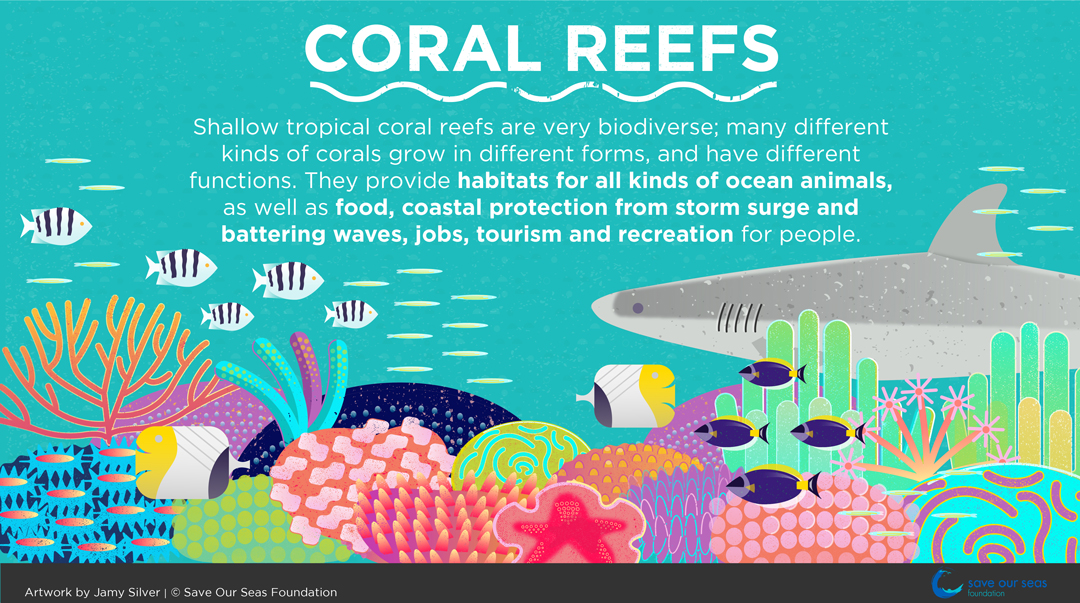

Artwork by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

“At the SOSF-DRC, we collected data on the coral reef cover around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll for a number of years”, explains Clare. From recording the surrounding sea surface temperatures, to deciphering the fish communities that swim over these reefs and counting the extraordinary diversity of invertebrates that call these coral atolls their home, the scientists detailed a holistic picture of D’Arros Island and its surrounds. Doing so gave them a reference for what the region looked like before and after the rising sea temperatures of the 2015-2016 period.

The study reports that the reefs around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll lost nearly 50% of their hard coral cover after the 2016 coral bleaching event. But there were some surprising elements to the researchers’ discoveries. This substantial decline is certainly what prompted Clare’s despair: “And yet,” she continues, “Once we analysed the data from the whole survey region, we could see that there was actually potential for recovery in this area, and that the results were different from what had happened elsewhere. That was motivating; the kind of impetus one needs to carry on with research. It’s hopeful”.

Artwork by Jamy Silver | © Save Our Seas Foundation

The hope she speaks of lies in the study’s other results, which show that while many hard corals were lost, the whole seafloor community didn’t shift to one dominated by eerie white rubble or the shaggy cover of algae that tend to take over after corals die. In fact, some of the sites surveyed showed little mortality of corals of any kind. And those deeper reefs, experiencing slightly cooler temperatures and covered in the kind of corals that are more resilient to temperature fluctuations, lost less hard coral cover to bleaching.

Scientists at the SOSF DRC continually monitor the reef ecosystem around the island. Photo by Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

“We need constant monitoring. If we’re not keeping tabs on these ecosystems before degradation happens, and only start looking at them after we know we’ve hit a crisis, we can’t compare the condition of coral reefs. And if we don’t have that information, we can’t go to policymakers with a true reflection of the baseline”. Clare’s explanation speaks to another key suggestion from the paper: while devastating, the decline in hard coral cover from 28.5% in 2015 to 14.7% in 2017 still means that there are some corals left to recruit new growth. This might mean that hard coral reefs recover slowly in the coming years around the Amirantes. Additionally, the scientists reported increases in coralline algae after the bleaching event, which may actually help the hard coral reefs recover. “The baseline has shifted. But you have to have documented the original baseline first, as we go forward”, concludes Clare. “There is no going back. But at least we know our point of departure”.

Sharks are an indicator of healthy coral reefs. A blacktip reef shark patrols a reef around D’Arros Island. Photo by Ryan Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Keeping fish populations stable and well-managed, and limiting the amount of human disturbance around D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll, will go a long way to helping these coral reefs recover. In fact, the stability of the type of seafloor cover might be the result of a thriving fish community that grazes the algae on the reefs, and few stressors other than rising sea temperatures in this region. In our increasingly warming world, the future of coral reefs might well rely on having places like D’Arros and St. Joseph Atoll where the marine ecosystem is resilient to crisis events: remote, or well protected, to offer reefs some reprieve.