From the Field to the Lab

What comes after the fun in the field? SOSF-DRC Project Leader Chantel Elston sheds light on the transition from her atoll attire to a lab coat. Her extensive research on stingrays in St Joseph Atoll requires a lot of lab work. Here she provides a glimpse of the other side of fieldwork.

The largest feathertail stingray caught on Chantel's final fieldwork season in St Joseph Atoll. The data collected from this ray will contribute to her PhD on stingrays in the atoll. Photo by Clare Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

There will inevitably come a time in your project’s life when all of the fun stuff is finished – all of your fieldwork has been accomplished and all of your samples have been collected. This is quite a bittersweet moment – you’re happy that you managed to accomplish a successful field season (this is always difficult because when working in the ocean there are plenty of opportunities for things to go wrong), but you’re sad that you have to trade in your outdoor office for an indoor based office. This moment happened in August 2015 for me, and since then I have been keeping busy with the ‘indoor’ side of my project.

Chantel examines the fresh stomach samples of a stingray in St Joseph Atoll. Photo by Clare Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Our final field trip in 2015 proved very successful – we managed to catch a total of 117 stingrays in 2 weeks. Previous field trips had yielded the collection of stomach content samples from porcupine rays, but our final trip was dedicated to capturing and collecting the stomach contents of the other two species of stingray present in the atoll (feathertail rays and mangrove whiptail rays). This is important so that we can see how these species interact within this isolated environment and whether they have to compete for limited resources or whether there is enough of the prey to ‘go around’. In addition, we collected muscle samples of all three species on this trip. So what in the world did I need muscle samples for and what happens after the field work is finished?

The smallest feathertail ray caught on the final fieldwork of Chantel's research. Photo by Clare Daly | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Well, next up on the agenda was to analyse the samples I had collected and sometimes one needs fancy lab equipment to perform these analyses. So in April 2016 my samples and I were lucky enough to make our way to the University of Windsor in Canada. Here I worked under the expertise of Aaron Fisk and the wonderful people in the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research. I spent two weeks preparing the stingray muscle samples so that they could be run through a mass spectrometer. This piece of equipment tells us the ratio of heavy to light carbon and nitrogen isotopes (which are the same atoms but with different numbers of neutrons) of the stingray muscle, and these results will enable me to broadly identify what the stingrays are eating and if they change their diet as they grow older.

Chantel prepares the stingray muscle samples to be run through the mass spectrometer at the University of Windsor, Canada. Photo by Tanya Elizabeth

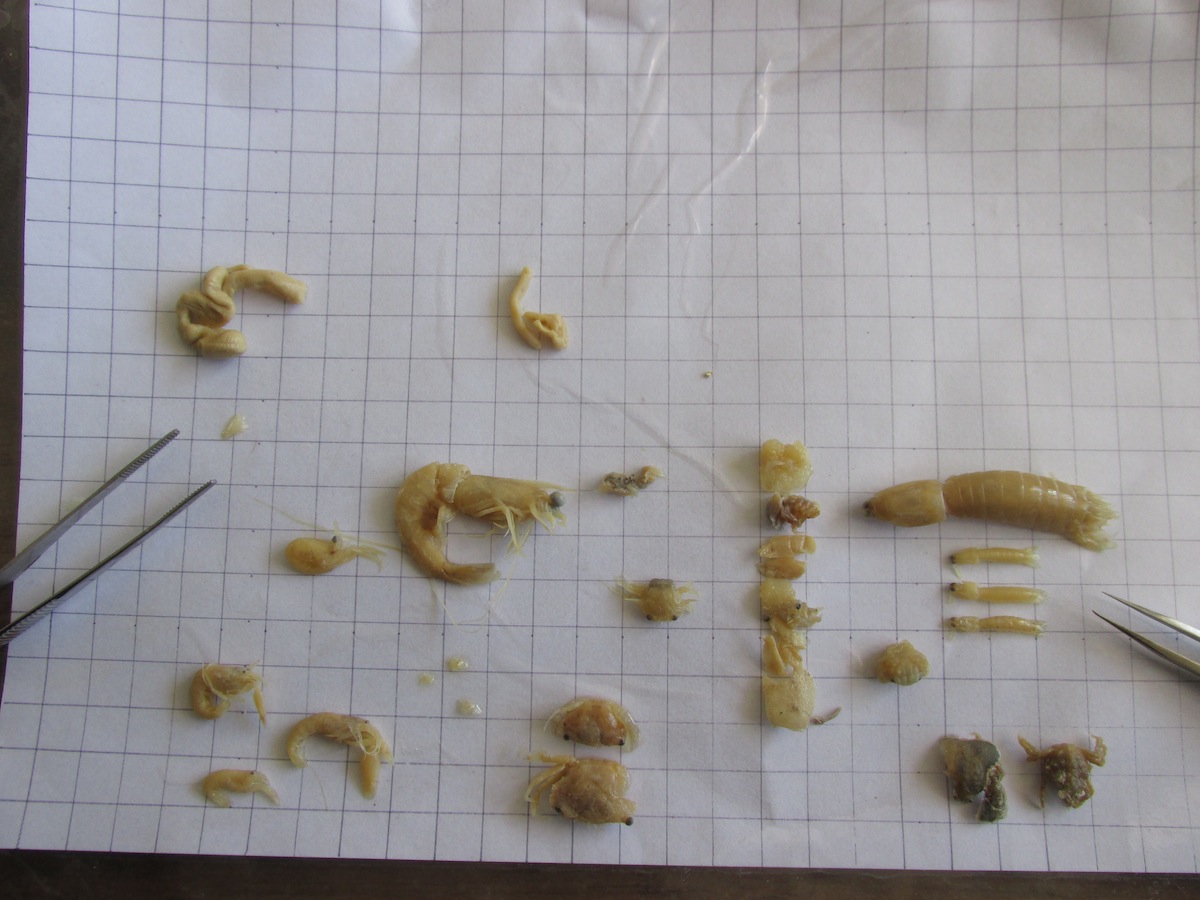

Once back home after a successful lab trip, I had the stomach content samples of the feathertail rays and the mangrove whiptail rays to work through. For this I didn’t need any fancy equipment, just a nose plug (these samples don’t exactly the smell the best!) and a dissecting microscope to identify the prey items. The results of the stable isotope analyses (using the mass spectrometer) and the visual analysis of stomach contents will complement each other and give me a much better understanding of the dietary habits of these stingrays.

A variety of prey items collected from the stomach sample of a feathertail ray mainly includes shrimp and crabs. Photo by Chantel Elston | © Save Our Seas Foundation

This is important information to gather as stingrays play important roles within the ecosystems that they occupy, as does any predator. Stingrays, in all likelihood, make up the bulk of the animal biomass within the St. Joseph Atoll and figuring out what these species eat will help us begin to understand this ecosystem and begin to see what the food web of the atoll looks like.

So at the moment, I’ve collected all my samples, I’ve analysed my samples and collected the necessary data, so the next step? A lot of behind-the-computer time analyzing this data to figure out the answers to my questions.