What is a Colour Front?

Cape Point marks the southwestern tip of the African continent, with some of the most breathtaking ocean and coastal scenery in the world.

The treacherous rocky reefs surrounding the Point are home to 26 recorded shipwrecks – and probably many more. Sea cliffs rise over 250 meters above the waves crashing against the rocks far below.

You may have heard of Cape Point referred to as the place where two oceans meet, or even seen this distinct colour line in iconic images. But what really is the cause of this phenomenon? Why does the ocean close to Cape Point often appear to be split in half, displaying two distinct colours on either side of an invisible boundary line?

A typical ‘colour front’ close to Cape Point. Captured by local Cape Town photographer Jean Tresfon.

Colour Fronts

The ocean surrounding Cape Town is dynamic and ever-changing. Some days you might dive in and find crystal clear water with top-to-bottom visibility, and others, you can’t even see your hand in front of your face.

The reason for this is due to a natural phenomenon called ‘colour fronts’, where from the surface, the ocean is marked by runways of sharply contrasting coloured water.

In oceanography, a front is an interface or boundary between two separate water masses. In this case, the water masses are easily discerned because they are different colours. There are usually other water properties on each side of the front that differ, too, like temperature, salinity (how salty the water is) and density.

Fronts are either convergent (the water masses move towards each other) or divergent (water masses move away from each other). Usually, the presence of marine debris, like pieces of kelp or sediment, at the front boundary suggests that it is convergent, as the kelp is pushed to the middle.

What is causing this?

‘Colour fronts’ have been severely understudied. Prior to 2005, there was much conjecture about the causes of this phenomenon, including the usual pollution culprit, but little evidence to support any of the theories. It was on the ‘Learn to Dive Blog’, a former Cape Town-based dive centre, where we learned a bit more about the history of these occurrences.

When a large, obvious colour front arose near Simon’s Town in November 2005 with milky green water on one side and darker blue-green water on the other, researchers from UCT and IMT sprang into action, sampling the water on each side of the boundary so that they could measure its properties. Speed is of the essence in these situations, as ‘colour fronts’ can disappear quickly. The one in the picture below is busy decaying – notice the smudged boundary.

Measurements revealed that the milky green water overlaid the clearer, bluer water down to a depth of 11-12 metres (this will vary from front to front). The milky water did not extend to the ocean floor. Cape Town divers might be familiar with diving through “thermocline” patches, two or more layers of water with varying visibility and temperature!

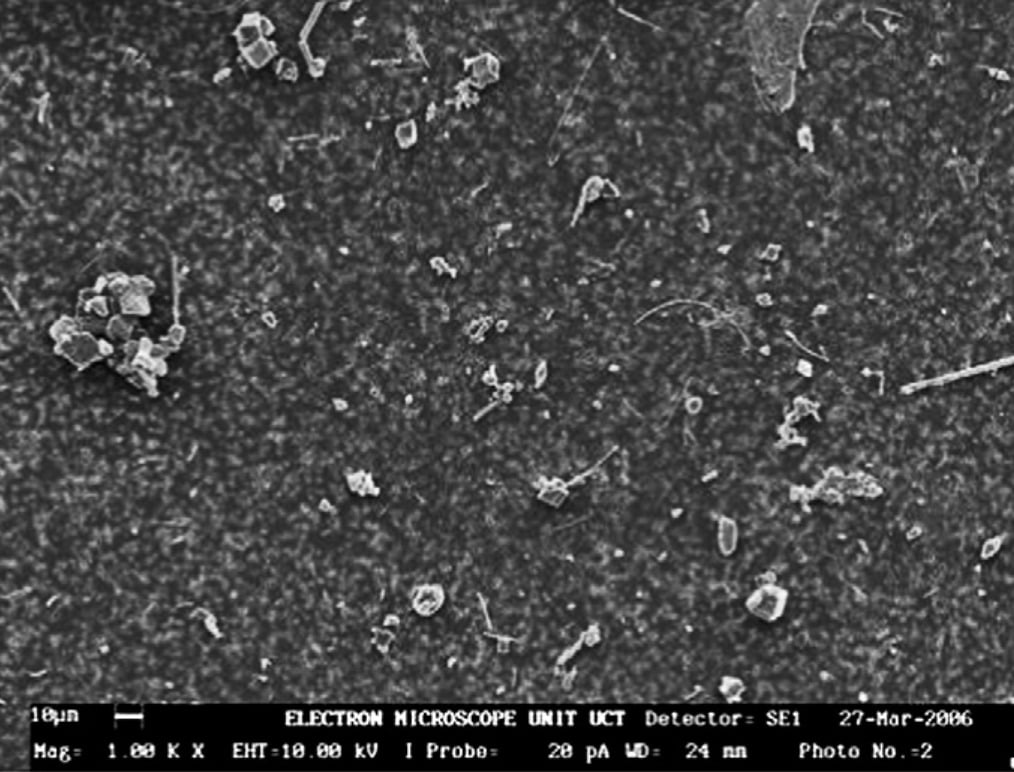

The researchers found that the milky-coloured greenish water was full of fine, almost neutrally buoyant particles of calcium-rich sediment. The green-blue water contained much less calcium but relatively more silicon, suggesting the presence of diatoms (a type of phytoplankton – you can think of them as teeny tiny plant-like organisms). The origins of the calcium-enriched sediment in the milky water are interesting: one source is from the shallows (less than 30 metres deep) of the northwestern corner of False Bay, where the ocean floor is made up of rocks that are rich in calcium carbonate (such calcrete and limestone), some areas covered by a thin layer of sand.

Scanning electron microscope images of green-blue water containing much less calcium but relatively more silicon, suggesting the presence of diatoms. Image from the paper 'A Prominent Colour Front in False Bay: Cross-frontal structure, composition and origin'.

The second probable origin for the particles of calcium-rich material is the interface between the sea and the land at the northern end of False Bay. The cliffs at Wolfgat/Swartklip at the head of the bay are made of calcrete, and at Swartklip, the beach narrows to the extent that the cliffs erode directly into the water when the sea is high. Strong southerly winds create a wide surf zone at Muizenberg and Strandfontein; a spring tide also adds to ideal conditions for generating a colour front.

Wolfegat/ Swartklip is situated near Mitchells Plain, along the shores of False Bay. Image by mapio.net.

The temperature of the milky water at this location was found to be slightly (0.4 degrees Celcius) higher than the green-blue water. This value will also vary between. The researchers speculate that the temperature difference could be because the milky water originated in the surf zone, which is shallower and therefore warmer, or because the high concentration of suspended particles in the milky water caused greater absorption of heat from the sun.

Should we be worried?

Contrary to what you might find on social media, not all colour changes in the ocean around Cape Town is caused by large sewage spills. In fact, most of them can be explained by completely natural biological processes.

In summer, the reason for the ocean looking green, red or even brown is likely to do with a plankton bloom or related to suspended sediments (as in this case) or other naturally arising material in the water.

A surf-zone diatiom bloom (type of phytoplankton) at Muizenberg beach along the shores of False Bay. Image by Danel Wentzel.

The ocean surrounding Cape Town is incredibly dynamic and teaming with life on all scales. Instead of boasting about pollution spills, which we do know is a real issue, why not spend some time celebrating how truly amazing the biological process are in the ocean?

Dip your face in the water and see what it does to the viz. Take some pictures for posterity. And – if you don’t know what’s causing it – try to find and question someone who does know, like a scientist, or consult a good non-fiction book to find out some facts.

In a seashell,

This phenomenon is known as a colour front. They are formed during strong southeasterly winds, which set up an extensive surf zone along the northern end of False Bay, and in turn, disturb the sediment on the ocean bottom, driving the waves further up the beach than usual.

Particles of buoyant calcium carbonate from the sea floor and eroded from the cliffs are lifted into the water column, changing its colour to a milky-green shade. Wind-driven circulation patterns in the bay push the front from its original location towards Simon’s Town.

Contrary to what social media may claim, not all colour changes in the ocean around Cape Town can be attributed to giant sewerage spills. These are natural phenomena, and we should celebrate this incredibly dynamic system that can be observed living near the ocean!

If you’d like to read more about colour fronts in False Bay, take a look at this scientific paper (pdf), which was used as a source for this post. The paper is called A Prominent Colour Front in False Bay: Cross-frontal structure, composition and origin.