Shark Centre facilitates scientific research and hosts international researcher

The Save Our Seas Shark Centre welcomed Sevengill shark researcher, Adam Barnett, during a 2-week visit in March while he and Alison Kock made headway on their new shark project in False Bay.

A little more about Adam…

Adam has worked in a number of jobs associated with the marine environment encompassing scientific research, education on an eco-tourism dive vessel and as a member of production teams on 20 underwater documentaries. In 2006, Adam moved to Tasmania, Australia to undertake a PhD on Sevengill shark ecology, which was partially funded by SOSF and was completed in 2011. Adam has been looking at the role Sevengills play in the temperate ecosystems in Tasmania, and is now expanding the project in Australia to incorporate the whole of the east coast from New South Wales to Tasmania. He is also trying to set up a project in Port Phillip Bay, which will focus on the Sevengill pups.

Currently, Adam holds research positions at Deakin University in Melbourne, the Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies in Hobart and the Reef Channel, North Queensland.

Why Adam chose to study Sevengills?

The last person to complete a large study on the Sevengills was Dave Ebert with his PhD in the 1980’s. There hasn’t been much interest in them since, only a few smaller studies in Argentina and Southern Australia. This is surprising as Sevengills are found in most temperate waters except for the North Atlantic, and are a coastal species that appear to be abundant and easy to catch.

Somehow this species has been overlooked. Whites sharks are referred to as being the apex predator at the top of food chain, however Sevengills eat the same prey and there appear to be more of them. So could they have a greater influence on the ecosystem than the Whites?

Previously their diets were studied and some small reproductive work, but there has been no real focus on their ecology and role in ecosystem, until Adam’s work in Tasmania.

A little more about Sevengills…

The broadnose sevengill shark, Notorynchus cepedianus, is a large (up to 3m) coastal-associated apex predator with a wide temperate distribution. This species’ trophic position rivals that of other species considered important upper trophic predators such as tiger sharks and white sharks (Cortés 1999; Barnett et al. 2010b; Barnett et al. 2012). Yet, in contrast to the latter two shark species, considerably less information is available on Sevengill sharks.

Sevengill sharks are a low value fishery species across their global distribution. However, there are no management policies or conservation considerations for this species in any country, and exploitation is currently unrestricted. Ongoing unregulated exploitation is of concern, as previous targeting of Sevengills in California and Namibia suggests vulnerability to fishing (Barnett et al. 2012).

Their low conservation priority may be attributed to the lack of available data (classified as data deficient on the IUCN Red List). For example, in South Africa, scientists have noticed reduced catches, but efforts to form management strategies are hindered by this lack of data. In the Southern Australian shark fishery, they are at high risk in terms of abundance and catch susceptibility, with current fishing mortality rate estimated to be higher than the maximum sustainable levels (Zhou et al. 2007).

Are Sevengills a threatened species?

Worldwide, the Sevengills are a bycatch species in commercial fisheries and are also targeted by recreational fisherman. Currently there are no conservation management plans in place for them and there is concern in South Africa that they are being affected by fishing. One of the aims of this project will be to collect enough data to inform management as to whether any threats exist.

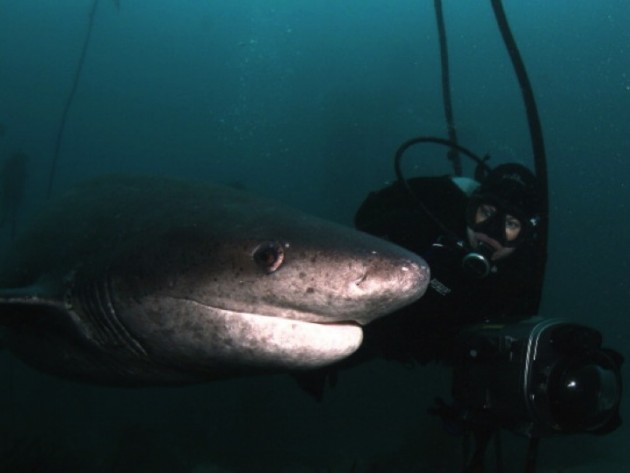

Alison diving with a Sevengill at the aggregation site, up to 70 sharks can been counted on a single hour long dive

Why is False Bay so unique?

Adam and Alison are looking to see what the Sevengills are doing in False Bay and how important this ecosystem is as an aggregation site. False Bay is unique in that it is the only place in world where large numbers of Sevengills (up to 70 on a single dive) can be consistently seen. In all other instances, the water is so murky that there is little visibility or sightings are few and far between. Another factor is that it is suspected that pregnant females reside here. There is little known information on pregnant females elsewhere in world so this presents a great opportunity to collect more data which will be done by using non-destructive methods, for e.g. analysing hormones in the blood samples that are collected.

How much has been done on the False Bay project so far?

This project plans to track the sharks using acoustic tags and receivers. With the expected 10-year battery life of the tags, the research team is hoping to give the project a long-term focus and extend this out of False Bay to other areas of South Africa. In collaboration with Dr. Paul Cowley from the South African Institute of Aquatic Biodiversity and the Ocean Tracking Network, migration patterns along the South African coast can be determined using an existing array of acoustic receivers.

The pilot phase of this project is to deploy the acoustic receivers (which was done when Adam visited in November 2012) and to tag the Sevengills (which they have started on this March trip), so that they can determine whether or not they need to move the receivers in the bay to maximize the data collection. Alison will be downloading the receivers in June, so they will start to get an idea on the sharks movements in False Bay then, while Adam will return in November to tag more Sevengills.

The Sevengills will be acoustically tracked together with the White sharks at Seal Island and around False Bay. With up to 75% of the Sevengills diet being seal, Adam and Alison are hoping to determine where the Sevengills are hunting seal, and whether or not they visit Seal Island, and if they do visit the island, do they do so while the Whites are there, or wait till spring and summer when the whites are less prominent at the island.

During this March field trip, 13 Sevengills were tagged and blood and tissue samples were collected for stable isotope analysis, which allows the scientists to determine their diet, and for reproductive hormone analysis, which allows them to assess maturity status and reproductive seasonality.

Sevengill held upside down in the water to keep the shark calm and ensure water flowing over the gills at the same time

As with all successful projects, a strong team of collaborators are involved including Adrian Hewitt (UCT and Shark Spotters), Dr. Malcolm Smale (Bayworld), Meaghen McCord and Tamzyn Zweig (The South African Shark Conservancy), Charlene da Silva (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries) and Dr. Paul Cowley (SAIAB and OTN). The main sponsors of this project are The Two Oceans Aquarium who have donated tags, manpower and funding and Ocearch who have also donated tags. The Save Our Seas Shark Centre has offered accommodation to Adam at the Shark Centre during his visits for field work.