Keeping record of our feathered friends

Birding, the art of finding and identifying different bird species, either in your backyard or a couple 1000 kilometres away from home, is a growing hobby among many young naturalists. Not only is it a great way to learn more about the birds around you and get some fresh air, but with accurate records, it can be used to monitor changes in behaviour, migratory patterns or population distribution and/or growth of different bird species. This is particularly important in light of global climate change which has led to a loss of habitat (where changes may eliminate essential breeding or stop-over grounds), changes in wind regimes (which may make pre-existing migratory routes less optimal), changes in the temperature of the ocean (contributing to shifts in the distribution and abundance of prey species for many seabirds) together with sea level rise (further reducing available habitats). Together with anthropogenic pressures (such as habitat destruction, pollution and pressures from fisheries) if birds don’t ‘make-a-plan’ they may become extinct – and will no longer be around for us to appreciate or more importantly fulfil their biological role in the environment.

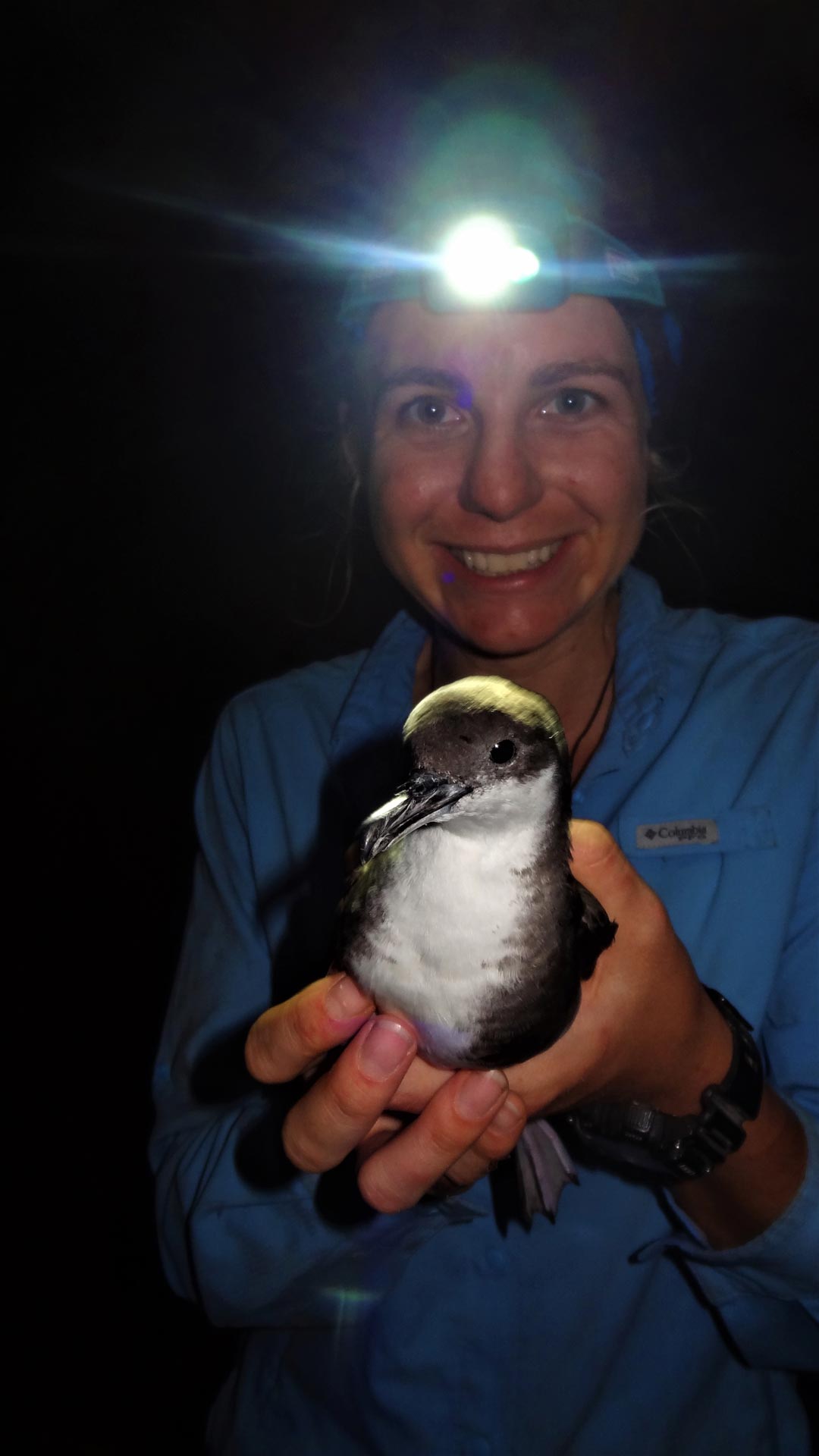

In between the thousands of wedge-tailed shearwater burrows, we came across the much smaller Tropical shearwater. Photo by Luke Gordon | © Save Our Seas Foundation

While working on D’Arros Island and in the St Joseph Atoll I was privileged to observe many different bird species, many of which were Iifers (birds that you see for the first time ever). These birds consisted of native species (the locals) such as the Seychelles fody, white tailed tropic bird, fairy terns, lesser- and brown noddies as well as the grey and green-backed herons. These birds breed throughout the year on the islands and do no migrate to other areas.

The White-tailed tropic bird is esily identified with its thin long tail. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Resident green-backed herron in breeding plumage. During the non-breeding season, they have green legs, but apparently red legs are more attractive to the ladies. Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Brown noddy, often confused with the lesser noddy, however this bird has a shorter bill. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

The fairy tern is the only completely white tern. They do not lay their eggs in nests, but rather on bare branches. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Many red-footed and brown boobies, lesser and greater frigate birds as well as sooty terns breed in other areas Seychelles, but come to roost in the Casuarina trees of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll.

Male lesser frigate bird soaring through the air. These birds have the lowest wing loading of all birds and can stay on the wing for hours, even sleeping in flight. They also harass other birds for their food when they return to the island. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Two inquisitive brown boobies roosting in a Casuarina tree. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Sadly, a few exotic species have also made their way to the islands. Though not all of them are invasive (displace the locals) like the Madagascar barred dove and Madagascar turtle dove, some are more belligerent species like the house sparrows dove have taken over habitats used by the local Seychelles foddies.

Figure B. The red male Madagascar fody (Figure A) and the yellow Seychelles fody (Figure B). Both these birds fill the same niche in their environments, explaining why they do not co-exist well. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Some birds come to these islands to breed, like the wedge-tailed shearwater, black-naped tern as well as the rosette tern and possibly the tropical shearwater and greater crested tern. They make use of productive waters nearby during October – December which are influenced by the seasonal trade winds.

Greater crested tern (also known as a swift tern) looking for small fish to eat. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

These back-naped terns are often seen standing on floating objects in the water, like these buoys. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Wedge-tailed shearwater in its underground burrow. Unlike most ‘normal’ birds, wedge-tailed shearwaters build their nests underground and use their specialized webbed feet to burrow. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Many migratory birds travel long distances from their breeding grounds in the Arctic, North America, Europe or Asia to their over-wintering grounds in the tropics. Some spend their entire overwintering period in Seychelles, while others only use it as a stop-over point on their way to East-Africa or further south. Some of the ‘jet-setters’ I spotted while working with the D’Arros Research Centre (DRC) included the crab plover, terek sandpiper, whimbrel, Eurasion curlew, greenshank, ruddy turnstone, grey plover, Pacific golden plover, common sand piper, curlew sandpiper, lesser and greater sand plovers, common ringed plover, marsh sandpiper, black-winged pratoncole, wood sandpiper, sanderling and the bar-tailed godwit. Thanks to the help of the Program Director, Clare Keating Daly, I was able to identify many of these species, which is much harder than you think. But, once you have you ‘eye-in’ it all becomes easier.

This little terek sandpiper was the first on D’Arros for some time and the record was added to the Seychelles Bird Record Committee (www.seychellesbirdrecordcommittee.com/blog) Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Eurasian curlew skulking around. These birds have a disproportionately long bill, making them look slightly off balance. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Greater sand plover feeding amongst some cardisoma crabs. This seems rather risky between all those large pincers. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

A bar-tailed godwit in flight. These birds are easy to identify since their bills curve skywards. Photo by Danielle van den Heever | © Save Our Seas Foundation

Many scientists rely on citizen science, which is the involvement of members of the community in scientific research, to report sightings of different bird species to local or international birding committees or specific programs. So, if you ever notice something strange going on in your area, let someone know, you may have stumbled across something novel.