Super-shrimps & more

—

In my previous blog I talked about some of the terrestrial invertebrates that we come across at D’Arros Island. When someone says invertebrate I automatically think of bugs. However, there is a vast diversity of creatures under the sea that don’t have a back bone either.

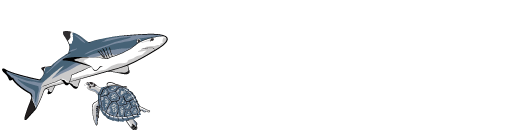

Surprisingly, sea sponges (Porifera) are invertebrates – it’s true, sponges are animals. (Figure 1) They are the most basic of marine invertebrates and have been in the ocean for more than 500 million years. These very simple, multi-cellular organisms have no head, eyes, brains, arms, legs, ears, muscles, nerves or organs. Yet despite all their shortages in the appendage and sensory departments, they are master filter-feeders. In fact, filter-feeding is their sole function. They filter an amount of water up to 100,000 times their size each day. A sea sponge’s body contains thousands of pores that allow water to flow through it continuously.

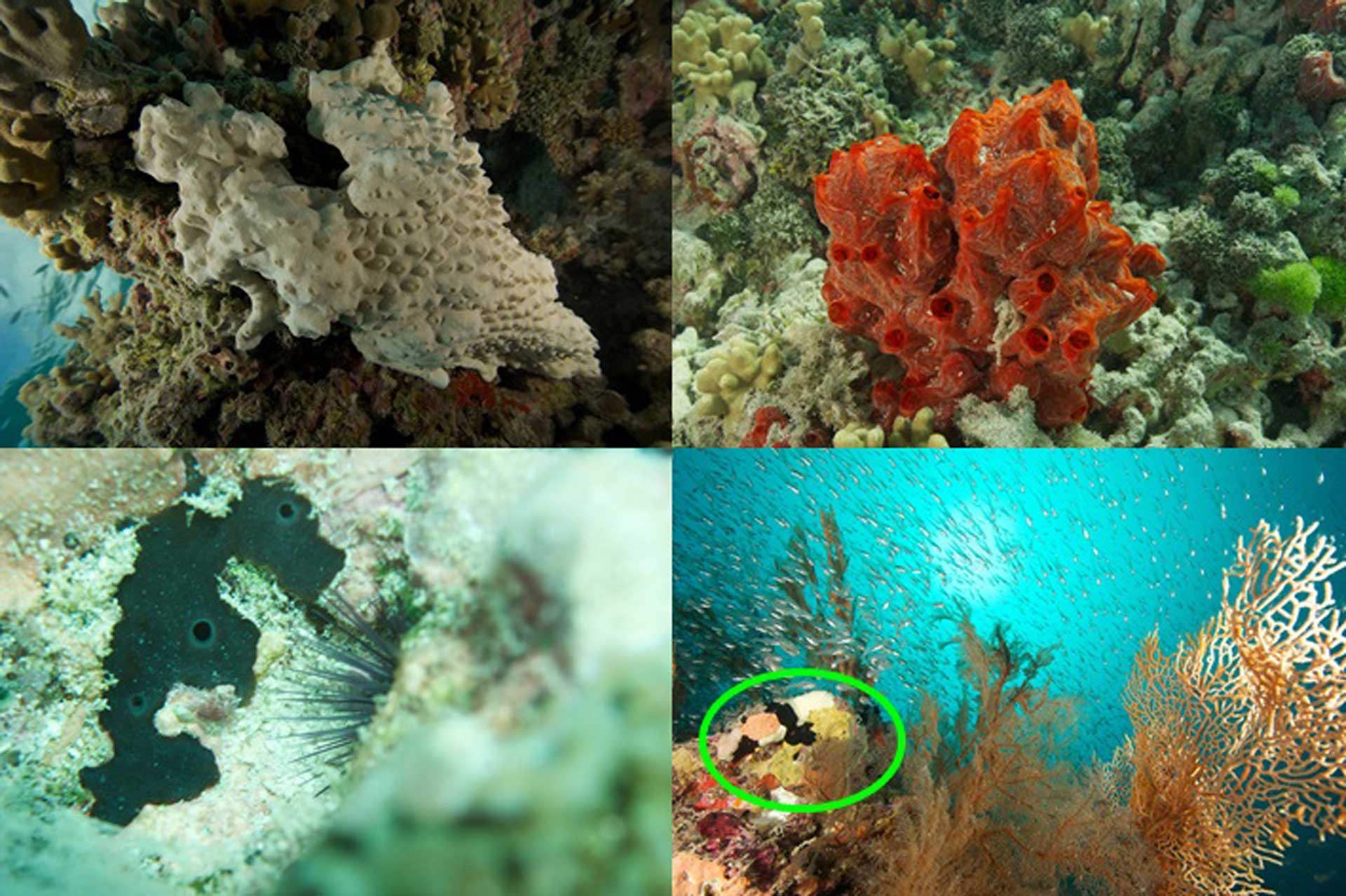

Sea cucumbers (Holothuriidae) are also basic invertebrates that are perfectly adapted to marine life. (Figure 3) These odd, squishy, cucumber-shaped creatures have no brain, but they do possess a very complex nervous system. They have no sensory organs, however, and have to rely on programming and instinct. Unable to vocalise, sea cucumbers can communicate with one another only by releasing hormones into the water. They are vitally important to the community structure of coral reefs because they are macro-detritivores (organisms that feed on dead plant and animal matter) and consume organic detritus. (Figure 4) Late maturity, density-dependent reproduction and low rates of recruitment make sea cucumbers susceptible to overexploitation, so it is important to detect any changes in their abundance.

The octopus (Octopoda) is renowned for having eight legs – or, more specifically, four pairs of arms. (Figure 5) It has been recognised as being one of the most intelligent and behaviourally diverse of all invertebrates. Even its body structure is more intricate than most: an octopus has three hearts, two of which pump blood through each gill while the third pumps its blue blood through the body. This predator actively hunts a variety of organisms, using its speed, impeccable camouflage and ability to squeeze into the tiniest crevice as aids. It captures prey with its arms and draws it towards its beak-like mouth in the centre of its body. There it usually injects the prey with paralysing saliva before tearing it into small pieces with its beak. When an octopus in turn is attacked by a predator, its escape strategies include speed, camouflage and mimicry. It may also squirt a disorientating ink cloud at its attacker or, if all else fails, it can sacrifice an arm while the rest of it gets away – and then regenerate the missing arm. Studies have shown that octopuses learn easily, including by observing another octopus. They can solve problems and can, for example, remove a plug or unscrew a lid to get prey from a container. And octopuses were the first invertebrates seen to use tools!

The octopus may be smart but the mantis shrimp (Stomatopoda) is the coolest of all marine invertebrates. (Figure 6) It may not have a back bone in the literal sense, but it is definitely no wimp. This super-shrimp is a swift, tough and effective death machine of the sea. Pound for pound, the mantis shrimp is one of the strongest animals in the world. It uses its club or spear (depending on the species) like a fist to punch, or spear, its prey. The force with which it strikes is similar to that of a bullet shot from a .22 calibre firearm. This incredible force is a vital part of the shrimp’s hunting strategy, being used to break the shells of crabs and clams. Researchers have found that the club of a mantis shrimp is spring-loaded, as in a crossbow: when released it accelerates at more than 80 kilometres (50 miles) per hour with a force of over 150 kilograms (330 pounds), or up to 2,500 times the shrimp’s own weight. If this shrimp were the size of a person, it could hit hard enough to break steel! Scientists keep caught mantis shrimps in strong plastic tanks because their punch would break a glass tank. More than strong, the strike of a mantis shrimp is unbelievably quick. In the time it takes a person to blink, this fearsome shrimp can, in theory, deliver 500 punches. But wait, there is more: the mantis shrimp has the broadest visual spectrum of any known animal. (Figure 7) It has trinocular vision (it can see an object using one of the three different parts of the eye) and it can also make out ultraviolet and polarised light. This invertebrate is definitely one for the record books!

Each year, members of the D’Arros Research Centre conduct a survey to monitor trends in the abundance of mobile invertebrates, recording octopuses, moray eels, giant clams, sea urchins, large shells, large crustaceans, sea cucumbers, starfish and nudibranchs found in the transect. These invertebrates can act as indicator species, or organisms whose presence, absence or abundance reflects a specific environmental condition. Indicator species can signal a change in the biological condition of a particular ecosystem, and thus may be used as a proxy to diagnose that ecosystem’s health. Changes in invertebrate communities may occur as a result of fishing practices, climate change and changes in benthic composition. Population explosions of some invertebrates, such as the crown of thorns Acanthaster planci, can damage coral communities. (Figures 8 & 9) An increase in sea urchins (Echinoidea), on the other hand, can have a positive impact on the growth and settlement of corals, as they remove the algae that compete with corals for space. (Figure 10)