Like a fingerprint

Being able to recognise individuals within a population is often a starting point for ecological and conservation studies. It provides researchers with crucial information about:

– population size (how many individuals there are in a population)

– population composition (the sex and size of individuals in the population, for example)

– distribution (how individuals are spatially arranged and their movements)

– home range (the area in which an animal lives and travels) and territory (the area that is actively defended)

– population dynamics (rates of birth, death, immigration and emigration)

This is important information for the development of conservation strategies.

In order to identify individuals, external tags can be attached to them. However, there are drawbacks to tagging studies, such as stress to the animal during physical capture, alteration to the animal’s appearance and the limited lifespan of the tag, which could be damaged, shed or removed.

The use of photography to record animals’ natural markings has become an attractive and viable alternative to tagging, as it minimises disturbance to the study species. Identifying individuals from their natural markings has become widely used among biologists studying terrestrial species, such as by the spot patterns of cheetahs, the rosettes of leopards, the whisker dots of lions and polar bears, the stripes of tigers and zebras and the coat patterns of wild dogs. Even birds can be distinguished in this way: individual saddle-billed storks, for example, have a unique saddle on their bill that enables them to be identified.

Technological developments in the form of digital photography and housings for underwater cameras have opened up the possibility to expand this ID method to the marine world as well. Photo-ID techniques facilitate the non-intrusive monitoring of individuals of certain species by identifying and re-identifying them over short or long periods.

Species like the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricate, which is endangered, live in the waters around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll: females use the beaches to nest and juveniles find sanctuary in the atoll’s waters. The scutes (or scales) on their face are unique and can be used to identify individuals (figure 1).

Unique scutes on the face of a turtle. The scutes encircled in yellow are temporal scutes; in orange are post-ocular scutes; and in blue are tympanic and central scutes.

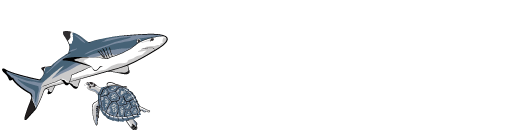

Manta rays Manta alfredi feed on plankton just offshore and the ventral surface, or underside, of each one has a unique spot pattern (figure 2). Studies in Japan and Hawaii have shown that the spots on mantas do not change for at least 30 years, which bolsters their usefulness as a ‘fingerprint’. The D’Arros Research Centre has identified 105 individual manta rays that have passed through local waters.

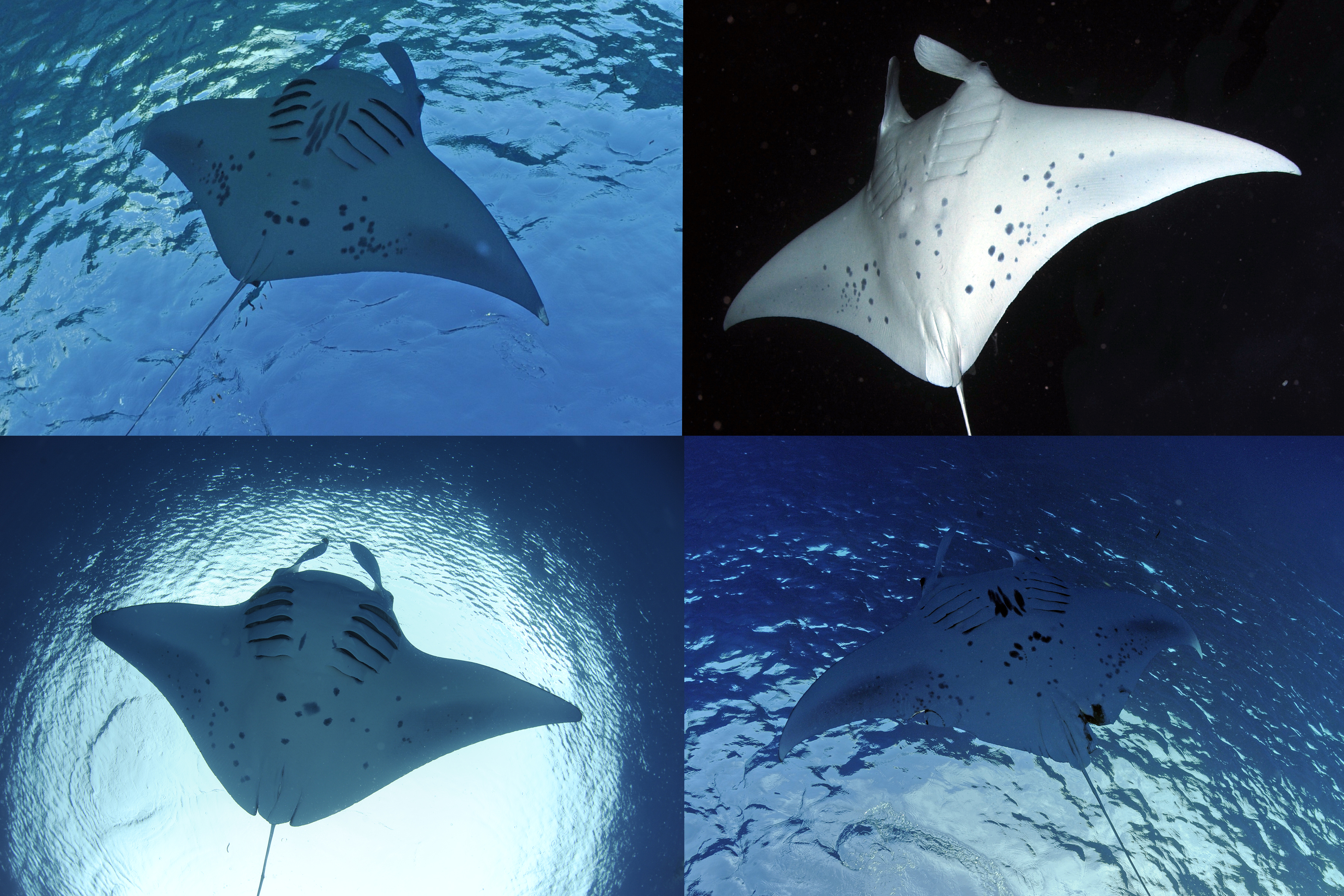

This photo-ID technique can be used on different shark species as well. The blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus, for example, has a dorsal fin that looks as if it has been dunked in a tin of black paint. The bottom margin of the black tip is unique to each individual (figure 3), which enables researchers to identify individuals as long as a photograph of each side of the fin is obtained or a selected side is used in the database (all the sharks have to be swimming in the same direction in the photo).

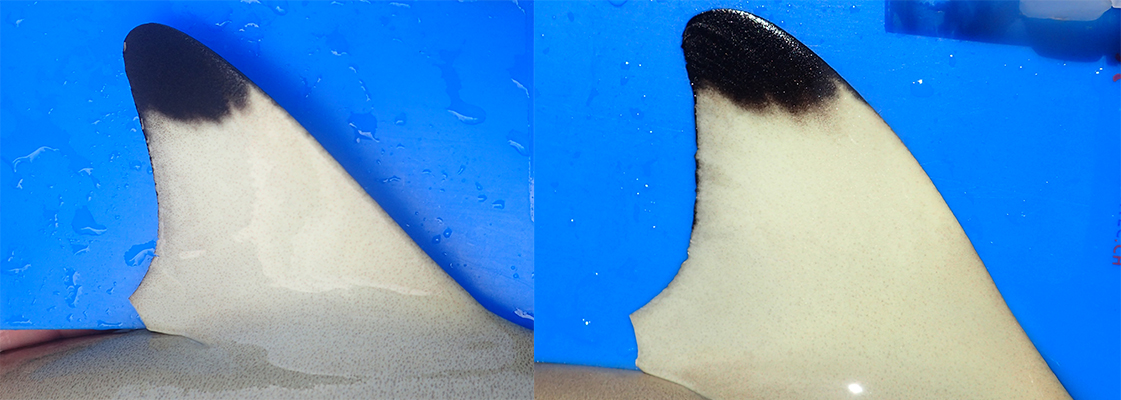

Photo-ID techniques can even be used on sharks with less ornate dorsal fins. Scars, deformities or the shape of the fin can also be used to identify individuals (figure 4). Recent technology that eanbles cameras to be used safely underwater has opened up a new world of possibilities for photo-ID studies.