A place called home

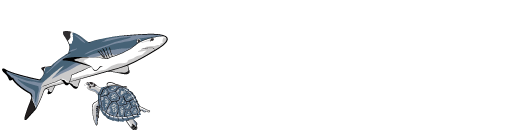

Reef manta rays are highly resident around D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll in Seychelles

“They’re so charismatic,” enthuses Lauren. “I feel that they’re such a good flagship species to get people passionate about the ocean”. A Save our Seas Foundation project leader, and PhD graduate from the University of Western Australia, Lauren Peel has long had an interest in reef manta rays Mobula alfredi. More specifically, “My research interests are focused on elasmobranch (sharks, rays and skates) movement patterns. Why do sharks and rays live in certain places? What drives their movement to-and-from these places? Why do they aggregate in certain locations, at certain times of the year?” But Lauren’s interest is more than just academic; understanding how animals move is an essential part of being able to identify the threats that they face, and how best to protect their populations in key aggregation areas.

Lauren and her colleagues tracked their movement patterns across Seychelles to understand how, and where, reef manta rays are moving. She focused on D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll, and the broader Amirantes Island Group region. Combining data from satellite tags, acoustic tags and the identification of individuals from photographs (photo ID), her worked has shown that the reef manta rays from D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll were mostly resident to the Amirantes Island Group. D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll appear to be key habitats, from which reef manta rays seldom ventured far. Lauren and her colleagues published the results from her latest study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science on 10 July 2020. Her findings add to the previously scant information about where reef mantas move in the Western Indian Ocean, and her methodologies form the basis of information that may be valuable to other researchers elsewhere in the world tracking marine megafauna. “We had suspected that D’Arros Island was an important site to reef manta rays because we routinely recognised individuals that returned to the island. We could identify them from photographs, and people were notifying us of repeat visits by individuals they had come to recognise. However, we had no idea of the sheer significance of the site, and certainly not of how their movements related to the broader Seychelles Archipelago”.

Reef manta rays and the Seychelles Manta Project

Reef manta rays belong to the group of cartilaginous fishes called elasmobranchs (sharks, rays and skates). They are listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on their Red List of Threatened Species, and on Appendix II of the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species. The IUCN Red List gives us a barometer of a species’ population health, and a Vulnerable status highlights that there are declines in reef manta ray populations around the world. They are targeted in fisheries for their highly-valued gill plates (paper-thin filaments used to filter food from the water), caught as bycatch (incidental catch) in other fisheries, and are often victims of boat strike injuries or death. The demand for manta gill plates in the market for traditional Asian medicine prompted the CITES listing of all species of mobula rays (manta and devil rays), because this trade threatens their survival.

The increasingly troubling status of manta rays around the world is dismaying for Lauren, but also adds a conservation imperative that underscores the value of her work in Seychelles: “Reef manta ray populations are severely threatened by all these pressures in other places. They are slow-growing and have low reproductive rates, which makes it harder for their populations to recover from declines. When a female gives birth every two or three years, she may have only one pup – or perhaps a maximum of two”. Lauren’s work at the Save our Seas Foundation (SOSF) D’Arros Research Centre formed part of the Seychelles Manta Ray Project, which in turn is part of a global movement to better understanding the biology and ecology of manta and devil rays. “There is no formal protection for the species in Seychelles. It’s something that we are slowly working towards, but in the interim, the species is still under potential threat from fisheries and boat strikes. We would expect the recently designated zone 1 MPA around D’Arros Island and larger zone 2 that includes St. Joseph Atoll to be beneficial to the reef manta ray population”. Understanding more about reef manta rays in Seychelles is important because the region might represent some of the best protection for rays that occasionally visit other aggregation sites in the broader Western Indian Ocean.

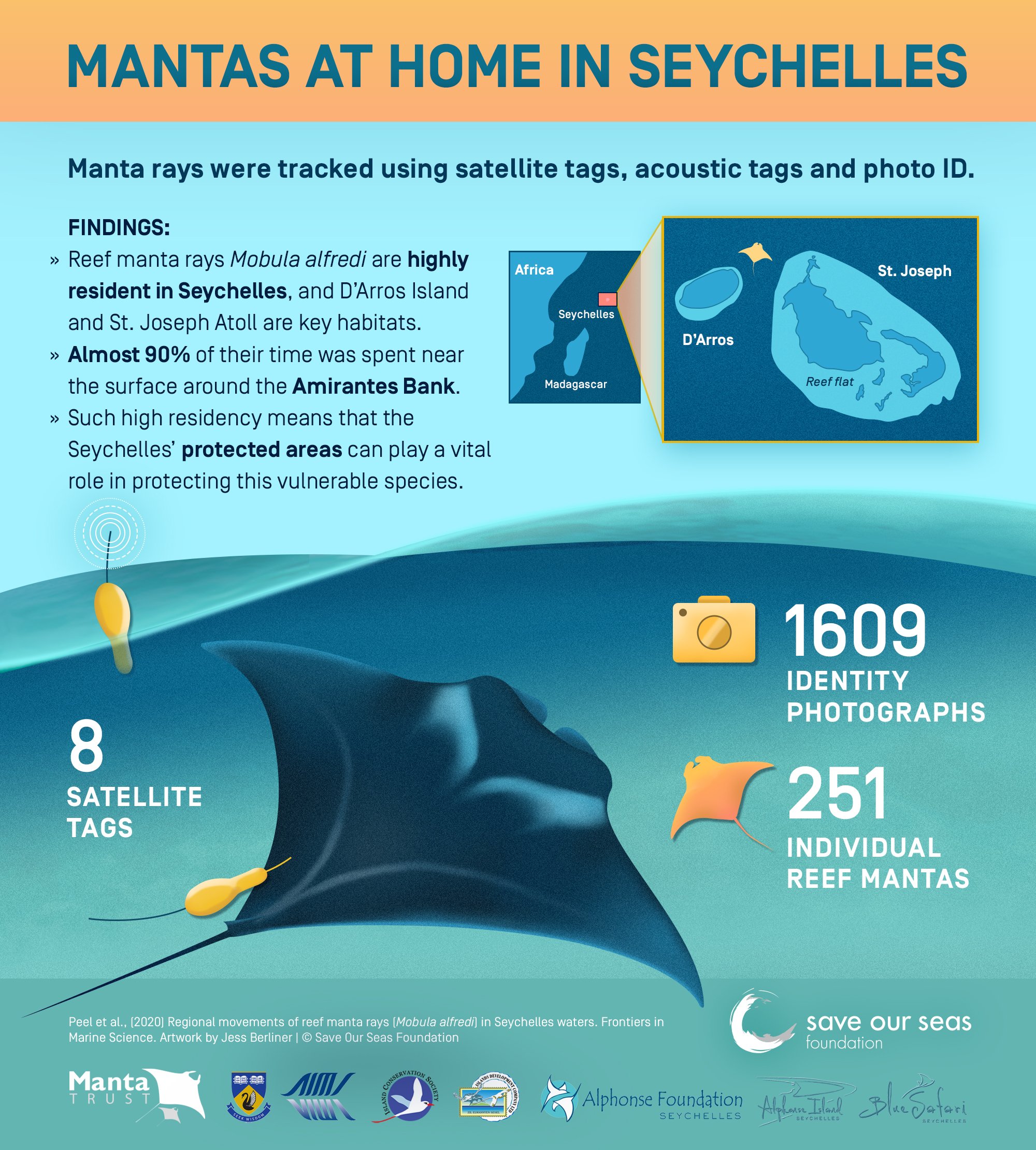

A manta ray at a cleaning station at D’Arros moments after being tagged. Photo © Guy Stevens | Manta Trust

How the science works in the field

Lauren and her colleagues used three different methods to paint a holistic picture of where reef manta rays were moving in Seychelles. Eight manta rays were tagged with pop-up archival tags (which are also programmed to log light, temperature and depth data for a predetermined period of time). The tag is scheduled to “pop-up” or release from the animal, and the archived data are transmitted via satellite or downloaded when the tag is retrieved. It’s a powerful way to get very detailed information about both the large- and small-scale movement patterns of animals. “But satellite tags only give you a snapshot in time – they don’t last forever”, notes Lauren. “I’m a huge believer in the power of multi-faceted approaches to research questions. If you can use multiple techniques, it’s a great way not only to cross-reference your results against one another, but also to safeguard against one technique not working!”.

The researchers also used records of acoustically-tagged animals to gather information about reef manta movement patterns. Acoustic tags are more affordable than satellite tags, which means a great deal more of them can often be deployed (which means more data from more animals, and over a longer timeframe). Acoustic telemetry works because the tag on the animal transmits a uniquely coded signal that is detected whenever a tagged animal swims within the detection radius of receivers deployed at the study site. However, this means that picking up on manta ray movements is restricted to the spatial extent of the receiver array that is deployed to detect tagged animals.

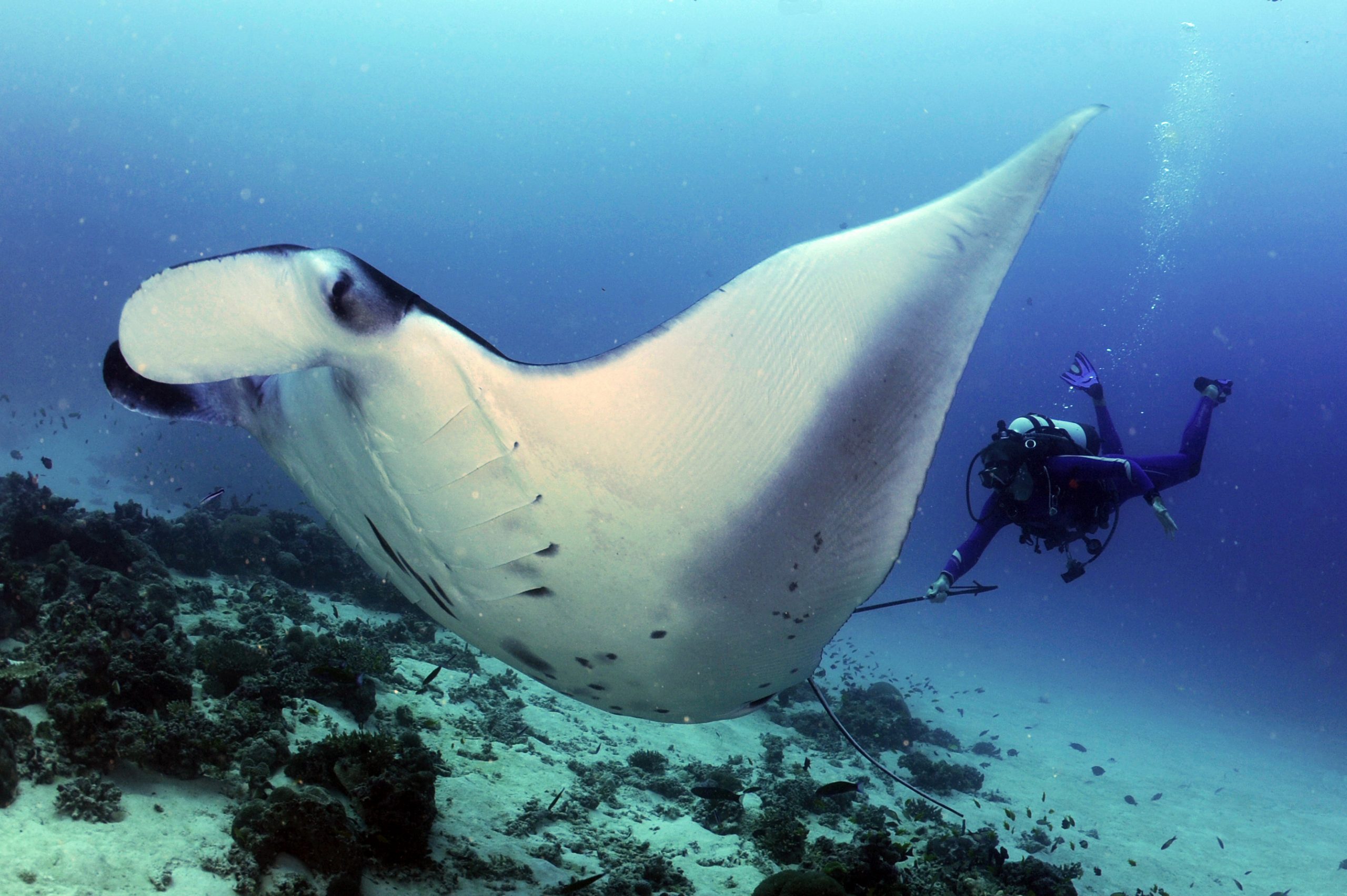

Reef Manta Ray & photographer taking photos for photo identification at D’Arros Island, Seychelles. Photo © Guy Stevens | Manta Trust

Finally, Lauren also used photo-identification to understand movement and site fidelity. This means that the unique and permanent markings on photographed reef manta individuals were logged, and all photos stored in a database that could be compared against over time. Repeat visits of reef mantas to specific sites could be added to the database and compared to previous photographs to build a reference of which known individuals were repeatedly using sites, and the frequency of their returns. Reef manta sightings were recorded opportunistically throughout Seychelles by the researchers, their collaborators, and the public from 2006 to 2019. Lauren also conducted three dedicated manta surveys at D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll in 2013, 2016 and 2017. A dedicated manta survey was also completed at Alphonse Atoll and St. François Atoll in 2017, in collaboration with the Island Conservation Society, Islands Development Company, Alphonse Island Limited, Blue Safari Seychelles and the Alphonse Foundation. Lastly, a remote camera system was deployed at a manta ray cleaning station to the north of D’Arros Island in 2017 to continuously monitor reef manta ray visits over a three-month period.

“One of the aspects of this study that I’m most passionate about, aside from what we’ve been able to learn about the mantas, is that it forms the basis of an important foundation for future research in Seychelles. The study, therefore, doubles as both a key source of information for policymakers, and a guide for future researchers to help determine which methods are most appropriate and logistically-viable to answer their research questions”.

A manta breaks the water’s surface, the trees of D’Arros island can be seen in the background. Photo © Dan Beecham

High residency for reef manta rays at D’Arros Island

Lauren is buoyant about the results, and how they are a first step towards piecing together a complex puzzle of movement patterns right across Seychelles and the Western Indian Ocean: “It was really good to see that the results from all of these different data streams that we were collecting through the Seychelles Manta Ray Project – whether it was photo ID (seeing the same individuals at the same islands), or acoustic telemetry (showing that the mantas weren’t leaving the Amirantes Island Group) or the satellite tags (giving us the potential to detect these large-scale movements, but confirming that they weren’t really happening) – reinforcing the findings from every individual method, and collectively giving us a strong statement; D’Arros Island is very important to these animals”.

She found that reef manta rays from D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll are highly resident, and that only three individuals to-date have been confirmed to travel the 200 km journey south to visit the neighbouring St. François Atoll. It seems, then, that the recently declared zone 1 MPA around D’Arros Island may well protect reef manta rays that spend most of their time in this area. In particular, the study confirms that even large animals like manta rays can have restricted movement patterns, sticking closely to a preferred area. Reef manta rays tracked with satellite tags from D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll spent up to 87% of their time in the upper water column close to the Amirantes Bank. This is crucial information, as the rays may face increasing future threats from fisheries in unprotected waters. The results highlight the fact that suitably regulated tourism and fishing activities on the Amirantes Bank could benefit conservation efforts for the whole Seychelles region, and that potential extension of protected areas in the Amirantes Bank might be beneficial to reef manta ray populations.

Manta’s swimming just off the shore of D’Arros Island. The cleaning station at the coral reef is frequently visited by the manta rays. Photo © Dan Beecham

Interestingly, none of the satellite-tagged individuals left Seychelles’ territorial waters. “We learn more each time we get a new tag out”, explains Lauren. “We had a good understanding that reef manta rays in Seychelles’ territorial waters weren’t travelling huge distances, but it was incredible to really get evidence that this is happening at a remote archipelago, and that reef manta rays are staying around these island chains. It’s always possible that they do occasionally travel large distances, and in those instances, it’s about how many tags you can deploy to increase your chance of detecting those movements. But even elsewhere around the world, we’ve yet to see a really long journey undertaken for these mantas.” Seychelles might be uniquely placed, therefore, to protect reef manta rays that may occasionally visit other aggregation sites in the broader Western Indian Ocean, where they may face increased fishing pressures.

The role of reef manta rays in coral reef ecosystems

As much as the results from Lauren’s work are about the importance of D’Arros Island to reef manta rays, they are also about what reef manta rays mean for D’Arros Island. Her previous work has shown that reef manta rays bring important nutrients to the shallow coral reefs around D’Arros Island, from their night-time feeding grounds in deeper water further offshore. Her work has shown that reef manta rays play a key role in the complex food web around D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll. By inference, these rays are part of maintaining a healthy, functioning coral reef system in Seychelles.

Reef manta in the waters surrounding D’Arros Island. Photo © Dan Beecham

At the same time, other work emerging from the SOSF-DRC has shown that the near-pristine and remote ecosystems around these islands are protected from pollution, overfishing and coastal development: stressors that would otherwise reduce the coral reefs’ capacity to adapt to a changing climate and recover from coral bleaching events . In fact, it appears that the stable fish populations and limited human disturbance in this region might help bleached corals recover better than those reefs that were battered by the devastating bleaching event of 2016 and 2017. “You need an MPA to protect the species”, Lauren muses – “but you also need the manta rays for the MPA to effectively do its job”.

“I think that this has been an important first step, to get the first satellite tracks from these mantas. And visualising how their movement patterns are related to the Island Groups. Reinforcing not only our understanding of how the mantas are using D’Arros, but to get a feel for the scale of movement that we’re looking at. To get an idea of whether small MPAs around key islands are sufficient, or whether we need to investigate protection across the whole Amirantes Bank.”

Looking to the future

D’Arros Island and St. Joseph Atoll represent a remote refuge, a near pristine vestige of blue wilderness in Seychelles where so much can be learned about – and from – the reef manta ray populations that reside there.

“There is an opportunity here, to learn more about these animals in a remote part of the world, where their movements still reflect what we cannot see from other areas where the impact of human-beings is higher.”

The markings on the underbelly of manta rays are unique to each individual. These markings assist researchers in identifying individuals and monitoring their movements, as well as monitoring the number of individuals found in certain regions. Photo © Dan Beecham

Prompted for where the future of manta research is headed in Seychelles, Lauren’s contemplative tone switches quickly back to the enthusiasm that launched our interview: “We do have photo ID records of manta rays from the majority of the Island Groups of Seychelles, confirming that there are manta sightings throughout this precious archipelago. It’s the incentive – and scientific evidence – that we need to motivate as to why we need to keep going! What we’ve been able to achieve in this study at D’Arros Island, and across the Amirantes, give us a strong idea of what potential there is to extend this level of research across Seychelles. Our results even point to a logical next research step to prioritize: extending efforts to include the nearby St. François Atoll where we have photo ID data that shows repeat visits to the Atoll (a possible indicator of site fidelity), and have confirmed the connection of three individuals to this location from D’Arros Island”.

A first step, perhaps, but judging from the combination of Lauren’s determination and the level of insights we continue to gain about the lives of reef manta rays and what they mean to us, certainly not the last.

Reference: Peel LR, Stevens GM, Daly R, Keating Daly CA, Collin SP, Nogués J, Meekan MG (2020) Regional movements of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in Seychelles waters. Frontiers in Marine Science.

Read the publication here.