Whole mitochondrial genomes: the next frontier for great hammerhead shark conservation genetics

The great hammerhead shark is the largest of the 10 species in the hammerhead family and an incredible animal. The first time I had the privilege to encounter a great hammerhead was during a local shark-tagging trip with the Guy Harvey Research Institute. As we were pulling in our line, we saw a massive, sickle-like dorsal fin break the surface and knew we were in for a treat. Thankfully, the shark was worked up quickly and swam away from the boat in good health, off to search the shallows using its highly developed cephalofoil (head) and sense of smell for its next meal.

I mention the quick release of the shark because the large hammerhead shark species (great, scalloped and smooth) are particularly sensitive to the stress of being caught. These sharks have a high post-release mortality rate, which does not bode well for the fate of hammerhead sharks taken as by-catch in commercial fisheries. Not only do great hammerheads have a high mortality rate, but their fins are also highly valued in the international fin market. Because of these pressures, the great hammerhead has suffered declines in abundance throughout its global range and is currently assessed as globally Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

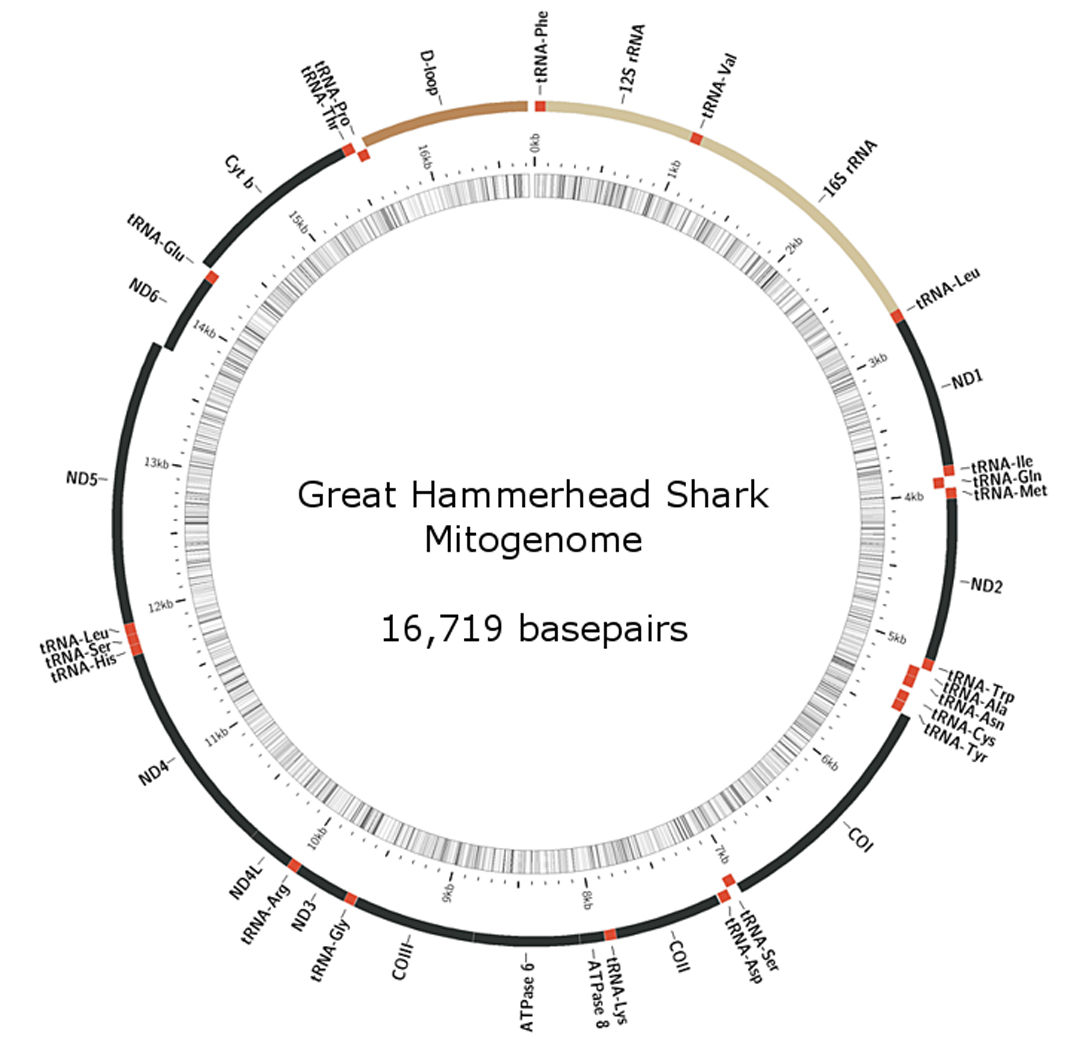

A graphic representation of the complete mitochondrial genome of the great hammerhead shark, generated by MitoAnnotator by MitoFish (Iwasaki et al. 2013).

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, genetic studies offer a powerful tool to learn about the biology and stock structure of shark species. Classic population genetic studies relied on sequencing a relatively small portion of the genome (the complete set of genetic material), usually of the mitochondrial genome (the genetic material contained in a circular DNA molecule inside each cell’s mitochondria). With rapid advancements in sequencing technology in recent years, however, conservation geneticists have new opportunities to explore the genetics of the creatures we study at a larger scale and with a higher-resolution view of population dynamics.

As part of my PhD research, I sequenced the first complete mitochondrial genome of the great hammerhead shark (the paper can be found here). This sequencing effort provides a genomic resource for future investigations into great hammerhead population dynamics. Sequencing a whole mitochondrial genome instead of small portions of it will enable researchers to gain a much more in-depth look into the evolutionary history of these animals, ultimately contributing to our understanding of this species and our ability to properly manage and conserve it.